الانتشار البحري الأمريكي في الكاريبي 2025

| الانتشار البحري الأمريكي في الكاريبي 2025 | |

|---|---|

| جزء من فترة ما بعد الحرب الباردة، الحرب على الكارتيلات، تبعات الحرب على الإرهاب، حرب المخدرات المكسيكية، والأزمة في ڤنزويلا | |

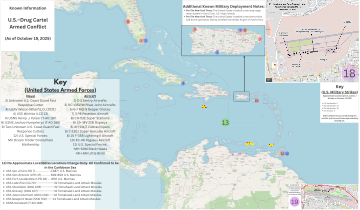

خريطة توضح النزاع، بما في ذلك المواقع التقريبية للقوات الأمريكية والمواقع التقريبية للغارات الجوية. | |

| الموقع | |

| التخطيط | |

| الهدف | مكافحة تهريب المخدرات |

| التاريخ | أغسطس 2025 – الحاضر |

| التنفيذ | |

| الخسائر | اعتباراً من 24 أكتوبر 2025، في بحر الكاريبي فقط، 38[2][3] قتيل |

في أواخر أغسطس 2025، بدأت الولايات المتحدة تعزيز قواتها البحرية في جنوب بحر الكاريبي بهدف معلن هو مكافحة تهريب المخدرات.[4][5] أصدر الرئيس الأمريكي دونالد ترمپ توجيهاته إلى القوات المسلحة الأمريكية للبدء في استخدام القوة العسكرية ضد بعض كارتلات المخدرات في أمريكا اللاتينية، ووصف المهربين بأنهم إرهابيو المخدرات.[6][7]

كانت العملية الأولى للحملة هي هجوم 2 سبتمبر على سفينة قادمة من ڤنزويلا ويزعم أنها تضم أعضاء عصابة قطار أراگوا الذين يحملون مخدرات غير مشروعة، مما أسفر عن مقتل 11 شخصاً.[8][9] نشرت الولايات المتحدة أصولاً عسكرية في پورتوريكو، ودمرت الغارات الجوية اللاحقة سفناً أخرى مزعومة لتهريب المخدرات، بما في ذلك تلك المرتبطة بجيش التحرير الوطني، وشاركت البحرية الدومينيكانية في استعادة المخدرات من إحدى السفن المدمرة.

وقال خبراء ومصادر في إدارة ترمپ والمعارضة الڤنزويلية إن الهدف المحتمل للعملية هو إجبار كبار الشخصيات في حكومة نيكولاس مادورو على الرحيل؛[10][11][12][13][14] وتكهن آخرون بأن غزو ڤنزويلا غير محتمل،[15][16][17] وتساءلوا عن مدى قانونية الضربات التي تتعرض لها السفن.

خلفية

The militarization of the war on drugs—also known as the war on cartels—dates to 1989 during the presidency of George H.W. Bush, when Bush introduced a national drug control strategy that emphasized supply interdiction and allocated significant resources to involve the Department of Defense. This included the creation of the Office of National Drug Control Policy and formalized the use of military forces in detection operations, foreign force training, and support for law enforcement agencies.[18] On 18 September 1989, then-Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney announced specific plans: a Caribbean counternarcotics task force with military aircraft and ships, deployment of forces along the Mexican border, expanded use of the North American Aerospace Defense Command to detect drug trafficking, and training of forces in South American countries such as Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia. Cheney emphasized that the military would not conduct arrests or raids but would expand its role in detection and logistical support, involving "a few hundred" troops in Latin America.[19][20]

In 1989, president Bush ordered the invasion of Panama to depose the country's de facto dictator, Manuel Noriega. The invasion was condemned by the United Nations General Assembly as a "flagrant violation of international law". The US later provided intelligence about flights with civilians suspected of carrying drugs to Colombian and Peruvian officials; after several planes were shot down, the Clinton administration ceased its assistance in providing information. The United States Navy has intercepted ships believed to be used for drug smuggling operations. The United States Armed Forces broadly engage in joint anti-drug training exercises with other countries, including Colombia and Mexico.[21]

During the presidency of George W. Bush, the AUMF Act and the Specially Designated Global Terrorist designation in the context of the war on terror laid the groundwork for subsequent classifications.[22]

الإجراءات الأولية

In January 2025, US President Donald Trump signed Executive Order 14157 that directed the US State Department to label certain Western Hemisphere drug cartels as Foreign Terrorist Organizations and Specially Designated Global Terrorists.[21][23] In February, the Trump administration designated Tren de Aragua, a criminal organization from Venezuela; MS-13; and six Mexico-based groups as foreign terrorist organizations,[24] saying at the time they posed "a national-security threat beyond that posed by traditional organized crime."[21] In July, the US designated the Cartel of the Suns (Cartel de los Soles), a purported criminal organization that the US alleges has ties to Venezuelan leadership, as a terrorist organization.[25][5] At the time, the US State Department's Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs posted on X that it would use "all the resources at our disposal to prevent Maduro from continuing to profit from destroying American lives and destabilizing our hemisphere."[25] US intelligence assessments have contradicted claims made by the Trump administration in legal filings that Maduro controls Tren de Aragua.[26] The Trump administration asked for the assessment to be repeated, and it reached the same conclusion.[26]

Donald Trump's decision to designate drug cartels as "terrorist" organizations—including the Sinaloa Cartel, the Jalisco New Generation Cartel, Cártel del Noreste, Tren de Aragua, MS-13, the Gulf Cartel, and La Nueva Familia Michoacana Organization[27]—established the foundation for US intervention.[28] In July,[29] Trump secretly signed an executive order directing the armed forces to invoke military action against cartels that had been declared as terrorist organizations.[21]

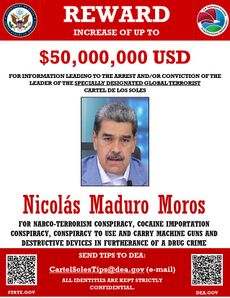

The Trump administration has accused President of Venezuela Nicolás Maduro of trafficking drugs into the US. Earlier in August, the Trump administration raised to $50 million a bounty for the arrest of Maduro over what it alleges to be his role in drug trafficking. Maduro was indicted in the US on drug charges including narcoterrorism in 2020.[24]

After authorizing the Pentagon to use military force against Latin American drug cartels,[29] the Trump administration doubled the reward for the capture of Maduro to $50 million.[30] At the time, an anonymous US official told Reuters that military action against those groups did not seem imminent; another official told Reuters that powers granted in the order included allowing the Navy to carry out sea operations including drug interdiction and targeted military raids.[31]

In August 2025, the US began deploying warships and personnel to the Caribbean, citing the need to combat drug cartels,[32][33] although most of the fentanyl entering the US is over land via Mexico.[5] On 20 August, Trump ordered three Navy warships to the coast of South America.[34][35] As of 29 August, seven US warships, along with one nuclear-powered fast attack submarine, were in and around the Southern Caribbean, bringing along more than 4,500 sailors and marines.[36]

The Central Intelligence Agency joined the military campaign after confirming that it would play a significant role in combating drug cartels, just as it is considering using lethal force against these criminal organizations.[37]

Venezuela said it would mobilize more than four million soldiers in the Bolivarian Militia of Venezuela.[38] On 26 August, Venezuela's defense minister announced a naval deployment around Venezuela's main oil hub.[4] Maduro said he "would constitutionally declare a republic in arms" if the country is attacked by forces that the US has deployed to the Caribbean.[39][40]

