تاريخ اليهود في ألمانيا

The location of Germany (dark green) in the European Union (light green) | |

| إجمالي التعداد | |

|---|---|

| 116,000 to 225,000[1] | |

| المناطق ذات التجمعات المعتبرة | |

| Germany Israel, United States, Chile, Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, and the United Kingdom | |

| اللغات | |

| English, German, Russian, Hebrew, other immigrant languages, Yiddish | |

| الدين | |

| Judaism, agnosticism, atheism or other religions | |

| الجماعات العرقية ذات الصلة | |

| Other Ashkenazi Jews, Sephardi Jews, Mizrahi Jews, Israelis |

| جزء من سلسلة مقالات عن |

| اليهود و اليهودية |

|---|

|

| من هو اليهودي؟ • أصل الكلمة • الثقافة |

بدأ تواجد اليهود في ألمانيا في أوائل القرن الرابع. بدأ ظهور الجماعات اليهودية تحت شارلمان، لكنه عانى أثناء الحملات الصليبية. (تواجد اليهود الألمان أيضاً في صورة اليهود الأشكناز في العصر المظلمة والعصور الوسطى.) ادعاءات تسميم الآبار أثناء الموت الأسود (1346-53) إلى ارتكاب مجازر جماعية لليهود الألمان[بحاجة لمصدر]، وإلى فرار أعداد كبيرة منهم إلى پولندا.

من عهد موسى مندلسون حتى القرن العشرين تحررت الجماعة اليهودية بالتدريج، ثم ازدهرت. ومع ذلك، ففي أعقاب نمو النازية وأيديولوجيتها وسياساتها المعادية للسامية، عانى اليهود من الاضهاد وتعرضوا للتطهير العرقي. هاجر معظم اليهود، حيث كانت أعداد اليهود المقيمين في ألمانيا تصل إلى 522.000 يهودي في يناير 1833، تبقى منهم في بداية الحرب العالمية الثانية حوالي 214.000 يهودي فقد. حوالي 90% من الجماعات المتبقية قُتلت أثناء الحرب.[2]

بعد الحرب بدأت الجماعات اليهودية في التزايد مرة ثانية بالتجريد، ويرجع ذلك بصفة رئيسية إلى المهاجرين القادمين من الاتحاد السوڤيتي السابق. بحلول القرن 21، وصل عدد اليهود في ألمانيا إلى 200.000 وتعتبر ألمانيا هي البلد الأوروپي الوحيد التي يتزايد فيها أعداد اليهود.[3]

من روما إلى الحملات الصليبية

Jewish migration from Roman Italy is considered the most likely source of the first Jews on German territory. There were Jews in Rome as early as 139 BCE.[4] While the date of the first settlement of Jews in the regions which the Romans called Germania Superior, Germania Inferior, and Magna Germania is not known, the first authentic document relating to a large and well-organized Jewish community in these regions dates from 321 CE[5][6][7][8] and refers to Cologne on the Rhine.[9][10][11] It indicates that the legal status of the Jews there was the same as elsewhere in the Roman Empire. They enjoyed some civil liberties, but were restricted regarding the dissemination of their culture, the keeping of non-Jewish slaves, and the holding of office under the government.

Jews were otherwise free to follow any occupation open to indigenous Germans and were engaged in agriculture, trade, industry, and gradually money-lending. These conditions at first continued in the subsequently established Germanic kingdoms under the Burgundians and Franks, for ecclesiasticism took root slowly. The Merovingian rulers who succeeded to the Burgundian empire were devoid of fanaticism and gave scant support to the efforts of the Church to restrict the civic and social status of the Jews.

