شارل الجسور

| شارل الجسور | |

|---|---|

شارل الجسور شاباً، رسم روگير ڤان در ڤيدن. | |

| دوق برگندي | |

| العهد | 15 يونيو 1467 – 5 يناير 1477 |

| سبقه | فليپ الطيب |

| تبعه | ماري |

| وُلِد | 10 نوفمبر 1433 ديجون، برگندي |

| توفي | 5 مايو 1477 نانسي، لورين |

| Spouse | |

| الأنجال | ماري دوقة برگندي |

| البيت | آل ڤالوا |

| الأب | فيليپ الطيب |

| الأم | إيزابلا من الپرتغال |

| الديانة | Roman Catholicism |

| التوقيع | |

شارل الجسور Charles the Bold (أو شارل المتهور) (فرنسية: Charles le Téméraire or Charles le Hardi، هولندية: Karel de Stoute)[1] (10 نوفمبر 1433 – 5 يناير 1477)، طُوب باسم شارل مارتين، كان دوق برگندي من1467 حتى 1477. اشتهر لدى أعداؤه باسم شارل الرهيب،[2] كان آخر دوقات برگندي من آل ڤالوا وكانت لوفاته المبكرة، أثراً محورياً في التاريخ الأوروپي.

بعد وفاته، انقسمت مملكته بين فرنسا والهابسبورگين (الذين بحكم زواجهم من وريثة عرشه ماري أصبحوا ورثة للعرش). لم يرضى أي من الجانبين عن هذه النتائج وعن تقسيم الدولة البرگندية، الذي أدى كان سبباً رئيسياً في قيام أقوى الحروب في أوروپا الغربية لأكثر من عقدين.

حياته

تبخر هذا الفوران كله بفضل حدة مزاج شارل المتهور، الملقب خطأ بالجسور. وهو الذي صوره روجيه فان درويدن، في صورة كونت شاروليه الفتى الجميل الحاد ذي الشعر الأسود، الذي قاد جيوش أبيه، في انتصارات دامية، وعرك سلطان أبيه منتظراً وفاته. ففي عام 1465 أحس فليپ الطيب بنفاذ صبره، فسلم إليه مقاليد الحكم، وأشبع بذلك طموح الشاب ونشاطه. [3]

.

وأبى شارل تقسيم دوقيته إلى ولايات شمالية وأخرى جنوبية تتفرق مكاناً وتتعدد لغة، وأبى فوق ذلك الولاء الإقطاعي الذي يدين به عن بعض هذه الولايات لملك فرنسا، وعن بعضها الآخر لإمبراطور ألمانيا. وكان مشوقاً لتحقيق برجنديا العظمى، مثل لوثارينجيا (لورين) في القرن التاسع، لتكون مملكة وسطى بين ألمانيا وفرنسا، موحدة من الناحية الطبيعية، ذات سيادة من الناحية السياسية. ولقد فكر أحياناً، في أن وفيات بعض أولياء العهود الذين يتداخلون في نسبه في الوقت المناسب، قد تسلمه العروش الفرنسية والإنجليزية والإمبراطورية، وتسمو به إلى مصارف أرفع الشخصيات في التاريخ مكانة. ولقد نظم، تحقيقاً لهذه الأحلام، أحسن جيش عامل في أوربا، وفرض على رعاياه من الضرائب ما لا نظير له في الماضي، وكيف نفسه لمكابدة كل عناء وتجربة، ولم يمنح عقله وجسمه، ولا أصدقاءه وأعداءه، فترة من الراحة والسلام.

معاهدة پيرون

ومع ذلك: فقد فكر لويس الحادي عشر، في برجنديا باعتبارها إقطاعية من ملك فرنسا، وحارب تابعه الغني متفوقاً في الخطط والدسائس-فانضم شارل إلى النبلاء الفرنسيين ضد لويس، وغنم مدناً أخرى، والعداوة الدائمة لملك عنيد. وفي هذا الصراع انتقضت دينان ولييج على برجنديا، وأعلنا ولاءهما لفرنسا، كتب بعض المتحمسين في دينان Dinant، على صورة معلقة لشارل، إنه ابن سفاح لقسيس لمستهتر. فهدم شارل أسوار المدينة بالمدافع، وأباحا لجنوده ثلاثة أيام ينهبونها، واسترق جميع رجالها، وشرد كل نسائها وأطفالها، وأحرق جميع مبانيها حتى أصبحت أثراً بعد عين، وألقى بثمانمائة من الثائرين مقيدة أيديهم وأرجلهم من خلاف في نهر الموز (1466) ومات فيليب في شهر يونيو التالي، وأصبح كونت شاروليه، شارل الجسور. فأعاد الحرب مع لويس، وأجبر لييج التي ثارت مراراً بمحاصرتها، على أن تؤيده وتعاونه في هذه الحرب. وقدم سكان المدينة المتضرعون جوعاً، جميع ما يمتلكون ثمناً لحياتهم.. فرفض العرض، وأباح المدينة، ولم ينج من النهب بيت أو كنيسة، وانتزعت كؤوس القربان من أيدي القساوسة وهم يقومون بالصلاة، وأغرق جميع الأسرى الذين عجزوا عن دفع الدية الباهظة (1468).

والعالم، وإن تردى، طويلاً في أعمال العنف، لا يستطيع أن يغتفر لشارل قسوته، وخروجه على تقاليد الإقطاع في حبس مليكه وإذلاله. فلما غزا جلدرلاند، وحصل على الألزاس، وتقدم بخطى إمبراطور ليتدخل في كولونيا ومحاصرة نيس Neuss. بادر جميع جيرانه إلى الوقوف بوجهه. وأسخط بيتر فان هاجنباك، الذي عينه والياً على الألزاس، الناس لفظاظته وجوره وقسوته، فشنقوه، وأعلن الاتحاد السويسري محاربة شارل إلى الموت (1474) ذلك لأن التجار السويسريين كانوا من ضحايا بيتر، والذهب الفرنسي كان يوزع من الناحية العسكرية في سويسرا، والولايات السويسرية، كانت تحس بأن اتساع سلطان شارل خطر يهدد حريتها. فترك نيس، واتجه ناحية الجنوب، فغزا اللورين-موحداً لأول مرة طرفي دوقيته-وسير جيشه عبر جورا، إلى فود. وكان السويسريون أشجع الجنود في عصرهم، فهزموا شارل بالقرب من جرانسن، ثم دحروه بالقرب من مورات (1476) وهكذا اكتُسح البرجنديون،