الانتشار الأولي والغارات الجوية

According to The Economist, the US typically has "two or three American warships and Coast Guard cutters" on patrol in the southern Caribbean.[5] As of 25 September, the deployment includes ten ships: the guided-missile destroyers يوإسإس Gravely, يوإسإس Jason Dunham, and يوإسإس Sampson; the amphibious assault ship يوإسإس Iwo Jima and the amphibious transport docks يوإسإس San Antonio and يوإسإس Fort Lauderdale; the guided-missile cruiser يوإسإس Lake Erie; the littoral combat ship يوإسإس Minneapolis-Saint Paul;[41] the nuclear fast attack submarine يوإسإس Newport News,[4] the special operations ship MV Ocean Trader[42] and the missile destroyer يوإسإس Stockdale.[43] According to the Financial Times, "Five of the eight vessels are equipped with Tomahawk missiles, which can hit land targets."[4]

The Iwo Jima, Fort Lauderdale, and San Antonio of the Iwo Jima Amphibious Ready Group left Norfolk, Virginia on 14 August,[44] with more than 4,000 personnel, including the 22nd Marine Expeditionary Unit, with 2,200 Marines.[أ] According to the US Naval Institute this marked "the first time a US-based Amphibious Ready Group with embarked Marines has deployed since December."[44] Historian Alan McPherson stated that the naval buildup is the largest in the region since 1965.[12] It has been the largest anti-drug military campaign since the US invasion of Panama.[بحاجة لمصدر]

During a surprise trip on 8 September to Puerto Rico with US Joint Chiefs of Staff, Dan Caine, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth told sailors and Marines assigned to the area: "What you're doing right now – it's not training ... This is the real-world exercise on behalf of the vital national interests of the United States of America to end the poisoning of the American people."[47]

In response to the presence of Navy warships in Latin America, two Venezuelan BMA F-16 fighter jets flew over the USS Jason Dunham on 4 September.[48] The US Department of Defense called it "highly provocative" and deployed ten F-35 fighter jets[49] and two MQ-9 Reaper drones[50] to Puerto Rico.[51] That same day Rubio met with Ecuadorian president Daniel Naboa in Quito; Rubio stated that Trump intended to "wage war" on those that have "been waging war on us for 30 years" and designated the gangs Los Lobos and Los Choneros as narco terrorists, in agreement with Noboa.[52][53] Later on 23 September, the United States added the 18th Street gang to the designated foreign terrorists list, which is largely based in the Caribbean coastal nations of Guatemala and Honduras among others.[54]

The Venezuelan government stated on 12 September that a US destroyer had detained and boarded a tuna fishing boat with nine crew members. The destroyer eventually released the boat, and it was escorted away by the Venezuelan navy. Venezuelan Minister of Foreign Affairs Yván Gil responded that this act was illegal and added that Venezuela would defend itself.[55]

In a display of its military strength, Venezuela initiated large-scale military exercises in the Caribbean on 17 September. The maneuvers, involving naval and air forces, were intended to bolster the nation's defense capabilities and demonstrate its readiness to protect its sovereign waters.[56]

On 25 September, Task & Purpose reported that the US had deployed special operations ship MV Ocean Trader to the Caribbean.[42]

الغارات الجوية على السفن

On 2 September, Trump said that the US had struck a boat carrying unspecified illegal drugs, alleging it was operated by the Tren de Aragua. Trump said that the strike killed 11 "narcoterrorists".[9] According to The Wall Street Journal, "The attack was the US military's first publicly acknowledged airstrike in Central or South America since the US invasion of Panama in 1989."[57] Trump hinted at further military action, stating: "There's more where that came from."[9][58]

The following day, Hegseth stated that military actions against cartels in Venezuela would continue.[59] Secretary of state Marco Rubio, speaking in Mexico City, said that further strikes would occur, adding that the US was aware of the identities of those on the destroyed boat, but did not provide evidence to authenticate their identity as Tren de Aragua members.[60]

Trump announced on 15 September that another Venezuelan boat had been struck that morning, killing three people who were, according to him, "confirmed narco-terrorists". No evidence that the vessel was carrying drugs was provided.[61][62] The Guardian reported in September that anonymous sources said that a "leading role" was taken in the decision to strike the boats by the newly empowered Homeland Security Council under its leader Stephen Miller, with many White House officials learning about the second strike just hours before it happened.[63] On 16 September, Trump stated that the US military had sunk an alleged drug-running boat.[64]

Trump announced on 19 September that another vessel allegedly carrying drugs had been destroyed in the Caribbean and that three men had been killed; Trump stated that the vessel was "affiliated with a Designated Terrorist Organization conducting narcotrafficking in the USSOUTHCOM area of responsibility".[65][66] The Dominican Republic later announced that it had cooperated with the US Navy in a first-ever joint operation to locate the boat and salvage 377 packages of cocaine.[67]

On 3 October, Hegseth announced that a strike on a vessel near the coast of Venezuela killed four,[68][69][70] and two US officials later declared without approval that there were Colombians on at least one of the boats.[71] Trump posted a statement on Truth Social on 14 October that six more were killed in a strike near the coast of Venezuela.[72]

Reuters reported that another previously unannounced strike on 16 October had killed two and, for the first time, included two survivors who were being held on a Navy ship.[73][74] By 19 October, both were repatriated to their respective countries of origin, Colombia and Ecuador.[75][76][77]

On 17 October, three were killed in a strike on an alleged drug vessel operated by the Colombian National Liberation Army (ELN);[2][78][79] the ELN denied involvement in any drug boat trafficking.[80] On 24 October, Hegseth announced "the first strike at night" occurred, against an alleged drug vessel operated by Tren de Aragua in the Caribbean, killing six people on board.[81][3]

إعلان النزاع المسلح والتصعيد

On 30 September, Trump told reporters his administration would "look very seriously at cartels coming by land", which according to the Miami Herald "align[s] with recent media reports suggesting the administration is reviewing plans for targeted operations inside Venezuela."[82]

Trump formally declared to Congress on 1 October that the US was in a "non-international armed conflict" with "unlawful combatants" regarding drug cartels operating in the Caribbean.[83][84] The Guardian stated that the memo to Congress referred to the cartels as "non-state armed groups" engaged in attacking the US.[85][86] Andrew C. McCarthy stated in the National Review that this terminology refers to a conflict "that does not pit two sovereign nations against each other"[87] and means "armed hostilities conducted by a subnational entity that is not acting on behalf of a foreign sovereign", giving the example of Al-Qaeda and the attacks of 11 September.[88] The Miami Herald wrote that: "In an armed conflict, a country can lawfully kill enemy fighters even when they pose no threat."[89] The Washington Post stated: "Some lawmakers and experts have said the notification is a dubious legal justification for what have been unlawful military strikes on alleged civilian criminals".[90]

Vladimir Padrino López, Venezuela's Minister of Defense, stated on 2 October that five US "combat planes" had been detected flying near Venezuela at 35،000 أقدام (11،000 m) altitude, which he called a "provocation"; a government statement said the plane was 75 كيلومتر (47 mi) from the Venezuelan coast, which CNN states is outside of Venezuelan territory.[91]

As of 8 October, the number of US troops in the Southern Caribbean and Puerto Rico had expanded to 10,000;[92] US military assets in the region are insufficient for an invasion.[93][15][16] The forces included elements of the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment which provides helicopter aviation support for special operations forces.[94] Venezuela's armed forces are estimated at 125,000 as of October 2025, with experts saying its military is "in shambles" according to The Wall Street Journal, which wrote on 17 October that Venezuela had issued a call to arms, and "cranked up its propaganda machine", announcing that the US wanted its oil wealth, as Venezuela was moving troops to the coast and prepared to "repel any invasion".[94]

الجهود الدبلوماسية

On 6 October, Trump directed special envoy Richard Grenell to shut down all diplomatic talks with Venezuela amid growing tensions and frustrations with Venezuelan political dialogue.[95] Since at least April 2025,[96] Qatar had acted as a political go between, attempting to maintain communications between the two nations through back channel diplomacy.[92]