Charlemagne (800–814) readily made use of the Roman Catholic Church for the purpose of infusing coherence into the loosely joined parts of his extensive empire, but was not by any means a blind tool of the canonical law. He employed Jews for diplomatic purposes, sending, for instance, a Jew as interpreter and guide with his embassy to Harun al-Rashid.[12] Yet, even then, a gradual change occurred in the lives of the Jews. The Church forbade Christians to be usurers, so the Jews secured the remunerative monopoly of money-lending. This decree caused a mixed reaction of people in general in the Carolingian Empire (including Germany) to the Jews: Jewish people were sought everywhere, as well as avoided. This ambivalence about Jews occurred because their capital was indispensable, while their business was viewed as disreputable. This curious combination of circumstances increased Jewish influence, and Jews went about the country freely, settling also in the eastern portions (Old Saxony and Duchy of Thuringia). Aside from Cologne, where an 8th century mikveh exists, the earliest communities were established in Mainz, Worms, Speyer, Regensburg, and Aachen.[13]

The status of the German Jews remained unchanged under Charlemagne's successor, Louis the Pious. Jews were unrestricted in their commerce; however, they paid somewhat higher taxes into the state treasury than did the non-Jews. A special officer, the Judenmeister, was appointed by the government to protect Jewish privileges. The later Carolingians, however, followed the demands of the Church more and more. The bishops continually argued at the synods for including and enforcing decrees of the canonical law, with the consequence that the majority Christian populace mistrusted the Jewish populace. This feeling, among both princes and people, was further stimulated by the attacks on the civic equality of the Jews. Beginning with the 10th century, Holy Week became more and more a period of antisemitic activities. Jews in Germany could read and understand the Hebrew prayers and the Bible in the original text. Halakhic studies began to flourish about 1000.

At that time, Rav Gershom ben Judah was teaching at Metz and Mainz, gathering about him pupils from far and near. He is described in Jewish historiography as a model of wisdom, humility, and piety, and became known to succeeding generations as the "Light of the Exile".[14] In highlighting his role in the religious development of Jews in the German lands, The Jewish Encyclopedia (1901–1906) draws a direct connection to the great spiritual fortitude later shown by the Jewish communities in the era of the Crusades:

He first stimulated the German Jews to study the treasures of their religious literature. This continuous study of the Torah and the Talmud produced such a devotion to Judaism that the Jews considered life without their religion not worth living; but they did not realize this clearly until the time of the Crusades, when they were often compelled to choose between life and faith.[15]

المركز الثقافي والديني ليهود أوروبا

| موقع تراث عالمي حسب اليونسكو | |

|---|---|

| |

| السمات | Cultural: ii, iii, vi |

| مراجع | 1636 |

| التدوين | 2021 (45 Session) |

| موقع إلكتروني | Official website |

يعود استقرار بعض أعضاء الجماعات اليهودية في ألمانيا إلى الحملات الرومانية، وكوَّنت الجماعات اليهودية الأولى جزءاً من المـدن الرومانية العسـكرية على نهري الراين والدانوب (وڤورمز وشپير). وكان أول وأهم هذه المعسكرات معسكر كولونيا (وهي من كلمة لاتينية تعني مستعمرة، وكلمة «كولونيالية» أي «استعمار» مشتقة من الكلمة نفسها). ثم استوطن يهود آخرون في ألمانيا أثناء حكم شارلمان والإمبراطورية الكارولنجية. ويَرد في القرن العاشر الميلادي ذكر تجمعات يهودية في مدن مثل كولون. كما كانت تُوجَد تجمعات في أوجسبرج وورمز ومينز.

وقد كان أعضاء الجماعات اليهودية إبّان حكم الإمبراطورية الكارولنجية تحت حماية الإمبراطور، يتبعونه ويقدم هو لهم المواثيق والحماية والمزايا. وكانت علاقة الكنيسة بهم، وخصوصاً الأساقفة، طيبة على وجه العموم. وكان لليهود رئيسهم الديني الدنيوي الذي كان يُسمَّى «الآرش سينا جوجوس» أو رئيس المعبد، كما كان يُطلَق عليه «ابيسكوبوس جيود وروم» أو «أسقف اليهود».