السياسات

التشريع

Upon his ascension as duke in 1468, Charles sought to dismantle the jurisdiction of the Parlement of Paris as the highest juridical power within his country. The cities and institutions in Burgundy relied on the parlement for challenging legal decisions. This irritated the Dukes of Burgundy who detested any reliance on France. Philip the Good had established an itinerant, but less powerful, court of justice that travelled all across the country.[4] Charles established a central sovereign court in Mechelen under his 1473 ordinance of Thionville. The city would house the new Court of Auditors, which previously resided in Lille and Brussels. The language of this parliament was French, with two-thirds of its personnel being Burgundian.[5] The Mechelen parliament only held authority in the Low Countries. In the Burgundian mainlands, Charles established another parliament whose seat moved between Beaune and Dole.[6]

In Charles's own words, the proper administration of justice was "the soul and the spirit of the public entity."[7] He was recognised as the first sovereign to make a serious effort to impose peace and justice upon the Low Countries, and he was regarded as "a prince of Justice" by historian Andreas van Haul, a century after his death.[8] However, Georges Chastellain criticized Charles for his lack of mercy while imposing justice.[9] Charles damaged his relations with his people by inspecting and regulating every aspect of their lives, and he was unnecessarily harsh.[10] Charles wanted to reduce the influence of the local aldermen, who were viewed by the commoners as the local court, and he undermined the Mechelen parliament.[8] To both increase his grip on the seats of justice and to fill up his treasury, Charles dismissed the aldermen and sold their offices to the highest bidders; only the wealthiest subjects came to hold those positions.[8] Many institutions protested against these practices, but Charles persisted because he constantly needed to fund his armies.[11]

الدين

Charles the Bold was religious, and regarded himself as more devout and pious than any ruler of his day.[12] He considered his sovereignty as bestowed upon him by God and thus owed his power to God alone.[13] From a young age, Charles chose Saint George as his patron saint.[14] He kept a sword purported to have belonged to Saint George in his treasury, and he revered other warrior saints, such as Saint Michael.[15] He commissioned a prayer book, from Lieven van Lathem, which was completed in 1469.[16] The opening diptych of the manuscript, as well as two other pieces, demonstrate Charles's devotion to Saint George.[14] In Margaret of York's copy of La Vie de Sainte Colette, she and Charles are shown as devotees of Saint Anne. Multiple modern scholars, such as Jeffrey Chipps Smith, have made a connection between the saint and the duke from the fact that both were married three times. According to Nancy Bradley Warren, the portrayal of Charles and Saint Anne may have been a way to legitimise his marriage to Margaret and reassure those who were dubious regarding an alliance with England.[17]

Throughout his reign, Charles faced multiple requests to pledge his men to a crusade against the Ottoman Empire.[18] Pope Sixtus IV sent three instructions to the papal legate at the Burgundian court, Lucas de Tollentis, directing him to encourage Charles to undertake a crusade against the Ottomans.[19] Tollentis reported to the Pope on 23 June 1472 that Charles was "resolved in our favour", and the welfare of Christendom was never far from his mind.[20] Charles may have considered an expedition to the east as the climax of his life's work; however, during his lifetime, he never undertook a crusade nor did he make preparations for it as his father had.[21] Only for a short time, between late 1475 and early 1476, did he seriously consider a crusade and that was only after a meeting with Andreas Palaiologos, the deposed Despot of the Morea, who agreed to cede his claim as the Emperor of Trebizond and Constantinople to Charles.[22][23][أ]

الدبلوماسية

Charles the Bold pursued a risky and aggressive foreign policy.[24] Trying to have as many allies as possible, he considered everyone, aside from Louis XI, as his ally.[25] In 1471, he made a list of his nineteen allies. He increased the number to twenty-four by the next year and had twenty-six allies in 1473, in contrast to Louis XI's fifteen allies.[25] Some of these relations, such as with Scotland, were only formalities. The kings of Scotland and Denmark would also sign treaties with Louis XI and appear on his list of allies.[26]

Initially, Charles was hesitant about an alliance with Matthias Corvinus, the king of Hungary.[27] However, the mutual friendship with the Kingdom of Naples brought Burgundy and Hungary closer to each other, and in his pursuit to ally with Frederick III's opponents, Charles made contact with Matthias.[28] Charles hoped that by supporting Matthias' claim to the Kingdom of Bohemia, Matthias would back him in the electoral college.[29] In November 1474, the two successfully concluded a treaty by which they agreed to partition the Holy Roman Empire between themselves, with Charles becoming the king of the Romans and having the lands along the Rhine under his authority while Matthias would acquire Breslau and Bohemia.[30] In 1473, through negotiations with the new Duke of Lorraine, René II, Charles obtained the right to pass his armies through the duke's lands, and assign Burgundian captains to important fortifications in Lorraine, essentially turning the duchy into a Burgundian protectorate.[31] Among Charles's other allies were Amadeus IX, Duke of Savoy, whose wife, Yolande of Valois, Louis XI's sister, drove the duchy into an alliance with Burgundy on the basis of their shared dislike of Louis XI.[32]

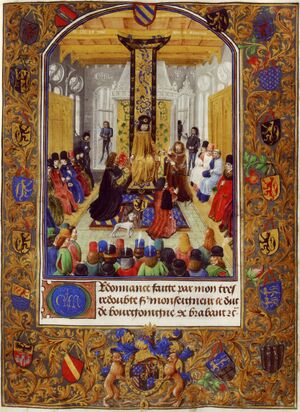

The intense rivalry between Louis XI and Charles kept both rulers always prepared for an eventual war.[33] The suspicious death of Charles of Valois, Duke of Berry, the king's brother, in 1472, prompted Charles to raise arms to avenge his ally's death, stating that Berry had been poisoned by Louis.[34] After a short conflict, the two ceased their fighting in the winter 1473 without any talk of peace. Neither would declare war on the other for the rest of their reigns.[35] In 1468, Charles and Louis tried to make peace, which astonished the rest of France.[36] Their peace talks soon turned into hostility once Charles learned that Louis had his hands in a recent rebellion in Liége.[37] Afterwards, Charles imprisoned Louis in the city of Péronne and coerced him into signing a treaty favourable to Burgundy, with conditions such as forfeiting the Duke of Burgundy from paying homage, guarantying Charles's sovereignty over Picardy, and abolishing French jurisdiction over Burgundian subjects.[38] Louis reluctantly agreed to all the demands and signed the Treaty of Péronne.[39] However, the crown did not abide by the treaty terms and Franco-Burgundian relations remained poor.[40]