Sources told the Miami Herald that Qatar, which "has close ties to the Venezuelan government", had "played a key role as intermediary" between Maduro officials and siblings, Delcy and Jorge Rodríguez, in promoting Delcy and the unrelated Miguel Rodríguez Torres to lead a transition as "a 'more acceptable' alternative to Nicolás Maduro's regime", with the aim of "preserving political stability without dismantling the ruling apparatus".[96] The Associated Press confirmed the report,[97] and stated that an anonymous official said the proposal was that Maduro be replaced by Delcy through the end of his term in 2031; the AP reported that Washington "rejected the proposal because it continues to question the legitimacy of Maduro's rule".[98] Maduro and Delcy Rodriguez labeled the information as fake news.[98] Delcy Rodríguez said the report was part of a psychological warfare operation.[97]

نزاع كولومبيا

Following increased criticism by Colombian President Gustavo Petro over US strikes on vessels and support for Israel during his visit to the September session of the UN General Assembly,[99] the US Department of State revoked Petro's visa on 27 September, stating on X that: "Earlier today, Colombian president (Gustavo Petro) stood on a NYC street and urged U.S. soldiers to disobey orders and incite violence."[100]

On 18 October, Petro stated that the 16 September strike announced by Trump had killed a Colombian fisherman;[101] other sources said he was referring to the 15 September strike.[78][79] Petro said the vessel was not involved in drug trafficking, and accused the US of murder.[78] The US labeled the charged "baseless".[102] Trump responded calling Petro an "illegal drug leader", who was "low rated" and not helping diminish production of drugs, stating that the US would end the large subsidies it provided to Colombia.[78][79]

In October 2025, the United States Department of the Treasury announced sanctions against Petro and Interior Minister Armando Benedetti, citing their alleged involvement in illicit drug trafficking activities. These measures marked a significant deterioration in bilateral relations, with the Colombian government condemning the decision as politically motivated and labeling it "an act of aggression" against its sovereignty. Analysts described the move as one of the most severe diplomatic escalations between Bogotá and Washington in recent years.[103]

التوسع

Hegseth announced on 10 September the formation of a new counternarcotics joint task force, to operate in Latin America, the Western hemisphere, and the area of the United States Southern Command (USSOUTHCOM), to be headed by the II Marine Expeditionary Force, intended "to crush the cartels, stop the poison and keep America safe".[104][105] On 15 October, Trump confirmed he had authorized the CIA to conduct lethal ground operations inside Venezuela and elsewhere around the Caribbean, and that military officials were drafting options for strikes on Venezuelan territory.[26] The New York Times reported the next day that Alvin Holsey would retire as head of USSOUTHCOM, with anonymous sources reporting tension between Holsey and the Trump administration over Venezuela.[106]

The US Air Force participated amid the campaign on 15 October 2025 when airmen flew B-52 Stratofortress ("a long-range, heavy bomber that can carry precision-guided ordnance or nuclear weapons") north of Caracas for two hours, joining F-35B Lightning II from the Marines, in a "bomber attack demonstration mission", according to Task & Purpose.[107] On 23 October, at least two US Air Force B-1B Lancers from Dyess Air Force Base, supported by KC-135 tankers from MacDill Air Force Base and an unknown type variant of RC-135 reconnaissance aircraft, conducted a flyby reportedly within 50 miles of the Venezuelan mainland.[108][109] When asked at a press conference about the B-1 flyby, Trump denied that the event had occurred.[108] Also on 23 October, an Air Force E-11A Battlefield Airborne Communications Node (BACN) aircraft was observed operating near Puerto Rico.[108]

Trump said on 22 October that he planned to also order strikes on land targets.[110] Government officials from Trinidad and Tobago stated that the Gravely destroyer would spend four days there at the end of October, and their country's forces would jointly train with US Marines.[111]

Hegseth ordered the supercarrier يوإسإس Gerald R. Ford deployed to Latin America on 24 October.[111] According to The Washington Post, it is "the world’s largest aircraft carrier, typically carrying dozens of fighter jets, numerous helicopters and more than 4,000 sailors", and its deployment "signaled a major expansion of [the] military campaign against 'Transnational Criminal Organizations' in Latin America".[111] CNN and the Wall Street Journal wrote that the deployment of Carrier Strike Group 12 and Gerald R. Ford would be to the Caribbean;[112][113] The Washington Post and the New York Times wrote that where in Latin America the warship would be positioned, within the Southern Command, was unknown.[111][114] The Ford's full air wing is reportedly embarked.[115] Though her escort typically includes four Arleigh Burke class destroyers—USS Winston S. Churchill, USS Bainbridge, USS Mahan, and USS Forrest Sherman—as of 20 October some of her escorts including the USS Forrest Sherman were still operating independently in other areas of the globe (such as the Red Sea).[115]

ردود الفعل

ڤنزويلا

On 18 August, Maduro said the US "has gone mad and has renewed its threats to Venezuela's peace and tranquility".[24] He "announced the planned deployment of more than 4.5 million militia members" around Venezuela, per The Associated Press,[24] and started militia enrollment on 23 August. The Economist was skeptical of the announcement, stating, "Election receipts show he received fewer than 3.8m votes last year; it is improbable that more people would fight to defend him than would vote for him."[5] The International Institute for Strategic Studies estimated the militia had 343,000 members as of 2020.[38] The BBC reported that many of the recently mobilized militia are "mostly made up of volunteers from poor communities, although public sector workers have reported being pressured into joining them as well."[15] On 25 August, Maduro "said 15,000 'well armed and trained' men had been deployed to states near the Colombian border," per The Economist.[5]

Following the 2 September strike, Maduro said that the US was "coming for Venezuela's riches".[116] Maduro stated that "Venezuela is confronting the biggest threat that has been seen on our continent in the last 100 years".[39]

Venezuelan opposition leader María Corina Machado said the deployment encouraged "tens and tens of thousands" of Venezuelans to join an underground movement aiming to overthrow Maduro. Machado said that the 2024 Venezuelan presidential election gave a mandate for regime change, though said that regime change was the responsibility of Venezuelans rather than of the US.[117] On 15 October 2025 following the destruction of another vessel by American forces, Maduro declared new military exercises in Caracas shantytowns and nearby states.[118]

أمريكا اللاتينية والكاريبي

Gustavo Petro, President of Colombia, initially suggested that any attack on Venezuela would equal an attack on Latin America and the Caribbean, and thus Colombia's armed forces could support Venezuela; he later moderated his position.[4] On 23 September, he addressed the UN General Assembly to call for a "criminal process" to be opened against Donald Trump for US strikes in the Caribbean.[119]

Colombia convened an extraordinary virtual meeting of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States in September 2025, which concluded with an expression of "deep concern" over foreign intervention in the region.[120][121] Over Guatemala's objection that procedures were not followed, the group issued a statement saying the region must remain a "Zone of Peace" based on "... the prohibition of the threat or use of force, the peaceful settlement of disputes, the promotion of dialogue and multilateralism, unrestricted respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, non-interference in the internal affairs of States, and the inalienable right of peoples to self-determination."[120] Guatemala's president Bernardo Arévalo said Guatemala was included in the list of 21 countries (of the 33 members) approving the text, although it did not sign, nor did Ecuador, Peru, Costa Rica, and El Salvador.[122]

In August, when the initial three ships were deployed, Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago Kamla Persad-Bissessar offered the US military access to the Trinidad nation for the US to protect Guyana amid the Guyana–Venezuela crisis.[123][124] Maduro responded that Bisessar's offer was tantamount to declaring war on Venezuela, and threatened both countries with retaliation if Trinidad went through with its offer.[123][125] Bisessar later praised the deployment and the 2 September strike, saying "the US military should kill [all drug traffickers] violently." Foreign Minister of Barbados Kerrie Symmonds said that foreign ministers in CARICOM wrote to US Secretary of State Marco Rubio asking that military operations in the Caribbean not be conducted without prior notice or explanation.[126] The deployment was endorsed by the government of Guyana, two-thirds of its territory being claimed by Venezuela, with Guyana's vice president and former president Bharrat Jagdeo telling The Financial Times "You cannot trust Maduro."[4] According to Havana Times, the deployment "reignited tensions and divided positions in the region", with "the Cuba–Venezuela–Nicaragua axis" calling it an "imperialist offensive", and other countries "harden[ing] their stance against Maduro and the Cartel of the Soles."[127]