وأثناء حملة الفرنجة الأولى قام الأساقفة والملوك بحماية أعضاء الجماعات اليهودية من السخط الشعبي عليهم، فأصدر هنري الرابع عدة مواثيق عام 1090 تؤكد الحقوق التي حصلوا عليها في العصر الكارولينجي بشأن حماية ممتلكاتهم وأرواحهم والتي تؤكد أيضاً حرية السفر والعبادة بالنسبة لهم. وكان أعضاء الجماعات اليهودية مُعْفَيْنَ من المكوس والضرائب التي تُفرَض على المسافرين، وكان لهم حق التقاضي فيما بينهم وحق الفصل في الأمور اليهودية المختلفة مثل الزواج والطلاق والتعليم، أي كانت لهم إدارتهم الذاتية. وسُمح لهم بالاستمرار في تجارة الرقيق وأن يقيموا في أماكن خاصة بهم كما هو الحال مع الغرباء كافة. وعادةً ما كانت هذه الأماكن في أحسن موقع بالمدن على الشارع الرئيسي أو بجوار الكوبري الذي يؤدي إلى المدينة والذي يمثل عصبها التجاري. وكان أعضاء الجماعات اليهودية يُعَدُّون عنصراً بالغ الفائدة والنفع للحكام والأمراء والأساقفة والأباطرة. ويظهر ذلك عام 1084 في واحدة من أولى الوثائق التي ضمنت لليهود حقوقهم وامتيازاتهم، وهي خطاب الأسقف الأمير حاكم سبير، الذي دعا اليهود إلى الاستيطان في مدينته كجماعة وظيفية استيطانية، حتى يمكنه أن يحوِّلها من قرية إلى مدينة وأن يخرجها من الاقتصاد الزراعي ويدخلها الاقتصاد التجاري. وأُعطي اليهود الحق في أن يتحصنوا داخل المدينة منعاً لأية هجمات قد تقع عليهم. وحينما اندلعت الاضطرابات ضد أعضاء الجماعة، إبّان حملة الفرنجة، أرسلوا إلى هنري الرابع الذي كان في زيارة إلى إيطاليا، فأصدر أمره إلى الأدواق والأساقفة في ألمانيا بحمايتهم. ومع هذا، استمرت الاضطرابات، وذبح المتظاهرون أحد عشر يهودياً في سبتمبر 1096، فتدخَّل الأسقف واتخذ إجراءات مضادة. ويُقال إن عدد اليهود الذين ذُبحوا في ألمانيا أساساً، وكذلك في غيرها من بلاد أوربا إبّان هذه الحملة، بلغ اثنى عشر ألف يهودي. وهو عدد مُبالَغ فيه. وحينما عاد هنري الرابع من إيطاليا، سُمح لليهود الذين تنصروا عنوة بالعودة إلى دينهم، وأمر بمعاقبة أحد الأساقفة ممن صادروا ممتلكاتهم. كما أصدر قراراً عام 1103 بأن عقوبة الهجوم على أعضاء الجماعات اليهودية أو ممتلكاتهم هي الإعدام، وأن هدنة الرب التي أُعلنت في ذلك الوقت تنطبق على اليهود انطباقها على المسيحيين، وأن اليهود يتمتعون بالحماية نفسها التي يتمتع بها القساوسة.

ولا يُعرَف عدد يهود ألمانيا في هذه الفترة على وجه الدقة، ولكن من المعروف أن بعض الجماعات كان يصل عددها إلى ألفين وأنهم تركزوا أساساً على الشاطئ الغربي لنهر الراين في منطقة اللورين، وفي المراكز التجارية مثل كولونيا وماينز وشپاير وڤورمز، وفي المراكز الدينية والسياسية المسيحية مثل پراگ. وكانوا يعملون أساساً بالتجارة الدولية، ولكنهم بدأوا في هذه الفترة بالعمل في الربا أيضاً. وتمكنت السلطات الحاكمة من حماية اليهود إبّان حملة الفرنجة الثانية.