في إيطاليا

At the start of Louis XI's reign, Italy's triple alliance between the Duchy of Milan, the Republic of Florence, and the Kingdom of Naples, allowed the influence of France grow in the peninsula, for Milan and Florence were long-standing allies of Louis.[41] To remedy this, Charles enlarged Burgundy's sphere of influence in Italy to dwarf that of France.[42] The first Burgundian alliance with an Italian ruler was with King Ferdinand I of Naples, a ruler admired by both Charles and Louis.[43]

Ferdinand was the legitimised bastard of Alfonso I, and the Pope did not recognize his claim to the throne.[44] Meanwhile, René of Anjou, the deposed King of Naples, persistently sought his title back. In the constant fear of an invasion from René or his heirs with the support of Louis XI, Ferdinand allied himself with Charles, who made Ferdinand a member of the Order of the Golden Fleece in 1473.[45] Charles constantly toyed with the idea of marrying his daughter, Mary, to Ferdinand's second son, Frederick of Naples, who visited the Burgundian court in 1469 and 1470.[46] In 1474, when war with Louis XI was on the horizon, Ferdinand's participation was dependent on his son's marriage to Mary. Charles hinted at his willingness to give his daughter's hand to Frederick, and Ferdinand dispatched his son to Burgundy on 24 October 1474.[47] Although Frederick became a lieutenant and close military advisor to Charles, he failed in his ultimate mission of marrying Mary.[48]

The Duchy of Milan was France's most important ally in the Italian peninsula; Milan's ruler, Galeazzo Maria Sforza was attached to the King of France through his marriage with Louis' niece, Bona of Savoy.[49] Charles tried to form an alliance with Milan. In 1470, he offered Galeazzo membership in the Order of the Golden Fleece, on the premise of an alliance, but was rejected.[50] One time he even included Milan on one of his lists of allies, which caused Galeazzo to protest.[25] To bring Galeazzo into alliance, Charles started a rumour that he wished to conquer Milan.[51] Concerns about a probable war, and Charles's bringing diplomatic pressure to isolate Milan from France, persuaded Galeazzo to sign a treaty, on 30 January 1475 at Moncalieri, that formed an alliance between Savoy, Burgundy, and Milan.[52] As a result of this treaty, diplomatic relations between the two duchies were established, and Galeazzo sent Giovanni Pietro Panigarola as his envoy to Burgundy.[53]

Charles's relation with the Republic of Venice was based on his willingness to launch a crusade against the Turks.[54] With Ferdinand of Naples's insistence, the senate of Venice agreed to a treaty against the King of France on 20 March 1472.[55] From then on, Venice constantly urged Charles to uphold his part of the bargain and support them in their war with the Ottomans.[56] Charles's inaction led to gradual estrangement from Venice.[57] For instance, when he wanted to recruit the Venetian condottiero Bartolomeo Colleoni (who would have brought with him 10,000 men at arms) to his ranks, the Venetian government did not allow Colleoni to go. Charles spent two years negotiating with the Venetian ambassadors, but in the end, was unsuccessful in convincing them.[58] By 1475, the alliance between Venice and Burgundy had ceased to seem like a genuine union.[59]

The Italian peninsula saw a shift in spheres of influence after the Treaty of Moncalieri in 1475. Charles the Bold triumphantly replaced Louis XI as the dominant influence in Italian politics, with three of four major secular powers in the region—Milan, Naples, and Venice—all aligned with him.[60] Only Florence remained a French ally, though they remained neutral toward Charles on the basis of their mutual alliance with Venice.[61] Charles successfully eliminated any possible Italian support for France, and now could count on the support of his Italian allies if a war with France ensued.[60] However, from 1472, relations with France amounted to a truce, and remained as such during rest of Charles's reign.[62]

الفنون

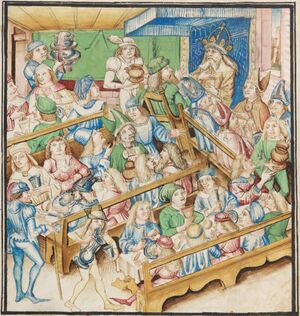

The Burgundian court under Charles the Bold was famous and magnificent.[63] It was seen as a place to learn arts and etiquette and where chivalry and courtly life were more intact than in the rest of the Europe. For this reason, the Burgundian court was the host to many young noblemen and princes from all across the continent.[64] Even future generations admired Charles's court. Philip II, for instance, at the urging of his father, Charles V, introduced the "ceremonial of the court of Burgundy" into Spain, using Olivier de la Marche's account of Charles the Bold's court.[65] Charles's Burgundian court thus became the idealized courtly life that sparked inspiration throughout 17th century Spain.[66] While Charles's court did not differ much from those of his contemporaries, certain special features increased the court's appeal: the number of knights and nobles, the sacred image of the ruler who was distant from other courtiers, and the splendour of the court.[67] Charles, like his predecessors, displayed his glamour through extravagant patronage of the arts.[68]

During Charles's reign, the production of illuminated manuscripts flourished.[69] After his ascension in 1467, Charles provided considerable funds for projects left incomplete after his father's death and commissioned new projects as well.[70] As a patron of Renaissance humanism, he commissioned the translation of Quintus Curtius Rufus's Histories of Alexander the Great into French to replace the inadequate Roman d'Alexandre en prose. He commissioned the Portuguese Vasco de Lucena and Jehan de Chesne to respectively translate Xenophon's Cyropaedia and Caesar's De bello Gallico into French.[71] In 1468, he commissioned Guillaume Fillastre to compose a "didactic chronicle" called Histoire de Toison d'Or containing moral and didactic stories of Jason, Jacob, Gideon, Mesha, Job, and David.[72] He employed the finest calligraphers and illuminators to engross his ordinances; the Ordinance of 1469 was illuminated by Nicolas Spierinc and was distributed among Charles's courtiers.[73] His prayer book illuminated by Lieven van Lathem is considered a masterpiece of Flemish illumination that influenced great illuminators such as the Master of Mary of Burgundy.[74] Charles and his wife Margaret were patrons of Simon Marmion, who illuminated a breviary and a panel painting for them.[75]