The Commander of the Cayman Islands Coast Guard, Robert Scotland, stated that the US strikes would "send a very clear message to those entities who have been designated as narco-terrorists, and should serve as a strong deterrent to anyone who seeks to engage in the illicit trafficking of drugs and firearms within our region". The Office of the Cayman Island's Governor stated that the British government "recognizes the importance of regional security and is committed to providing advice and capacity building to our Cayman law-enforcement partners", highlighted the mutual defense alliance between the British and American governments, and emphasized organized crime as a common threat.[128]

The United States maintains two Forward Operating Locations (FOL) on the Dutch territories of Aruba and Curaçao, stemming from a 2000 treaty.[129] In response to escalating tensions between Venezuela and the US, the Dutch have taken a neutral position, but say treaties must be honored.[130][131][132] Dutch Defense Minister Ruben Brekelmans stated that the treaty "permits flights from Curaçao solely for surveillance, monitoring, and the detection of drug shipments. This consent applies only to unarmed flights". According to the Curacao Chronicle, the minister indicated that the approximate 1,000 soldiers in the Dutch Antilles, as well as the Dutch Caribbean Coast Guard and accompanying aircraft, could be used "if the situation escalates".[133] On 19 September, Prime Minister Gilmar Pisas of Curacao stated it would renew its treaty for the Curacao-based FOL until at least 2 November 2026.[130]

On 9 October, the United States expressed interest in establishing a temporary military radar base on the Island nation of Grenada, at Maurice Bishop International Airport.[134] The Grenadian government under Prime Minister Dickon Mitchell of the center left National Democratic Congress party, responded that it would take the request under review. Critics from the conservative New National Party such as Chester Humphrey and the Independent Peter David urged the Mitchell administration to deny the request, as they feared that the US strikes were a pretext for war with Venezuela, a nation that they say "has not done ... anything" to Grenada.[135][136] The following week Admiral Alvin Holsey traveled to Antigua and Barbuda to make a similar request, but was denied.[137][138] Holsey met with Grenadian officials on 15 October; the meeting had no immediate conclusion. The government—working with CARICOM towards a decision—later stated that decisions would be deferred until "all technical and legal assessments are completed", accounting for national and public interests[139]

تحليل

The Miami Herald reported on 2 October 2025 that sources said the US effort had "effectively shut down" the busy "Caribbean route" for estimated 2024 annual shipments of between 350 and 500 tons of cocaine coming from Venezuela.[140] According to the Miami Herald, the campaign's "goal is financial: cutting off the drug revenue that sustains loyalty among Venezuela's senior military and police commanders, many of whom are accused of profiting directly from narcotrafficking."[140] Trafficking through older air and land routes from Colombia are more costly than maritime shipments, and sources said that Venezuelan "cash flow from trafficking is under direct threat, and that puts the cohesion of the military elite at risk", with "authorities [turning] to heavier taxation and extortion of businesses to keep the state's security apparatus afloat."[140]

According to The Economist, "Few ... think drugs are the sole or even the main focus" of the operation, noting that fentanyl, the drug that causes the most deaths in the US, is almost entirely "synthesized in Mexico and trafficked north over land" and that "the hardware"—e.g destroyers—"doesn't match the task" of drug policing. According to The Economist, "All this makes the most sense if the principal intent is to rattle Mr Maduro, give succour to Venezuela's opposition or even stir an uprising within the Venezuelan armed forces—encouraged perhaps by that recently doubled reward."[5] Experts speaking to Reuters and the BBC described the deployment as gunboat diplomacy[11][12] and Trump administration sources stated a likely goal was to pressure the Maduro administration.[13][14] The New York Times reported that a group of officials, led by US National Security Advisor and Secretary of State Marco Rubio, was pushing for a military campaign that would drive Maduro from power.[141] Members of Venezuela's opposition told the New York Times they have coordinated with the Trump administration on a plan for the first hundred hours after Maduro's deposition.[141][142]

PBS News reported that Trump was using the military to counter cartels he blamed for trafficking fentanyl and other illicit drugs into the US and for fuelling violence in American cities, stating that the government had "not signaled any planned land incursion"[17]—similarly, The Guardian stated that "many experts are skeptical the US is planning a military intervention" in Venezuela.[143]

Experts speaking to the BBC said that the 2 September strike was potentially illegal under international maritime and human rights law. Though the US is not a signatory to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, previous US policy had been to "act in a manner consistent with its provisions"; countries are not supposed to interfere with ships in international waters except in cases such as hot pursuit out of a country's territorial waters.[144][145] Law professor Mary Ellen O'Connell said that the strike "violated fundamental principles of international law". Luke Moffett of Queen's University Belfast, also a law professor, stated that striking the ship without grounds of self-defense could be extrajudicial killing. BBC News argued that "Questions also remain as to whether Trump complied with the War Powers Resolution, which demands that the president 'in every possible instance shall consult with Congress before introducing United States Armed Forces into hostilities'".[144]

According to The New York Times, "specialists in the laws of war and executive power" stated that Trump had "used the military in a way that had no clear legal precedent or basis".[146] Law professor Gabor Rona argued in a 2 October 2025 Lawfare article that, while he agreed with other analysts that the strikes were unlawful, they reflected a predictable overreach that followed the precedents established during the George W. Bush, Barack Obama and Joe Biden administrations following the attacks of 11 September.[147]

Regarding the 2 September strike, Geoffrey Corn, former senior adviser on the law of war to the US Army, said "I don't think there is any way to legitimately characterize a drug ship heading from Venezuela, arguably to Trinidad, as an actual or imminent armed attack against the United States, justifying this military response."[57]

The Financial Times wrote that the strikes were intended to pressure members of the Venezuelan government into resigning or arranging a handover of power by demonstrating the US military's capability to capture or kill them through targeted strikes.[10]

انظر أيضاً

- 2001 Peru Cessna 185 shootdown

- Air Bridge Denial Program

- Joint Interagency Task Force South

- Venezuelan crisis of 1902–1903 – naval blockade by Great Britain, France, Germany, and Italy

الهوامش

- ^ Reuters, "about 4,000 sailors and Marines";[32] Navy Times/Associated Press, "more than 4,000 sailors and Marines";[33] The New York Times, "The Iwo Jima Amphibious Ready Group—including the U.S.S. San Antonio, the U.S.S. Iwo Jima and the U.S.S. Fort Lauderdale, carrying 4,500 sailors—was steaming near Puerto Rico on Friday, Defense Department officials said. So was the 22nd Marine Expeditionary Unit, with 2,200 Marines";[29] The Guardian, "... involves the Iwo Jima amphibious ready group—including the USS San Antonio, the USS Iwo Jima and the USS Fort Lauderdale carrying 4,500 sailors—and the 22nd Marine Expeditionary Unit, with 2,200 marines";[45]Task and Purpose, "... includes about 1,900 sailors with the Iwo Jima Amphibious Ready Group—which consists of assault ship USS Iwo Jima, the amphibious transport docks USS San Antonio and USS Fort Lauderdale — and another 2,200 Marines with the 22nd Marine Expeditionary Unit, who are embarked on the three ships."[46]

المصادر

- ^ Roston, Aram (21 October 2025). "CIA playing 'most important part' in US strikes in the Caribbean, sources say". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 October 2025. Retrieved 21 October 2025.