وأصبحت حماية أعضاء الجماعة اليهودية جزءاً من القانون العام، فنعموا بشيء من السلام تحت حماية الإمبراطور، ومنح فريدريك الأول اليهود ميثاقاً لحماية إحدى الجماعات اليهودية عام 1157 استُخدم فيه مصطلح «أقنان بلاط» لأول مرة (وإن كان المفهوم قد ظهر قبل ذلك التاريخ). وأدَّى هذا الوضع إلى ازدياد التصاق أعضاء الجماعة اليهودية بالسلطة الحاكمة. ولكن حمايتهم بشكل كامل لم تكن أمراً ممكناً لأن العداوة ضدهم كانت مسألة متأصلة ذات طابع جماهيري عام، فاليهودي هو الممثل المباشر الواضح للسلطة، كما أن إبهام وضعه جعل منه فريسة سهلة. وهو إلى جانب ذلك يقطن بين الجماهير ويتحرك بينها (على عكس أعضاء الأرستقراطية). ومن ثم، كان اليهودي أضعف الحلقات في سلسلة القمع. وقد اشتغل أعضاء الجماعة اليهودية بالربا، وحدد مرسوم الدوق فريدريك الثاني في النمسا عام 1244 الفائدة على القروض بنحو 173.5%. وكانت القروض تُمنَح بضمان رهونات يستولى عليها المرابي عند فشل المدين في الدفع، الأمر الذي جعل الجـماهير تتهمـهم بامتصاص دم الشـعب، ومن هنا جـاءت تهمة الدم. ولم يكن حق المرابي يسقط في السلعة المرهونة لديه إن ثبت أنها مسروقة، شريطة أن يثبت أنه لم يكن يعرف أنها مسروقة، مع أن هذا مناف للقانون الألماني. ومن ثم، ارتبط أعضاء الجماعة اليهودية باللصوص والتجارة غير الشرعية.

وظهرت في هذه الفترة بيوتات المال الإيطالية والقوى التجارية المحلية التي زاحمت اليهود. فبدأ وضعهم في التدهور، وخصوصاً أن الكنيسة بدأت هي الأخرى في محاربة "المرض اليهودي"، أي الربا. وعُقد المجمع اللاتراني الرابع عام 1215، وهو المجلس الذي حرَّم الربا وفرض على اليهود ارتداء زي خاص بهم وتعليق الشارة اليهودية.

فترة المذابح (1096–1349)

ومع بداية الحملة الثالثة من حملات الفرنجة، بدأ التهييج ضد أعضاء الجماعة اليهودية. فبذل فريدريك الأول قصارى جهده لوقف الثورة الشعبية، وأعلن أن جريمة قتل اليهودي عقوبتها الإعدام، أما إلحاق الأذي به فعقوبته قطع الذراع.

وأخذ الاحتجاج الشعبي شكل تهمة الدم واتهام اليهود بتسميم الآبار. أما تهمة الدم، فهي ولا شك تعبير عن إحساس الجماهير بأن اليهود يمتصون دم ضحاياهم، أي ثروتهم. أما تسميم الآبار، فعلَّق عليها أحد المؤرخين المعاصرين بقوله: « إن السم اليهودي الحقيقي هو ثروتهم »، وهو ما يبيِّن الطابع الشعبوي لهذه الاتهامات. ولعبت الكنيسة دوراً مهماً في حماية اليهود، كما قام الإمبراطور فريدريك الثاني بالتحقيق في إحدى تهم الدم المنسوبة لأعضاء الجماعة اليهودية، وأصدر عام 1236 حكماً ببراءة المتهمين، وأُلحق بحكم البراءة قراراً يجدد الحقوق الممنوحة لليهود بمقتضى قرارات هنري الرابع. ولم يكن القرار يشير إلى يهود إمارة أو اثنتين وإنما كان يشير إلى يهود ألمانيا كافة باعتبارهم أقنان بلاط. وهذا يعني أن اليهود، وكل ما يملكون، أصبحوا من الناحية القانونية ملكاً للإمبراطور وغير خاضعين لأية سلطة أخرى داخل المجتمع. ولخَّص أحد اليهود وضع اليهود كعنصر مالي تجاري حر تابع للإمبراطور بقوله: "إن اليهود غير مرتبطين بأي مكان خاص مثل غير اليهود، وهم فقراء ولكنهم مع هذا لا يباعون كعبيد". ويظهر مدى نفع اليهود في أنهم ساهموا بما يزيد على 12% من دخل الخزانة الإمبراطورية كله عام 1238، و20% من الضرائب التي حصلت في المدن الألمانية، وذلك رغم قلة أعدادهم، إذ كانوا لا يزيدون على 1% أو أقل من مجموع السكان.