Charles was a patron of music and was a capable musician.[76] In his 1469 ordinance, Charles gave a clear view of what his musical entourage should be: a concert band, ceremonial trumpeters, chamber musicians, an organist, and the chapel musicians, whose music had more variety than that of Philip the Good's chapel.[77] He brought his chapel with himself on his campaigns and had choristers sing a new song to him every night in his chambers.[78] Charles was a patron of the composer Antoine Busnois, who became his choirmaster;[79] his court musicians also included Hayne van Ghizeghem and Robert Morton.[80] His favourite song was L'homme armé, a song that may have been written for him.[81] Charles composed a motet that was sung in the Cambrai Cathedral, presumably in the presence of Guillaume Du Fay, one of the most well-known composers of his era.[82] Among his other works were chansons and secular songs.[83] Although no pieces from his motet or chansons remain, two songs are attributed to him: Del ducha di borghogna (of the Duke of Burgundy) and Dux Carlus (Duke Charles). Both are from Italian songbooks wherein no name of the composers is mentioned. Nevertheless, the songs have uncanny similarities to each other: in voice ranges, in their use of pitch C, their musical form (rondeau), and both songs start with the phrase Ma dame. According to the musicologist David Fallows, with such similar traits, the songs are most likely both composed by Charles in the 1460s.[84] Charles also liked to sing; however, he did not have a good singing voice.[85]

العسكرية

When Charles became the Duke of Burgundy, his army functioned under a feudalistic system, with most of its men either recruited through summons or hired under contract. The majority of his army consisted of French nobles, and their retainers, and English archers; this army suffered from an inefficient distribution of resources and slow movement.[86] Having lived through a period of peace under Philip the Good, the army scarcely trained and was unprepared. Furthermore, in comparison to other armies of Europe, their structure was outdated.[87] To remedy these problems, Charles issued a series of military ordinances, between 1468 and 1473, that not only would revolutionise the Burgundian army, but also would influence every European army in the 16th century.[88] The first of these ordinances, addressed to the Marshal of Burgundy, contains instructions on who could be recruited to the army and describes the personnel of the artillery: namely, masons, assistants, cannoneers, and carpenters.[89] The second ordinance, issued at Abbeville in 1471, proclaimed the formation of a standing army, called Compagnie d'ordonnance, made up of 1250 lances fournies, who were accompanied by 1200 crossbows, 1250 handgunners, and 1250 pikemen.[90] A squad consisted of a man-at-arms, a mounted page, a mounted swordsman, three horse archers, a crossbowmen, and a pikeman. Charles designed a uniform for each of the companies (Cross of Burgundy inscribed on the ducal colours).[91] He also designed an overlapping military hierarchy that sought to preclude the infighting between captains and their subordinates that would arise in a pyramidal hierarchy.[92]

The last of these ordinances, issued at Thionville, marked the culmination of Charles's martial administration. The organisation of a squad was categorised to the merest detail; specific battle marches were created to keep order between the men; a soldier's equipment were explained in detail, and discipline among the ranks was regarded as of the utmost importance.[93] Charles forbade individual soldiers to have a camp follower, instead, he permitted each company of 900 to have 30 women in their ranks who would attend to them.[91] He set brutal rules against defaulters and deserters. In 1476, he appointed Jehan de Dadizele to arrest deserters. Those guilty of encouraging soldiers to desert were to be executed and the deserters were to return to the army.[94] Charles intended for his soldiers to tutor their compatriots about these new conditions in private settings without a disciplinarian presiding over them.[92] Charles's erratic pace in promulgating new, detailed reforms every few years was too much for his captains and men-at-arms to sufficiently implement.[95]

Charles's ordinances were mostly inspired by Xenophon's Cyropaedia.[96] After observing how Cyrus the Great achieved the willing obedience of his subjects, Charles became obsessed with discipline and order among his men-at-arms.[97] He applied Xenophon's comments in the Abbeville ordinance, thus ensuring that through a complex chain of command, his soldiers would both command and obey.[92] The influence of Vegetius's De re militari is also quite apparent in Charles's writings. Vegetius suggested that soldiers were to be recruited from men offering themselves to a martial life; afterwards, they would swear an oath to stay loyal to the duke. Charles adapted both ideas in his 1471 ordinance.[98] Charles's 1473 ordinance included exercises from Vegetius to keep soldiers disciplined and prepared.[99]

The Burgundian standing army struggled with recruitment.[100] Although the army had enough men-at-arms, pikemen, and mounted archers, it lacked culverins and foot archers.[101] To solve this problem, Charles diversified his army and recruited from other nationalities.[102] Italian mercenaries were his favourite and by 1476 filled most of his ranks.[103] Despite the constant warning from military authors of the past against the recruitment of mercenaries, contemporary chronicler Jean Molinet praised Charles for his brilliant solution, saying that he was favoured by both heaven and earth and thus above the "commandments of philosophers".[104]

الحروب البورجندية

عصبة كونستانس

Over the span of five years, Charle's deputy in Upper Alsace, Peter von Hagenbach, alienated his Alsatian subjects; antagonized the neighbouring Swiss Confederacy, who felt threatened by his rule; and showed aggressive intentions towards the city of Mulhouse. As a result, the Swiss sought alliances with German towns and Louis XI.[101] By February 1473, a handful of free cities had combined to end Burgundian rule in Alsace.[105]

The cities of Strasbourg, Colmar, Basel, and Sélestat offered money to Sigismund of Austria to buy back Alsace from Charles; but Charles was determined to keep it and refused to sell.[106] To emphasize his claim, Charles toured the province around Christmas 1473, reportedly with an army.[107] He tried to make peace with the Swiss, who questioned his sincerity.[108] Charles's threats prompted the Swiss to ally themselves with their former enemy, Sigismund.[106]

In April 1474, the rebelling Alsatian cities and the Swiss formed the League of Constance to drive Charles and Peter von Hagenbach from Alsace,[108] and rebellion quickly broke out.[109] The league overthrew Hagenbach, put him on trial, and on 9 May executed him.[106] Upon hearing this news, Charles was enraged. In August, he sent an army led by Peter's brother, Stefan von Hagenbach, into Alsace.[110] After Charles refused again to give up control of Alsace, the League of Constance officially declared war on him.[111] Hagenbach's death might be considered the catalyst to the conflict now called the "Burgundian Wars".[110]