- ^ أ ب Walsh, Joe (19 October 2025). "Trump administration strikes a seventh alleged drug boat, killing 3, Hegseth says". CBS News. Retrieved 19 October 2025.

- ^ أ ب Marquez, Alexandra; De Luce, Dan (24 October 2025). "U.S. carried out a strike on another alleged drug-carrying boat in the Caribbean Sea, Pete Hegseth says". NBC News. Retrieved 24 October 2025.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Chávez, Steve; Stott, Michael (28 August 2025). "US naval build-up near Venezuela stokes tensions in Latin America". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 29 August 2025. Retrieved 5 September 2025.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ "A surprise U.S. Navy surge in the Caribbean". The Economist. 26 August 2025. Archived from the original on 27 August 2025. Retrieved 5 September 2025.

- ^ "Trump Invokes Post-9/11 Playbook in Attacks on Drug Cartels". The Wall Street Journal. 17 September 2025. Archived from the original on 17 September 2025. Retrieved 17 September 2025.

- ^ Jacobs, Jennifer; Quinn, Melissa (8 August 2025). "Trump tells military to target Latin American drug cartels, source says". CBS News. Archived from the original on 9 August 2025. Retrieved 8 August 2025.

- ^ Stewart, Phil; Ali, Idrees; Holland, Steve (3 September 2025). "US military kills 11 people in strike on alleged drug boat from Venezuela, Trump says". Reuters. Retrieved 3 September 2025.

- ^ أ ب ت Debusmann, Bern (3 September 2025). "Trump says 11 killed in US strike on drug-carrying vessel from Venezuela". BBC News. Archived from the original on 4 September 2025. Retrieved 3 September 2025.

- ^ أ ب Stott, Michael; Politi, James; Daniels, Joe (18 October 2025). "Donald Trump aims to topple Venezuela's leader with military build-up". Financial Times. Retrieved 18 October 2025.

- ^ أ ب Ali, Idrees; Zengerle, Patricia; Shalal, Andrea (1 September 2025). "US builds up forces in Caribbean as officials, experts, ask why". Reuters. Retrieved 9 September 2025.

David Smilde, a Venezuela expert at Tulane University, said the military moves appeared to be an effort to pressure the Maduro government. 'I think what they are trying to do is put maximum pressure, real military pressure, on the regime to see if they can get it to break ... It's gunboat diplomacy. It's old-fashioned tactics'

- ^ أ ب ت Lissardy, Gerardo; Wilson, Caitlin (4 September 2025). "What is Trump's goal as US bombs 'Venezuela drugs boat' and deploys warships?". BBC. Retrieved 9 September 2025.

- ^ أ ب Kube, Courtney; Gutierrez, Gabe; Doyle, Katherine (27 September 2025). "U.S. preparing options for military strikes on drug targets inside Venezuela, sources say". NBC News. Retrieved 28 September 2025.

- ^ أ ب Cohen, Zachary; Atwood, Kylie; Holmes, Kristen; Treene, Alayna (5 September 2025). "Trump weighs strikes targeting cartels inside Venezuela, part of wider pressure campaign on Maduro, sources say". CNN. Retrieved 6 September 2025.

- ^ أ ب ت Kolster, Nicole (27 September 2025). "The US navy killed 17 in deadly strikes. Now Venezuela is giving civilians guns". BBC News. Retrieved 28 September 2025.

- ^ أ ب Finley, Ben; Toropin, Konstantin; Garcia Cano, Regina (25 September 2025). "Boat strikes, warships and Venezuela rhetoric raise questions about Trump's goals". ABC News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 28 September 2025. Retrieved 28 September 2025.

- ^ أ ب "Why is the U.S. deploying war ships to South America? 4 things to know". PBS. 29 August 2025. Archived from the original on 1 September 2025. Retrieved 1 September 2025.

- ^ "National Drug Control Strategy: Progress in the War on Drugs 1989-1992" (PDF). U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. 1993.

- ^ "Cheney Outlines Role of Military in Drug War: No Arrests, No Raids". Los Angeles Times. 18 September 1989.

- ^ Wilson, George (19 September 1989). "Cheney pledges wider War on Drugs". The Washington Post.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Cooper, Helene; Haberman, Maggie; Savage, Charlie; Schmitt, Eric (8 August 2025). "Trump Directs Military to Target Foreign Drug Cartels". The New York Times. ProQuest 3237712139. Archived from the original on 3 September 2025. Retrieved 2 September 2025.

- ^ Heinz, Brett (23 September 2025). "Proposed war authorization could allow Trump to target 60+ countries". Responsible Statecraft. Retrieved 18 October 2025.

- ^ "Designating Cartels and Other Organizations as Foreign Terrorist Organizations and Specially Designated Global Terrorists". Federal Register. 29 January 2025. Retrieved 5 September 2025.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Pesoli, Mike; Madhani, Aamer; Rueda, Jorge (20 August 2025). "US destroyers head toward waters off Venezuela as Trump aims to pressure drug cartels". Associated Press News. Retrieved 5 September 2025.

- ^ أ ب "US designates group allegedly tied to Venezuela's Maduro for supporting gangs". Reuters. 26 July 2025. Retrieved 5 September 2025.

- ^ أ ب ت Barnes, Julian E.; Pager, Tyler (15 October 2025). "Trump Administration Authorizes Covert C.I.A. Action in Venezuela". New York Times. ProQuest 3261122909. Retrieved 18 October 2025.

- ^ Chutel, Lynsey (9 August 2025). "These Are Drug Cartels Designated as Terrorists by the U.S." The New York Times. ProQuest 3238084073. Archived from the original on 6 September 2025. Retrieved 2 September 2025.

- ^ de Córdoba, José; Fisher, Steve (4 February 2025). "Trump's Next Fight With Mexico: Designating Drug Cartels as Terrorists". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 12 February 2025. Retrieved 2 September 2025.

- ^ أ ب ت Schmitt, Eric (5 September 2025). "What to Know About a Rapid U.S. Military Buildup in the Caribbean". The New York Times. ProQuest 3247135098. Retrieved 11 September 2025.

- ^ "Trump doubles reward to $50 million for arrest of Venezuela's president to face U.S. drug charges". CNN. 8 August 2025. Archived from the original on 2 September 2025. Retrieved 17 September 2025.

- ^ Ali, Idrees; Brendan, O'Boyle (8 August 2025). "Trump administration eyes military action against drug cartels, U.S. officials say". Reuters. Retrieved 5 September 2025.

- ^ أ ب Holland, Steve (18 August 2025). "US deploys warships near Venezuela to combat drug threats, sources say". Reuters. Archived from the original on 21 August 2025. Retrieved 21 August 2025.

- ^ "Trump signs order authorising military action against cartels: Reports". Al Jazeera. 8 August 2025.

- ^ Seligman, Lara; Forrest, Brett (20 August 2025). "Trump Orders Pentagon to Deploy Three Warships Against Latin American Drug Cartels". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 1 September 2025. Retrieved 2 September 2025.

- ^ Ali, Idrees; Zengerle, Patricia; Shalal, Andrea (1 September 2025). "US builds up forces in Caribbean as officials, experts, ask why". Reuters.

- ^ Strobel, Warren P; StanleyBecker, Isaac (17 February 2025). "Under Trump, CIA plots bigger role in drug cartel fight". The Washington Post. ProQuest 3167790585.

- ^ أ ب "Venezuela's Maduro rallies civilian militia volunteers, citing US invasion 'threat'". France 24. 24 August 2025. Archived from the original on 24 August 2025. Retrieved 24 August 2025.

- ^ أ ب Buitrago, Deisy (1 September 2025). "Venezuela's Maduro says U.S. seeking regime change with naval build-up". Reuters.

- ^ "Maduro vows to declare a 'republic in arms' if U.S. forces in the Caribbean attack Venezuela". NBC News. Associated Press. 2 September 2025.