في الامبراطورية الرومانية المقدسة

Arriving from France and Spain, the legal and civic status of the Jews underwent a transformation under the Holy Roman Empire. Jewish people found a certain degree of protection with the Holy Roman Emperor, who claimed the right of possession and protection of all the Jews of the empire. A justification for this claim was that the Holy Roman Emperor was the successor of the emperor Titus, who was said to have acquired the Jews as his private property. The German emperors apparently claimed this right of possession more for the sake of taxing the Jews than of protecting them.

A variety of such taxes existed. Louis IV, Holy Roman Emperor, was a prolific creator of new taxes. In 1342, he instituted the "golden sacrificial penny" and decreed that every year all the Jews should pay the emperor one kreutzer out of every florins of their property in addition to the taxes they were already paying to both the state and municipal authorities. The emperors of the House of Luxembourg devised other means of taxation. They turned their prerogatives in regard to the Jews to further account by selling at a high price to the princes and free towns of the empire the valuable privilege of taxing and fining the Jews. Charles IV, via the Golden Bull of 1356, granted this privilege to the seven electors of the empire when the empire was reorganized in 1356.

From this time onward, for reasons that also apparently concerned taxes, the Jews of Germany gradually passed in increasing numbers from the authority of the emperor to that of both the lesser sovereigns and the cities. For the sake of sorely needed revenue, the Jews were now invited, with the promise of full protection, to return to those districts and cities from which they had shortly before been expelled. However, as soon as Jewish people acquired some property, they were again plundered and driven away. These episodes thenceforth constituted a large portion of the medieval history of the German Jews (and also elsewhere in Europe). Emperor Wenceslaus was particularly skilled at transferring gold from wealthier Jews to his own coffers. He entered compacts with many cities, estates, and princes whereby he annulled all outstanding debts to the Jews in return for a certain sum paid to him. Emperor Wenceslaus declared that anyone helping Jews with the collection of their debts, in spite of this annulment, would be dealt with as a robber and peacebreaker, and be forced to make restitution. This decree, which is believed to have impaired the public availability of credit was also reported to have impoverished thousands of Jewish families near the close of the 14th century.

The 15th century did not bring any amelioration. What happened in the time of the Crusades happened again. The war upon the Hussites became the signal for renewed persecution of Jews. The Jews of Austria, Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia passed through all the terrors of death, forced baptism, or voluntary self-immolation for the sake of their faith. When the Hussites made peace with the Church, the Pope sent the Franciscan friar John of Capistrano to win the renegades back into the fold and inspire them with loathing for "heresy" and "unbelief"; 41 heretics were burned in Wrocław alone, and all Jews were forever banished from Silesia. The Franciscan friar Bernardine of Feltre brought a similar fate upon the communities in southern and western Germany. As a consequence of the fictitious confessions extracted under torture from the Jews of Trent, the populace of many cities, especially of Regensburg, fell upon the Jews and massacred them.

The end of the 15th century, which brought a new epoch for the Christian world, brought no relief to the Jews. Jews in Germany remained the victims of a religious hatred that ascribed to them all possible evils. When the established Church, threatened in its spiritual power in Germany and elsewhere, prepared for its conflict with the culture of the German Renaissance, one of its most convenient points of attack was rabbinic literature. At this time, as once before in France, Jewish converts spread false reports in regard to the Talmud, but an advocate of the book arose in the person of Johann Reuchlin, the German humanist, who was the first one in Germany to include the Hebrew language among the humanities. His opinion, though strongly opposed by the Dominicans and their followers, finally prevailed when the humanistic Pope Leo X permitted the Talmud to be printed in Italy.