حصار نويس

When Alsace rose up against Burgundian authority, Charles was already preoccupied with another campaign, in Cologne.[111] Charles aided the Archbishop of Cologne, Ruprecht against a rebellion, hoping to turn the electorate into a Burgundian protectorate.[112] He held peace talks at Maastricht on 14 May 1474, which failed. From 22 June, he planned to lay siege to Colognian cities and force Ruprecht's subjects to accept the latter's terms.[113] The first of his targets was the city of Neuss, which Charles needed to control in order to guarantee Burgundian supply lines for an attack on Cologne. Neuss was expected to fall within a few days, and many contemporary historians feared its fall would open up Germany to the Burgundians.[113]

On 28 July 1474, Charles's army reached the southern gate of Neuss.[114] Its artillery immediately began bombardment to breach the walls.[115] To isolate the city, Charles assigned men to every gate, blockaded the river across Neuss with fifty boats, and secured the two isles adjacent to the city.[116] Despite all attempts, communications between Neuss and the outside world continued.[117] In September, the Burgundian night watch caught a man swimming in the river with a letter detailing Emperor Frederick's intention to attack the Burgundian besiegers.[118] Upon learning of Frederick's plan, Charles intensified the barrage, and attempted to drain the city's moat by diverting the River Erft and sinking overloaded barges into the Rhine.[118]

Residents of Neuss endured the constant bombardment, and refused to surrender even though their food had been reduced from cows to snails and weeds.[119] Their resistance gained admiration from all the contemporary chronicles.[120] Emperor Frederick was slow to amass an army. When he had gathered 20,000 German forces in Spring 1475, he took seventeen days to march from Cologne to Zons, their encampment.[121] Charles was constantly petitioned by his brother-in-law, Edward IV of England, to leave the siege and join Edward in fighting the French. But in the face of the Emperor's forces, Charles did not want to withdraw and lose face.[122] The Emperor had no desire to fight the Burgundians and limited his involvement in the conflict to a few skirmishes.[123] The conflict quickly came to an end after an emissary from the Pope threatened both sides with excommunication, and all parties signed a peace treaty on 29 May 1475.[124]

Charles left Neuss on 27 June.[125] The city had been so badly damaged that it was on the verge of surrender.[124] His propagandists presented him as the Caesar of their age who had brought a humiliating defeat on the German forces. After signing the peace treaty, hundreds of German soldiers lined up to see him. According to one chronicle, many of them threw themselves at Charles and worshipped him.[126] However, the Siege of Neuss cost Burgundy dearly in army strength and strategic opportunities.[125] Besides the number of men and equipment lost, this siege also cost Charles a chance to destroy Louis XI and France. Edward IV, after seeing no support from his ally, agreed to sign the Treaty of Picquigny with Louis XI; the terms of the treaty included a seven-year truce and a marriage alliance between the two kingdoms.[124] Charles had to sign a treaty with Louis as well, so that he would be free to march south and deal with the League of Constance, whose members now also included René II of Lorraine.[127]

معركة جراندسون

Charles commenced his full-fledged invasion against the Swiss and their allies immediately after signing the peace treaty with Louis XI. Splitting his army into two parts, he advanced through Lorraine with no resistance and captured the capital city of Nancy.[128] At the beginning of 1476, Charles besieged the recently captured castle of Grandson which was fortified by a garrison from Bern.[129] Despite the many relief forces sent to defeat the Burgundians, the Swiss were unable to relieve the city from the siege, and Charles recaptured Grandson, executing all of the Bernese garrison as retaliation for Swiss brutality in Burgundian towns.[130] On 1 March, Charles, expecting the Swiss army to march towards him for a battle, decided to leave Grandson and head northwards for a mountain pass north of the town of Concise. As he had foreseen, the Swiss army marched from Neuchâtel, with their vanguard, made up of eight thousand men, several hours ahead of the rest of their army. The vanguard reached the mountain pass first and surprised the Burgundian army.[131]

Charles quickly rallied his troops, ordered his artillery to fire at the enemy lines, and then launched an attack.[129] Meanwhile, the Swiss had knelt down to pray, which the Burgundians may have mistaken for submission, which only motivated the Burgundians more for the attack.[132] The initial charge, commanded by Louis de Châlon-Arlay, Lord of Grandson, failed to penetrate the Swiss defensive line, with Louis himself killed in the process.[132] Charles then made a second attack. In order to lure the enemy further down the valley to give his artillery a better target, Charles soon retreated.[133]

However, the rest of Charles's army mistook his tactical retreat for a complete withdrawal. Around this time, the rest of the Swiss army had reached the valley, announcing their arrival by bellowing their horns. The Burgundians panicked and abandoned their positions, ignoring Charles's pleas to stay in line.[134] The panicking army even forsook their camp at Grandson, leaving it for the Swiss to capture.[129][135] The Battle of Grandson became a humiliating defeat for Charles the Bold, as his army's cowardice had caused him the loss of many valuable treasures and all of his artillery and supplies.[136] For two or three days after the battle, Charles refused any food or drink. By 4 March, he began to reorganize his army in hopes of giving battle two weeks later.[137]

معركة مورا

Charles retreated to Lausanne, where he reorganised his army. He demanded more artillery and men-at-arms from his lands; in Dijon, anything made of metal was melted to make cannon; in occupied Lorraine, he confiscated all artillery.[138][ب] He received funds from all his allies, and men from Italy, Germany, England, and Poland came to join his army.[139] At the end of May, he had amassed 20,000 men in Lausanne, outnumbering the local population.[140] He trained these men from 14 to 26 May while he himself grew sicker by the day, resulting in stagnation among his troops. With the supply lines delayed, and the payment long overdue, Charles's army had to cut costs. Many horse archers went on foot instead. The army, though magnificent in appearance, was incohesive and unstable.[141]

On 27 May, Charles and his army began their slow march towards the fortress of Morat. His main objective was the city of Bern; to eliminate all support for the city, he first needed to conquer Morat.[139] He arrived at Morat on 9 June and immediately besieged the fortress. By 19 June, after several assaults on the fortress and with several of its walls destroyed, Morat sent a message to Bern, asking for help.[142] On 20 June, the Eidgenossen (oath companion[ت]) arrived at Morat.[145] The forces were larger than the army at Grandson; the Swiss commanders estimated themselves to be 30,000 men, while recent historians believe it was 24,000.[146] Charles expected a decisive battle in the wake of 21 June but no attack came.[145] The Swiss instead attacked the following day, 22 June, a holy day attributed to the Ten thousand martyrs, catching the slumbering Burgundians by surprise.[147] Charles was too slow in organizing his troops for a counterattack: he himself tarried in putting on his armour, and before his men finished taking their positions, the Swiss army had already reached them.[148] The Burgundian army soon abandoned their posts and fled for their lives.[149]