- ^ "USNI News Fleet and Marine Tracker: Sept. 8, 2025". USNI News. 8 September 2025. Archived from the original on 9 September 2025. Retrieved 9 September 2025.

- ^ أ ب Schogol, Jeff; Nieberg, Patty (25 September 2025). "The elusive ship built to carry US special operators is in the Caribbean". Task & Purpose (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 27 September 2025.

- ^ Daftari, Amir (22 September 2025). "US Sends New Missile Destroyer to Caribbean: Map, Photos and What We Know". Newsweek. Retrieved 24 September 2025.

- ^ أ ب Shelbourne, Mallory (14 August 2025). "Iwo Jima Amphibious Ready Group Leaves Norfolk After Long Gap in U.S. ARG Deployments". USNI News. Archived from the original on 7 September 2025. Retrieved 5 September 2025.

- ^ Lowell, Hugo (29 September 2025). "Stephen Miller takes leading role in strikes on alleged Venezuelan drug boats". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 September 2025.

- ^ Schogol, Jeff (19 September 2025). "Why does the US have F-35s flying anti-cartel missions in the Caribbean?". Task and Purpose. Retrieved 29 September 2025.

- ^ Stewart, Phil; Ali, Idrees; Zengerle, Patricia (9 September 2025). "Hegseth says U.S. deployment in Caribbean 'isn't training' on Puerto Rico visit". Reuters. Retrieved 9 September 2025.

- ^ Laporta, James; D'Agata, Charlie (4 September 2025). "Venezuelan fighter jets flew over U.S. Navy ship in "show of force"". CBS News. Retrieved 4 September 2025.

- ^ Inman, Willie James; Jacobs, Jennifer (5 September 2025). "U.S. sending 10 fighter jets to Puerto Rico for operations targeting drug cartels". CBS News. Retrieved 5 September 2025.

- ^ Slayton, Nicholas (12 September 2025). "US deploys MQ-9 Reaper drones to the Caribbean". Task & Purpose (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 14 September 2025.

- ^ Altman, Howard (1 September 2025). "F-35s Arrive In Puerto Rico For Counter-Drug Operation". The War Zone (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 30 September 2025.

- ^ Wells, Ione (5 September 2025). "Rubio says U.S. will 'blow up' foreign crime groups if needed". BBC. Archived from the original on 7 September 2025. Retrieved 8 September 2025.

- ^ "Terrorist Designations of Los Choneros and Los Lobos". U.S. Department of State. 4 September 2025. Retrieved 7 September 2025.

- ^ Janetsky, Megan (23 September 2025). "Trump administration designates Barrio 18 gang as foreign terrorist organization". The Associated Press. Retrieved 16 October 2025.

- ^ "Venezuela says U.S. warship raided a tuna boat as tensions rise in the Caribbean". PBS. 14 September 2025. Retrieved 15 September 2025.

- ^ "With eye on U.S. threat, Venezuela holds Caribbean military exercises". CTV. Retrieved 17 September 2025.

- ^ أ ب Bergengruen, Vera; Gordon, Michael; de Córdoba, José (4 September 2025). "Did a Boat Strike in Caribbean Exceed Trump's Authority to Use Military Force?". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 5 September 2025. Retrieved 5 September 2025.

- ^ Cooper, Helene; Schmitt, Eric; Wong, Edward; Feuer, Alan (2 September 2025). "Trump Says U.S. Attacked Boat Carrying Venezuelan Gang Members, Killing 11". The New York Times. ProQuest 3245739975. Archived from the original on 2 September 2025. Retrieved 2 September 2025.

- ^ Ali, Idrees; Stewart, Phil; Mason, Jeff; Psaledakis, Daphne (3 September 2025). "Trump administration says more operations against cartels coming". Reuters.

- ^ Schmitt, Eric (3 September 2025). "Trump Administration Says Boat Strike Is Start of Campaign Against Venezuelan Cartels". The New York Times. ProQuest 3246084285. Retrieved 4 September 2025.

- ^ Lowell, Hugo; Phillips, Tom (16 September 2025). "Trump announces deadly US strike on another alleged Venezuelan drug boat". The Guardian (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 16 September 2025.

- ^ Buschschlüter, Vanessa; Rawnsley, Jessica (15 September 2025). "US destroys alleged Venezuelan drug boat, killing three". BBC News. Retrieved 15 September 2025.

- ^ Lowell, Hugo (29 September 2025). "Stephen Miller takes leading role in strikes on alleged Venezuelan drug boats". The Guardian (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 29 September 2025.

- ^ Pellish, Aaron (19 September 2025). "Trump details third US strike on suspected drug traffickers". Politico. Retrieved 23 September 2025.

- ^ Madhani, Aamer (19 September 2023). "US has carried out another fatal strike targeting alleged drug-smuggling boat, Trump says". Associated Press News. Retrieved 4 October 2025.

- ^ Savage, Charlie; Jimison, Robert (19 September 2025). "Trump Says U.S. Military Attacked a Third Suspected Drug Boat, Killing Three". The New York Times. ProQuest 3252311049. Retrieved 4 October 2025.

- ^ Rubio, Manuel (22 September 2025). "Dominican Republic says it seized cocaine that was on speedboat destroyed by U.S. Navy". The Associated Press. Retrieved 22 September 2025.

- ^ Flaherty, Anne (3 October 2025). "Hegseth announces another US attack on alleged drug boat off Venezuelan coast". ABC News. Retrieved 3 October 2025.

- ^ Lubold, Gordon; Kube, Courtney (3 October 2025). "U.S. conducts fourth strike on boat it claims was trafficking drugs near Venezuela". NBC News. Retrieved 3 October 2025.

- ^ Delgado, Antonio María; Goodin, Emily (3 October 2025). "U.S. forces in Caribbean sink a fifth suspected drug vessel off Venezuelan coast". Miami Herald. Retrieved 3 October 2025.

- ^ Turkewitz, Julie (8 October 2025). "Colombia's President Says Boat Bombed by U.S. Was Carrying Colombians". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 October 2025.

- ^ Timotija, Filip (14 October 2025). "Trump says 6 killed in strike on 'narcoterrorists' off Venezuela's coast". The Hill. Retrieved 15 October 2025.

- ^ Stewart, Phil; Ali, Idrees (17 October 2025). "Exclusive: U.S. Navy warship holding survivors from strike on Caribbean vessel, sources say". Reuters. Retrieved 17 October 2025.

- ^ Stewart, Phil (17 October 2025). "Exclusive: In a first, US strike in Caribbean leaves survivors, US official says". Retrieved 17 October 2025.

- ^ Megerian, Christ; Coto, Danica; Suarez, Astrid (19 October 2025). "Trump calls Colombia's Petro an 'illegal drug leader' and announces an end to US aid to the country". Associated Press. Retrieved 19 October 2025.

- ^ Schmitt, Eric; Savage, Charlie; Rosenberg, Carol (18 October 2025). "U.S. Is Repatriating Survivors of Its Strike on Suspected Drug Vessel". The New York Times. ProQuest 3262711915. Retrieved 19 October 2025.

- ^ Stewart, Phil; Ali, Idrees (18 October 2025). "Exclusive: US returning Caribbean strike survivors to Colombia and Ecuador, Trump says". Reuters. Retrieved 18 October 2025. Also available at "US military to move survivors of strike on alleged drug boat in Caribbean to nearby countries". The Guardian. Reuters. 18 October 2025. Archived from the original on 18 October 2025. Retrieved 18 October 2025.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Gibbs, Stephen (19 October 2025). "Trump calls Colombian president a 'drug leader' and suspends US aid". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 19 October 2025.

- ^ أ ب ت Faguy, Ana; Armstrong, Kathryn (19 October 2025). "Trump ends aid to Colombia and calls country's leader a 'drug leader'". BBC News. Retrieved 19 October 2025.