موزس مندلسون

Though reading German books was forbidden in the 1700s by Jewish inspectors who had a measure of police power in Germany, Moses Mendelson found his first German book, an edition of Protestant theology, at a well-organized system of Jewish charity for needy Talmud students. Mendelssohn read this book and found proof of the existence of God – his first meeting with a sample of European letters. This was only the beginning to Mendelssohn's inquiries about the knowledge of life. Mendelssohn learned many new languages, and with his whole education consisting of Talmud lessons, he thought in Hebrew and translated for himself every new piece of work he met into this language. The divide between the Jews and the rest of society was caused by a lack of translation between these two languages, and Mendelssohn translated the Torah into German, bridging the gap between the two; this book allowed Jews to speak and write in German, preparing them for participation in German culture and secular science. In 1750, Mendelssohn began to serve as a teacher in the house of Isaac Bernhard, the owner of a silk factory, after beginning his publications of philosophical essays in German. Mendelssohn conceived of God as a perfect Being and had faith in "God's wisdom, righteousness, mercy, and goodness." He argued, "the world results from a creative act through which the divine will seeks to realize the highest good," and accepted the existence of miracles and revelation as long as belief in God did not depend on them. He also believed that revelation could not contradict reason. Like the deists, Mendelssohn claimed that reason could discover the reality of God, divine providence, and immortality of the soul. He was the first to speak out against the use of excommunication as a religious threat. At the height of his career, in 1769, Mendelssohn was publicly challenged by a Christian apologist, a Zurich pastor named John Lavater, to defend the superiority of Judaism over Christianity. From then on, he was involved in defending Judaism in print. In 1783, he published Jerusalem, or On Religious Power and Judaism. Speculating that no religious institution should use coercion and emphasized that Judaism does not coerce the mind through dogma, he argued that through reason, all people could discover religious philosophical truths, but what made Judaism unique was its revealed code of legal, ritual, and moral law. He said that Jews must live in civil society, but only in a way that their right to observe religious laws is granted, while also recognizing the needs for respect, and multiplicity of religions. He campaigned for emancipation and instructed Jews to form bonds with the gentile governments, attempting to improve the relationship between Jews and Christians while arguing for tolerance and humanity. He became the symbol of the Jewish Enlightenment, the Haskalah.[16]

مطلع القرن التاسع عشر

ومع بدايات القرن الثامن عشر، وظهور جهاز الدولة القوي، لم تَعُد هناك حاجة إلى يهود البلاط ولا إلى الجماعات اليهودية كجماعة وظيفية وسيطة. وبدأت محاولات ضبط اليهود وتحديثهم، فأصدرت الدويلات الألمانية المطلقة، وبروسيا، نظماً مختلفة للإشراف على اليهود لتنظيم سائر تفاصيل حياتهم ولاستغلالهم. وكانت هذه القوانين تنظم حقوقهم وامتيازاتهم كما تحدد دخولهم، ومدى أحقيتهم في الاستيطان، ومدة بقائهم، وعدد الزيجات التي يمكن أن تتم، وعدد الأطفال المصرح لهم بإنجابهم، ومسائل الوراثة وطرق إدارة الأعمال، وسلوكهم، وضرائبهم، وحتى السلع التي يحق لهم شراؤها. ولعل القوانين التي صدرت في بروسيا هي خير مثل على ذلك، إذ تم تقسيم أعضاء الجماعة حسـب مرسـوم فريدريك الثاني (الأكبر)، الصـادر عـام 1750، إلى أقسام حسب وضعهم في المجتمع. وكانت أعلى الطبقات طبقة اليهود المتميِّزين بشكل عام الذين يتمتعون بكل الحقوق التي يتمتع بها المواطنون، تليها طبقة المتمتعين بحماية عامة، وهؤلاء كانوا يتمتعون بكثير من الحقوق ولكنهم لم يكن من حقهم توريثها إلا للابن الأكبر دون بقية الأولاد، ثم طبقة اليهود المتمتعين بحماية خاصة ولا يمكنهم توريث حقوقهم لأحد. أما اليهود الذين كانوا يتمتعون بتسامح الدولة، فكان لا يُسمح لهم بالزواج وكان عليهم ترك بروسيا عند رغبتهم في الزواج.