The battle was a total victory for the Swiss, and a slaughter of the fleeing Burgundian army ensued. Many retreated into Lake Morat and drowned. Some climbed the walnut trees, and were shot dead with arquebuses and hand cannons. The Swiss showed no mercy to men who surrendered. They killed knights, soldiers, and high officials alike.[150] Charles himself fled with his men and rode for days until he reached Gex, Ain.[151] The Milanese ambassador, Panigarola, reported that Charles laughed and made jokes after his defeat at Morat. He refused to believe he was defeated and continued to think God was on his side.[152]

وفاته في معركة نانسي

وبلغ الحزن بشارل أن أشرف على الجنون. فاغتنمت اللورين الفرصة ولانتقضت عليه، وأرسل السويسريون الرجال وبعث لويس الذهب لمعاونة الثورة. وألف شارل جيشاً جديداً، وحارب الحلفاء بالقرب من نانس، وهزم في المعركة ولقي الموت (1477). وفي الغداء التهمت الغيلان قطعاً من لحمه العاري، ووجد غارقاً إلى النصف في مستنقع، ووجهه متجمد ملتصق بالجليد. وكان الأربعة والأربعين من عمره. وهكذا اندمجت برجنديا في فرنسا.

ذكراه

Charles the Bold's untimely death directly led to the sudden collapse of the Burgundian State.[153] He had no legitimate male heir to succeed him and he did not provide a capable husband for his daughter that he could train and prepare for succession.[153] He was obsessed with uniting the "lands over there" (Low Countries) and the "lands over here" (Burgundy proper) through Lorraine,[11] and sought to forge a national identity independent from that of the French.[154] He spent his few years as the Duke of Burgundy in securing a crown and forging a new kingdom to unite his subjects, and to enhance his own glory.[155] However, his efforts inadvertently united his German enemies under the banner of a "German nation" opposing Charles, whom they called "The Grand Turk of the West".[156]

Charles's death marks a significant moment in the modern history of Lorraine;[157] in Nancy, the victory of René II is still remembered fondly.[158] The Swiss victory at Morat was a confirmation of their national identity, a mark of pride, and a preservation of their independence. The Battle of Morat contributed to the decline of feudalism and heralded the end to the concept of chivalry.[159] German-language historiography treats Charles ambivalently; he is seen both as a tragic representative of the fall of the Middle Ages, and as an immoral and flawed prince. Until recently, Swiss literature generally presented Charles negatively.[160]

Charles's death and the crisis of 1477 was an inspiration to two authors, Olivier de La Marche and Anthonis de Roovere, who wrote Le chevalier délibéré and Den droom van Rouere op die doot van hertoge Kaerle van Borgonnyen saleger gedachten,[ث] respectively, about his death.[162] The hatred between Charles the Bold and Louis XI was an inspiration for the 17th-century French moralistic dialogues by authors such as François Fénelon, who in his Dialogues of the dead portrays Charles and Louis reconciling by drinking from the River Styx.[163]

ملاحظات

- ^ Andreas inherited the claims to the Byzantine and Trebizond empires with the death of the main claimants from the empires' dynasties, Palaiologos and Komnenos, respectively.[22]

- ^ Philippe de Commines, the Burgundian chronicler, reported that in an official decree to all his realm, Charles ordered "Der Meyer zu Lockie an den Grafen zu Aarburg" (all the world to come to him with all (its) cannon and all (its) manpower).[138]

- ^ The word Eidgenossen is literary translated as 'oath companion', and was a synonym for the Swiss, referring to the members of the Old Swiss Confederacy.[143] Until the Siege of Morat, most of the confederacy had not declared war on Burgundy, because Charles had yet to invade a territory officially part of one of its members. But during the siege, Charles attacked a bridge which was a part of Bernese territory, thus obligating the confederacy to join Bern in their campaign against Burgundy.[144]

- ^ Translation: De Roovere's dream about the death of the late Charles of Burgundy.[161]

المراجع

- ^ Charles le Téméraire is more accurately translated in English as "the Rash", but the English speaking world generally refers to Charles as "the Bold". The history of Charles' epithets is complex: le Hardi (the Bold) may be Burgundian propaganda: far from being a nineteenth-century historians' appellation, he was already labelled Temerarius by the French in 1477. [1][dead link]

- ^ The title was derived from his savage behaviour against his enemies, and particularly from a war with France in late 1471: frustrated by the refusal of the French to engage in open battle, and angered by French attacks on his unprotected borders in Hainault and Flanders, Charles marched his army back from the Ile-de-France to Burgundian territory, burning more than 2000 towns, villages and castles on his way—Taylor, Aline S, Isabel of Burgundy, pp. 212–213

- ^ ديورانت, ول; ديورانت, أرييل. قصة الحضارة. ترجمة بقيادة زكي نجيب محمود.

- ^ Schnerb 2008, p. 451; Van Loo 2021

- ^ Vaughan & Paravicini 2002, pp. 186–187.

- ^ Van Loo 2021, p. 417.

- ^ Schepper 2007, p. 187.

- ^ أ ب ت Van Loo 2021, p. 418.

- ^ Golubeva 2013, p. 42.

- ^ Kontler & Somos 2017, p. 403.

- ^ أ ب Blockmans & Pervenier 1999, p. 193.

- ^ Vaughan & Paravicini 2002, p. 161.

- ^ Blockmans & Pervenier 1999, p. 185.

- ^ أ ب Schryver 2008, p. 16.

- ^ Schnitker 2004, p. 107.

- ^ Schryver 2008, p. 11.

- ^ Woodacre & McGlynn 2014, p. 115.

- ^ Walsh 1977, p. 53.

- ^ Jenks 2018, p. 215.

- ^ Vaughan & Paravicini 2002, p. 161; Walsh 1977, p. 68

- ^ Walsh 1977, p. 68.

- ^ أ ب Walsh 1977, p. 73.

- ^ Harris 1995, p. 539.

- ^ Graves 2014, p. 65.

- ^ أ ب ت Vaughan & Paravicini 2002, p. 180.

- ^ Vaughan & Paravicini 2002, pp. 73, 180.

- ^ Barany 2016, p. 88.

- ^ Barany 2016, p. 73.

- ^ Barany 2016, p. 74.

- ^ Vaughan & Paravicini 2002, p. 341.

- ^ Van Loo 2021, p. 409.

- ^ Waugh 2016, p. 256.

- ^ Smith & De Vries 2005, p. 165.