- ^ "Colombia ELN rebels deny any involvement with alleged drug boat destroyed by US". Reuters. 21 October 2025. Archived from the original on 22 October 2025. Retrieved 22 October 2025.

- ^ "Pentagon chief announces another US military strike on alleged drug boat in Caribbean". The Guardian. 24 October 2025. Retrieved 24 October 2025.

- ^ María Delgado, Antonio (30 September 2025). "Trump threatens expanded action against Maduro as tensions in the Caribbean escalate". Miami Herald. Retrieved 1 October 2025.

- ^ Madhani, Aamer; Mascaro, Lisa (2 October 2025). "Trump declares drug cartels operating in Caribbean unlawful combatants". ABC News. Associated Press. Retrieved 2 October 2025.

- ^ Savage, Charlie; Schmitt, Eric P. (2 October 2025). "Trump 'Determined' U.S. Is Now in a War With Drug Cartels, Congress Is Told". New York Times. ProQuest 3256385545. Retrieved 2 October 2025.

- ^ Olivares, José; Betts, Anna (2 October 2025). "Trump says drug cartels operating in the Caribbean are 'unlawful combatants'". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 October 2025.

- ^ "El memorando íntegro de la Casa Blanca que declara la guerra a los carteles de droga" [The full White House memo declaring war on drug cartels]. La Patilla (in الإسبانية). 3 October 2025. Retrieved 3 October 2025. English version follows Spanish translation.

- ^ McCarthy, Andrew C. (3 October 2025). "Trump's War Notice: The 'Nonstate Actor' Issue". National Review. Retrieved 4 October 2025.

- ^ McCarthy, Andrew C. (2 October 2025). "Trump Notifies Congress That the U.S. Is at War with Drug Cartels". National Review. Retrieved 3 October 2025.

- ^ Goodin, Emily; Delgado, Antonio Maria (2 October 2025). "Trump declares U.S. in 'armed conflict' with drug cartels". Miami Herald. Retrieved 2 October 2025.

- ^ Robertson, Noah; Horton, Alex; Nakashima, Ellen; DeYoung, Karen (2 October 2025). "U.S. in 'armed conflict' with drug cartels, Trump tells Congress". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2 October 2025.

- ^ Rios, Michael (2 October 2025). "Venezuela says it detected 5 US 'combat planes' flying 75km from its coast, calls it a 'provocation'". CNN. Retrieved 4 October 2025.

- ^ أ ب Wong, Edward; Schmitt, Eric; Turkewitz, Julie (8 October 2025). "Qatar Pushes U.S.-Venezuela Diplomacy as Trump Focuses on Military Action". The New York Times. ProQuest 3258631586. Retrieved 10 October 2025.

- ^ Ruiz, Roque; Holliday, Shelby; Churchill, Carl (14 October 2025). "See Advanced Weaponry the U.S. Is Deploying to the Caribbean; U.S. military buildup includes F-35B jets, reaper drones and 10,000 troops—too few to invade Venezuela but enough to support more airstrikes". Wall Street Journal. ProQuest 3260774973. Retrieved 18 October 2025.

- ^ أ ب Forero, Juan; Vyas, Kejal; de Córdoba, José; Seligman, Lara (17 October 2025). "Venezuela Mobilizes Troops and Militias as U.S. Military Looms Offshore; Maduro says his country is ready for combat, though its military is underfunded, ill-trained and no match for American firepower". Wall Street Journal. ProQuest 3261880496. Retrieved 17 October 2025.

- ^ Shalal, Andrea (6 October 2025). "Trump calls off diplomatic outreach to Venezuela, US official says". Reuters. Retrieved 10 October 2025.

- ^ أ ب Delgado, Antonio María (16 October 2025). "Exclusive: Venezuelan leaders offered U.S. a path to stay in power without Maduro". Miami Herald. Retrieved 18 October 2025.

- ^ أ ب Delgado, Antonio María (17 October 2025). "Venezuelan leaders deny Miami Herald report they offered U.S. to have Maduro step down". Miami Herald. Retrieved 17 October 2025.

- ^ أ ب Madhani, Aamer; Klepper, David (16 October 2025). "Venezuela floated a plan for Maduro to slowly give up power, but was rejected by US, AP source says". Associated Press. Retrieved 17 October 2025.

- ^ "Colombia's Petro urges 'criminal trial' against Trump for Venezuelan strikes". The Guardian. Agence France Presse. 24 September 2025.

- ^ Mendoza, Diego; Symons, Todd (27 September 2025). "US revokes visa of Colombia's Petro after he called on soldiers to disobey Trump". CNN. Retrieved 25 October 2025.

- ^ Umaña Mejía, Fernando (18 October 2025). "Gustavo Petro dice que lanchero abatido en operación antidrogas por Estados Unidos el 16 de septiembre era un pescador colombiano" [Gustavo Petro says the boatman killed in a U.S. anti-drug operation on 16 September was a Colombian fisherman]. El Tiempo (in الإسبانية). Retrieved 19 October 2025.

- ^ Phillips, Tom; Barber, Harriet; Duncan, Natricia (9 October 2025). "President Petro accuses US of killing Colombians in attacks on 'narco-boats'". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 October 2025.

- ^ Psaledakis, Daphne; Symmes Cobb, Julia; O'Boyle, Brendan (24 October 2025). "US sanctions Colombia's president, accuses him of allowing expansion of drug trade". Reuters. Retrieved 25 October 2025.

- ^ Stewart, Phil (11 October 2025). "US military hikes operational command of counter-narcotics operations in Latin America". Reuters. Retrieved 17 October 2025.

- ^ Timotija, Filip (10 October 2025). "Hegseth announces task force to 'crush' drug cartels in Caribbean Sea". The Hill. Retrieved 17 October 2025.

- ^ Schmitt, Eric; Pager, Tyler (16 October 2025). "Head of the U.S. Military's Southern Command Is Stepping Down, Officials Say". New York Times. ProQuest 3261806755. Retrieved 18 October 2025.

- ^ Lawrence, Drew F. (22 October 2025). "Air Force B-52 bombers flew 'attack demonstration' near Venezuela". Task & Purpose. Retrieved 22 October 2025.

- ^ أ ب ت Trevithick, Joseph (2025-10-23). "B-1 Bombers Fly Off Venezuela's Coast". The War Zone (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2025-10-25.

- ^ Seligman, Shelby Holliday and Lara (2025-10-23). "Exclusive | U.S. Sends B-1 Bombers Near Venezuela, Ramping Up Military Pressure". The Wall Street Journal (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2025-10-25.

- ^ Schmitt, Eric; Savage, Charlie; Cameron, Chris (22 October 2025). "U.S. Strikes 2nd Boat in Pacific as Anti-Drug Operation Expands". New York Times. ProQuest 3263873838. Retrieved 22 October 2025.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Lamothe, Dan (24 October 2025). "Pentagon orders aircraft carrier to Latin America as Trump signals escalation". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 24 October 2025. Retrieved 24 October 2025.

- ^ Treene, Alayna; Atwood, Kylie; Lillis, Katie Bo (24 October 2025). "Trump considering plans to target cocaine facilities inside Venezuela, officials say". CNN. Retrieved 24 October 2025.

- ^ Holliday, Shelby; Seligman, Lara (24 October 2025). "Pentagon Orders Aircraft Carrier to the Caribbean; Move is strongest sign yet that Trump administration envisions expanding its military campaign in region". Wall Street Journal. ProQuest 3264633521. Retrieved 24 October 2025.

- ^ Savage, Charlie; Schmitt, Eric (24 October 2024). "U.S. Deploys Aircraft Carrier to Latin America as Drug Operation Expands". New York Times. ProQuest 3264578050. Retrieved 25 October 2025.

- ^ أ ب Trevithick, Joseph (2025-10-24). "Supercarrier USS Ford Being Pulled From Europe And Ordered To Caribbean". The War Zone (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2025-10-25.