وبدأت الدويـلات الألمانية في تلك المرحلة محاولة دمج وتحديث أعضاء الجماعة اليهودية، فأصدر فريدريك الأكبر ميثاقاً يضمن لهم حق العبادة. وشجع كثير من الإمارات أعضاء الجماعات اليهودية، وخصوصاً المارانو، على الاستيطان فيها لتنشيط التجار. وصاحب ذلك استصدار قوانين تحمي حقوقهم الاقتصادية والسياسية والدينية.

In the late 18th century, a youthful enthusiasm for new ideals of religious equality began to take hold in the western world. Austrian Emperor Joseph II was foremost in espousing these new ideals. As early as 1782, he issued the Patent of Toleration for the Jews of Lower Austria, thereby establishing civic equality for his Jewish subjects.

Before 1806, when general citizenship was largely nonexistent in the Holy Roman Empire, its inhabitants were subject to varying estate regulations. In different ways from one territory of the empire to another, these regulations classified inhabitants into different groups, such as dynasts, members of the court entourage, other aristocrats, city dwellers (burghers), Jews, Huguenots (in Prussia a special estate until 1810), free peasants, serfs, peddlers and Gypsies, with different privileges and burdens attached to each classification. Legal inequality was the principle.

The concept of citizenship was mostly restricted to cities, especially Free Imperial Cities. No general franchise existed, which remained a privilege for the few, who had inherited the status or acquired it when they reached a certain level of taxed income or could afford the expense of the citizen's fee (Bürgergeld). Citizenship was often further restricted to city dwellers affiliated to the locally dominant Christian denomination (Calvinism, Roman Catholicism, or Lutheranism). City dwellers of other denominations or religions and those who lacked the necessary wealth to qualify as citizens were considered to be mere inhabitants who lacked political rights, and were sometimes subject to revocable residence permits.

Most Jews then living in those parts of Germany that allowed them to settle were automatically defined as mere indigenous inhabitants, depending on permits that were typically less generous than those granted to gentile indigenous inhabitants (Einwohner, as opposed to Bürger, or citizen). In the 18th century, some Jews and their families (such as Daniel Itzig in Berlin) gained equal status with their Christian fellow city dwellers, but had a different status from noblemen, Huguenots, or serfs. They often did not enjoy the right to freedom of movement across territorial or even municipal boundaries, let alone the same status in any new place as in their previous location.

With the abolition of differences in legal status during the Napoleonic era and its aftermath, citizenship was established as a new franchise generally applying to all former subjects of the monarchs. Prussia conferred citizenship on the Prussian Jews in 1812, though this by no means resulted in full equality with other citizens. Jewish emancipation did not eliminate all forms of discrimination against Jews, who often remained barred from holding official state positions. The German federal edicts of 1815 merely held out the prospect of full equality, but it was not genuinely implemented at that time, and even the promises which had been made were modified. However, such forms of discrimination were no longer the guiding principle for ordering society, but a violation of it. In Austria, many laws restricting the trade and traffic of Jewish subjects remained in force until the middle of the 19th century in spite of the patent of toleration. Some of the crown lands, such as Styria and Upper Austria, forbade any Jews to settle within their territory; in Bohemia, Moravia, and Austrian Silesia many cities were closed to them. The Jews were also burdened with heavy taxes and imposts.

In the German Kingdom of Prussia, the government materially modified the promises made in the disastrous year of 1813. The promised uniform regulation of Jewish affairs was time and again postponed. In the period between 1815 and 1847, no less than 21 territorial laws affecting Jews in the older eight provinces of the Prussian state were in effect, each having to be observed by part of the Jewish community. At that time, no official was authorized to speak in the name of all Prussian Jews, or Jewry in most of the other 41 German states, let alone for all German Jews.