- ^ Kendall 1971, p. 248.

- ^ Smith & De Vries 2005, p. 170.

- ^ Vaughan & Paravicini 2002, p. 55.

- ^ Kendall 1971, p. 214.

- ^ Van Loo 2021, pp. 400–401.

- ^ Vaughan & Paravicini 2002, p. 56.

- ^ Vaughan & Paravicini 2002, p. 58.

- ^ Walsh 2005, p. 4.

- ^ Walsh 2005, p. 5.

- ^ Walsh 2005, p. 195.

- ^ D'Arcy & Dacre 2000, p. 403.

- ^ Walsh 2005, p. xx.

- ^ Walsh 2005, p. 303; Vaughan & Paravicini 2002, p. 165

- ^ Walsh 2005, p. 304.

- ^ Walsh 2005, p. 311.

- ^ Walsh 2005, p. 7.

- ^ Vaughan & Paravicini 2002, p. 75.

- ^ Walsh 2005, p. 35.

- ^ Walsh 2005, p. 8; Vaughan & Paravicini 2002, p. 304

- ^ Walsh 2005, p. 205.

- ^ Walsh 1977, p. 57.

- ^ Walsh 2005, p. 10.

- ^ Walsh 1977, p. 58.

- ^ Walsh 2005, p. 202.

- ^ Vaughan & Paravicini 2002, p. 216.

- ^ Walsh 2005, p. 16.

- ^ أ ب Walsh 2005, p. 13.

- ^ Vaughan & Paravicini 2002, p. 75; Walsh 2005, p. 13

- ^ Walsh 2005, p. 14.

- ^ Schnerb 2008, p. 444.

- ^ Walsh 2005, p. 280.

- ^ Gunn & Janse 2006, p. 156.

- ^ Gunn & Janse 2006, p. 157.

- ^ Gunn & Janse 2006, p. 158.

- ^ Kren & McKendrick 2003, p. 2.

- ^ Kren & McKendrick 2003, p. 223.

- ^ Kren & McKendrick 2003, p. 3.

- ^ Vaughan & Paravicini 2002, p. 163.

- ^ Hemelryck 2016.

- ^ Vaughan & Paravicini 2002, p. 164.

- ^ Schryver 2008, p. 12.

- ^ Ainsworth 1998, p. 25.

- ^ Fallows 2019, p. 3.

- ^ Brown 1999, p. 54.

- ^ Alden 2010, p. 135.

- ^ Blockmans & Pervenier 1999, p. 228.

- ^ Wright & Fallows 2001.

- ^ Taruskin 2009, p. 485.

- ^ Fallows 2019, p. 4.

- ^ Fallows 2019, p. 12.

- ^ Fallows 2019, pp. 12–18.

- ^ Vaughan & Paravicini 2002, p. 162.

- ^ Lecuppre-Desjardin 2022, pp. 203–204.

- ^ Allmand 2001, p. 142.

- ^ Vaughan & Paravicini 2002, p. 205.

- ^ Smith & De Vries 2005, p. 171.

- ^ Querengässer 2021, p. 102.

- ^ أ ب Smith & De Vries 2005, p. 172.

- ^ أ ب ت Drake 2013, p. 224.

- ^ Vaughan & Paravicini 2002, p. 209.

- ^ Vaughan & Paravicini 2002, p. 225.

- ^ Van Loo 2021, p. 420.

- ^ Allmand 2001, p. 137.

- ^ Drake 2013, p. 223.

- ^ Allmand 2001, pp. 138, 140.

- ^ Allmand 2001, p. 138.

- ^ Vaughan & Paravicini 2002, p. 214.

- ^ أ ب Smith & De Vries 2005, p. 173.

- ^ Baboukis 2010b, p. 367.

- ^ Walsh 2005, p. 341.

- ^ Golubeva 2013, p. 32.

- ^ Vaughan & Paravicini 2002, p. 273.

- ^ أ ب ت Van Loo 2021, p. 429.

- ^ Vaughan & Paravicini 2002, p. 276.

- ^ أ ب Smith & De Vries 2005, p. 174.

- ^ Knecht 2007, p. 98.

- ^ أ ب Simpson & Heller 2013, p. 37.

- ^ أ ب Van Loo 2021, p. 430.

- ^ Van Loo 2021, p. 428.

- ^ أ ب Williams 2014, p. 22.

- ^ Williams 2014, p. 23.

- ^ Villalon & Kagay 2005, p. 445.

- ^ Williams 2014, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Smith & De Vries 2005, p. 48.

- ^ أ ب Williams 2014, p. 24.

- ^ Van Loo 2021, p. 431.

- ^ Smith & De Vries 2005, p. 180.

- ^ Smith & De Vries 2005, p. 182.

- ^ Williams 2014, p. 25.

- ^ Smith & De Vries 2005; Van Loo 2021

- ^ أ ب ت Williams 2014, p. 26.

- ^ أ ب Smith & De Vries 2005, p. 183.

- ^ Van Loo 2021, p. 432.

- ^ Smith & De Vries 2005, p. 184.

- ^ Smith & De Vries 2005, p. 185.

- ^ أ ب ت Baboukis 2010c.

- ^ Beazley 2014, p. 28.

- ^ Beazley 2014; Baboukis 2010c

- ^ أ ب Beazley 2014, p. 29.

- ^ Van Loo 2021, p. 437.

- ^ Beazley 2014; Baboukis 2010c

- ^ Van Loo 2021, p. 438.

- ^ Beazley 2014, p. 33.

- ^ Vaughan & Paravicini 2002, p. 378.

- ^ أ ب Winkler 2010, p. 20.

- ^ أ ب Winkler 2010, p. 21.

- ^ Van Loo 2021, p. 439.

- ^ Brunner 2011, p. 47.

- ^ Winkler 2010, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Vaughan & Paravicini 2002, p. 263.

- ^ Brunner 2011, p. 48.

- ^ أ ب Van Loo 2021, p. 443.

- ^ Winkler 2010, p. 26.

- ^ Winkler 2010, p. 27.

- ^ Winkler 2010, p. 29.

- ^ Van Loo 2021, p. 444.

- ^ Winkler 2010, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Winkler 2010, p. 33.

- ^ Smith & De Vries 2005, p. 197.

- ^ أ ب Vaughan & Paravicini 2002, p. 399.

- ^ Lecuppre-Desjardin 2022, p. 337.

- ^ Lecuppre-Desjardin 2022, p. 157.