- ^ Madhani, Aamer; Toropin, Konstantin; Garcia Cano, Regina (3 September 2025). "Trump says US strike on vessel in Caribbean targeted Venezuela's Tren de Aragua gang, killed 11". Associated Press News. Retrieved 3 September 2025.

- ^ Daniels, Joe (1 October 2025). "US naval build-up bolsters Venezuelan opposition, leader-in-hiding says". Financial Times. Retrieved 1 October 2025.

- ^ "Venezuela's Maduro orders new military exercises after U.S. military blows up another alleged drug boat in Caribbean - CBS News". www.cbsnews.com (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 15 October 2025. Retrieved 16 October 2025.

- ^ "At UN, Colombia's Petro urges 'criminal process' against Trump for Caribbean strikes". CTV. Retrieved 23 September 2025.

- ^ أ ب "La Celac expresa 'profunda preocupación' ante el despliegue naval de Estados Unidos" [CELAC expresses 'deep concern' over the US naval deployment]. CNN en Español (in الإسبانية). 5 September 2025. Retrieved 9 September 2025.

- ^ "Despliegue militar de EE. UU. en el Caribe: Colombia alerta por 'invasión extranjera' tras reunión extraordinaria de la Celac" [US military deployment in the Caribbean: Colombia warns of 'foreign invasion' after extraordinary CELAC meeting]. El Colombiano (in الإسبانية). 8 September 2025. Retrieved 9 September 2025.

- ^ "Mayoría de la Celac rechaza despliegue 'extrarregional' del Pentágono" [Majority of CELAC rejects the Pentagon's 'extraregional' deployment]. La Jornada (in الإسبانية). 6 September 2025. Retrieved 9 September 2025.

- ^ أ ب "Amid face-off between U.S. and Venezuela, fishermen in Trinidad and Tobago fear for their lives and jobs". CBS News. 6 October 2025. Retrieved 8 October 2025.

- ^ "Trinidad to give U.S access to defend Guyana if necessary". St. Vincent Times. 24 August 2025. Retrieved 8 October 2025.

- ^ Davis, Jovani (15 September 2025). "Venezuela's Maduro accuses Trinidad and Tobago Prime Minister of threatening war". Caribbean National Weekly. Retrieved 8 October 2025.

- ^ "Trinidad and Tobago leader praises strike and says US should kill all drug traffickers 'violently'". Associated Press News. 3 September 2025. Retrieved 3 September 2025.

- ^ Muñoz, Marleidy (29 August 2025). "Reactions to US Deployment of Warships in the Caribbean". Havana Times. Archived from the original on 7 September 2025. Retrieved 5 September 2025.

- ^ Ewing-Chow, Daphne (15 September 2025). "Cayman on alert as US escalates Caribbean drug operations". Cayman Compass. Retrieved 2 October 2025.

- ^ "Tractatenblad van het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden". Netherland.nl. 2 March 2000. Retrieved 30 September 2025.

- ^ أ ب "Curaçao Government Favors Extension of U.S. FOL Agreement Until 2026". Curacao Chronicle. 19 September 2025. Retrieved 30 September 2025.

These consultations led to the deployment of an additional Dutch naval vessel in the Caribbean.

- ^ "U.S.–Venezuela Tensions Spark Anxiety in Curaçao". Curacao Chronicle. 29 August 2025. Retrieved 1 October 2025.

- ^ "Curacao staying neutral amid rising tensions between U.S., Venezuela". NL Times (Netherlands Times). 26 August 2025. Retrieved 1 October 2025.

- ^ "Kingdom Distances Itself from U.S. Military Buildup Near Venezuela". The Curacao Chronicle. 29 August 2025. Retrieved 29 September 2025.

- ^ Charles, Jacqueline; María Delgado, Antonio (9 October 2025). "Grenada weighs U.S. radar proposal linked to anti-drug campaign targeting Venezuela". The Miami Herald. Retrieved 15 October 2025.

- ^ Wilkinson, Bert (13 October 2025). "Calls for Grenadians to reject US request to set up radar station". Caribbean Life. Retrieved 15 October 2025.

- ^ "Grenada opposition MP says US should not be allowed to set up military base". Trinidad and Tobago Guardian. 14 October 2024. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- ^ Clark, Joanne (15 October 2025). "Antigua and Barbuda rejects hosting US military assets". Caribbean News Weekly. Retrieved 16 October 2025.

- ^ "PM Browne Rules Out Hosting Foreign Military Assets in Antigua and Barbud". Antigua.news. 15 October 2025. Retrieved 16 October 2025.

- ^ Davis, Jovani (17 October 2025). "CARICOM leaders discuss US radar request in Grenada". Caribbean National Weekley. Retrieved 20 October 2025.

- ^ أ ب ت Delgado, Antonio María (2 October 2025). "Caribbean route shut down: How U.S. forces hit Venezuela's drug network". Miami Herald. Retrieved 2 October 2025.

- ^ أ ب Julian E. Barnes; Edward Wong; Julie Turkewitz; Charlie Savage (29 September 2025). "Top Trump Aides Push for Ousting Maduro From Power in Venezuela". The New York Times. ProQuest 3255480638.

- ^ Turkewitz, Julie; Loureiro Fernandez, Adriana (28 September 2025). "Fear and Hope in Venezuela as U.S. Warships Lurk". The New York Times (in الإنجليزية). ProQuest 3255092122. Retrieved 10 October 2025.

- ^ Phillips, Tom (2 September 2025). "US conducts 'kinetic strike' against drug boat from Venezuela, killing 11, Trump says". The Guardian (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2 September 2025.

- ^ أ ب Murphy, Matt; Cheetham, Joshua (4 September 2025). "US strike on 'Venezuela drug boat': What do we know, and was it legal?". BBC. Archived from the original on 3 September 2025. Retrieved 5 September 2025.

- ^ "right of hot pursuit". Oxford Reference. Archived from the original on 7 September 2025. Retrieved 5 September 2025.

The right of a coastal state to pursue a foreign ship within its territorial waters ... and there capture it if the state has good reason to believe that this vessel has violated its laws. The hot pursuit may – but only if it is uninterrupted – continue onto the high seas ...

- ^ Savage, Charlie (4 September 2025). "Trump Claims the Power to Summarily Kill Suspected Drug Smugglers". The New York Times. ProQuest 3246821029. Archived from the original on 4 September 2025. Retrieved 4 September 2025.

- ^ Rona, Gabor (2 October 2025). "Venezuelan Boat Attacks: Utterly Unprecedented and Patently Predictable". Lawfare. Retrieved 2 October 2025.

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- CS1 الإنجليزية البريطانية-language sources (en-gb)

- CS1 الإسبانية-language sources (es)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- مقالات ذات عبارات بحاجة لمصادر

- فترة ما بعد الحرب الباردة

- الحرب على المخدرات

- نزاعات القرن 21

- نزاعات عقد 2020

- مكافحة الإرهاب في الولايات المتحدة

- عمليات مكافحة الإرهاب

- نزاعات 2025

- أغسطس 2025 في الولايات المتحدة

- أغسطس 2025 في أمريكا الجنوبية

- عمليات عسكرية في 2025

- 2025 في الكاريبي

- 2025 في العلاقات الدولية

- 2025 في ڤنزويلا

- التاريخ العسكري للولايات المتحدة في القرن 21

- الأزمة في ڤنزويلا

- تاريخ إدارة المخدرات

- سبتمبر 2025 في أمريكا الجنوبية

- جدل الرئاسة الثانية لدونالد ترمپ

- البحرية الأمريكية في القرن 21

- العلاقات الأمريكية الڤنزويلية

- عمليات عسكرية ضد الجريمة المنظمة

- جدل گوستاڤو پترو

- جدل نيكولاس مادورو