- ^ Lecuppre-Desjardin 2022, p. 217.

- ^ Monter 2007, p. 15.

- ^ Monter 2007, p. 22.

- ^ Winkler 2010, p. 34.

- ^ Sieber-Lehmann 1997, p. 13.

- ^ Jongenelen & Parsons 2016, p. 306.

- ^ Jongenelen & Parsons 2016, p. 306-307.

- ^ Bakos 2013, p. 50.

أسلافه

| شارل الجسور | والده: فليپ الطيب |

جده لوالده: جون الشجاع |

جده الأكبر لوالده: فليپ الجسور |

| جدته الكبرى لوالده: مارگريت الثالثة، كونتسة فلاندرز | |||

| جدته لوالده: مارگريت من باڤاريا |

والد جده الأكبر لوالده: ألبير الأول، دوق باڤاريا | ||

| جدته الكبرى لوالدته: مارگريت من بريگ | |||

| والدته: إزابيلا من الپرتغال |

جده الأكبر لوالدته: جون الأول من الپرتغال |

والد جده الأكبر لوالدته: پدرو الأول من الپرتغال | |

| والد جدته الكبرى لوالدته: تريزا گيل لورنسو | |||

| جدته لوالدته: فليپا من لانكستر |

جده الأكبر لوالدته: جون من گونت، دوق أول لانكستر | ||

| والدة جدته الكبرى لوالدته: بلانش من لانكستر |

الألقاب

1433–5 يناير 1477: كونت كارولياس باسم شارل الأول

1433–5 يناير 1477: كونت كارولياس باسم شارل الأول 15 يونيو 1467–5 يناير 1477: دوق برگندي باسم شارل الأول

15 يونيو 1467–5 يناير 1477: دوق برگندي باسم شارل الأول- 15 يونيو 1467–5 يناير 1477: Duke of Brabant باسم شارل الأول

15 يونيو 1467–5 يناير 1477: دوق لوميبورگ باسم شارل الأول

15 يونيو 1467–5 يناير 1477: دوق لوميبورگ باسم شارل الأول 15 يونيو 1467–5 يناير 1477: دوق لوثييه باسم شارل الأول

15 يونيو 1467–5 يناير 1477: دوق لوثييه باسم شارل الأول 15 يونيو 1467–5 يناير 1477: دوق لوكسمبورگ باسم شارل الثاني

15 يونيو 1467–5 يناير 1477: دوق لوكسمبورگ باسم شارل الثاني 15 يونيو 1467–5 يناير 1477: مارگراڤه نامور باسم شارل الأول

15 يونيو 1467–5 يناير 1477: مارگراڤه نامور باسم شارل الأول 15 يونيو 1467–5 يناير 1477: كونت پالتين برگندي باسم شارل الأول

15 يونيو 1467–5 يناير 1477: كونت پالتين برگندي باسم شارل الأول 15 يونيو 1467–5 يناير 1477: كونت أرتوا باسم شارل الأول

15 يونيو 1467–5 يناير 1477: كونت أرتوا باسم شارل الأول 15 يونيو 1467–5 يناير 1477: كونت فلاندرز باسم شارل الثاني

15 يونيو 1467–5 يناير 1477: كونت فلاندرز باسم شارل الثاني 15 يونيو 1467–5 يناير 1477: Count of Hainault باسم Charles I

15 يونيو 1467–5 يناير 1477: Count of Hainault باسم Charles I 15 يونيو 1467–5 يناير 1477: Count of Holland باسم شارل الأول

15 يونيو 1467–5 يناير 1477: Count of Holland باسم شارل الأول15 يونيو 1467–5 يناير 1477: Count of Zeeland باسم شارل الأول

23 فبراير 1473–5 يناير 1477: Duke of Guelders باسم شارل الأول

23 فبراير 1473–5 يناير 1477: Duke of Guelders باسم شارل الأول 23 فبراير 1473–5 يناير 1477: Count of Zutphen باسم شارل الأول

23 فبراير 1473–5 يناير 1477: Count of Zutphen باسم شارل الأول

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

المراجع

- تحوي هذه المقالة معلومات مترجمة من الطبعة الحادية عشرة لدائرة المعارف البريطانية لسنة 1911 وهي الآن من ضمن الملكية العامة.

هذه المقالة تضم نصاً من مطبوعة هي الآن مشاع: هربرمان, تشارلز, ed. (1913). . الموسوعة الكاثوليكية. Robert Appleton Company.

هذه المقالة تضم نصاً من مطبوعة هي الآن مشاع: هربرمان, تشارلز, ed. (1913). . الموسوعة الكاثوليكية. Robert Appleton Company. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|1=,|coauthors=, and|month=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)- Taylor, Aline S. Isabel of Burgundy.

قراءات إضافية

- Vaughan, Richard (1973), Charles the Bold: The Last Valois Duke of Burgundy, London: Longman Group, ISBN 0-582-50251-9.

شارل الجسور فرع أصغر من آل كاپيتان وُلِد: 10 نوفمبر 1433 توفي: 5 يناير 1477

| ||

| سبقه فليپ الطيب |

Duke of Burgundy, Brabant, Limburg, Lothier and Luxemburg; Margrave of Namur; Count of Artois, Flanders, Hainaut, Holland and Zeeland; Count Palatine of Burgundy 15 يوليو 1467 – 5 يناير 1477 |

تبعه ماري |

| Count of Charolais أغسطس 1433 – 5 يناير 1477 | ||

| سبقه أرنولد |

دوق گلدرز كونت زوتفن 23 فبراير 1473 – 5 يناير1477 | |

- Articles with dead external links from April 2012

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing فرنسية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing هولندية-language text

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages with empty portal template

- مقالات مأخوذة من الطبعة الحادية عشرة لدائرة المعارف البريطانية

- Articles incorporating text from the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia with Wikisource reference

- مواليد 1433

- وفيات 1477

- أشخاص من ديجون

- بيت ڤالوا-برگندي

- دوقات برگندي

- Dukes of Brabant

- Dukes of Lothier

- Dukes of Guelders

- Dukes of Limburg

- دوقات لوكسمبورگ

- دوقات فلاندرز

- Counts of Artois

- كونتات برگندي

- Counts of Hainaut

- Counts of Holland

- Counts of Zeeland

- Counts of Charolais

- Margraves of Namur

- فرسان الوبر الذهبي

- عسكريون قتلوا في المعركة

- Grand Masters of the Order of the Golden Fleece

- Extra Knights Companion of the Garter