Nevertheless, a few men came forward to promote their cause, foremost among them being Gabriel Riesser (d. 1863), a Jewish lawyer from Hamburg, who demanded full civic equality for his people. He won over public opinion to such an extent that this equality was granted in Prussia on 6 April 1848, in Hanover and Nassau on 5 September and on 12 December, respectively, and also in his home state of Hamburg, then home to the second-largest Jewish community in Germany.[17][بحاجة لمصدر] In Württemberg, equality was conceded on 3 December 1861; in Baden on 4 October 1862; in Holstein on 14 July 1863; and in Saxony on 3 December 1868. After the establishment of the North German Confederation by the law of 3 July 1869, all remaining statutory restrictions imposed on the followers of different religions were abolished; this decree was extended to all the states of the German empire after the events of 1870.

التنوير اليهودي

During the General Enlightenment (the 1600s to late 1700s), many Jewish women began to frequently visit non-Jewish salons and to campaign for emancipation. In Western Europe and the German states, observance of Jewish law, Halacha, started to be neglected. In the 18th century, some traditional German scholars and leaders, such as the doctor and author of Ma'aseh Tuviyyah, Tobias b. Moses Cohn, appreciated the secular culture. The most important feature during this time was the German Aufklärung, which was able to boast of native figures who competed with the finest Western European writers, scholars, and intellectuals. Aside from the externalities of language and dress, the Jews internalized the cultural and intellectual norms of German society. The movement, becoming known as the German or Berlin Haskalah offered many effects to the challenges of German society. As early as the 1740s, many German Jews and some individual Polish and Lithuanian Jews had a desire for secular education. The German-Jewish Enlightenment of the late 18th century, the Haskalah, marks the political, social, and intellectual transition of European Jewry to modernity. Some of the elite members of Jewish society knew European languages. Absolutist governments in Germany, Austria, and Russia deprived the Jewish community's leadership of its authority and many Jews became 'Court Jews'. Using their connections with Jewish businessmen to serve as military contractors, managers of mints, founders of new industries and providers to the court of precious stones and clothing, they gave economic assistance to the local rulers. Court Jews were protected by the rulers and acted as did everyone else in society in their speech, manners, and awareness of European literature and ideas. Isaac Euchel, for example, represented a new generation of Jews. He maintained a leading role in the German Haskalah, is one of the founding editors of Ha-Me/assef. Euchel was exposed to European languages and culture while living in Prussian centers: Berlin and Koenigsberg. His interests turned towards promoting the educational interests of the Enlightenment with other Jews. Moses Mendelssohn as another enlightenment thinker was the first Jew to bring secular culture to those living an Orthodox Jewish life. He valued reason and felt that anyone could arrive logically at religious truths while arguing that what makes Judaism unique is its divine revelation of a code of law. Mendelssohn's commitment to Judaism leads to tensions even with some of those who subscribed to Enlightenment philosophy. Faithful Christians who were less opposed to his rationalistic ideas than to his adherence to Judaism found it difficult to accept this Juif de Berlin. In most of Western Europe, the Haskalah ended with large numbers of Jews assimilating. Many Jews stopped adhering to Jewish law, and the struggle for emancipation in Germany awakened some doubts about the future of Jews in Europe and eventually led to both immigrations to America and Zionism. In Russia, antisemitism ended the Haskalah. Some Jews responded to this antisemitism by campaigning for emancipation, while others joined revolutionary movements and assimilated, and some turned to Jewish nationalism in the form of the Zionist Hibbat Zion movement. [18]

إعادة تنظيم المجتمع اليهودي الألماني

Abraham Geiger and Samuel Holdheim were two founders of the conservative movement in modern Judaism who accepted the modern spirit of liberalism. Samson Raphael Hirsch defended traditional customs, denying the modern "spirit". Neither of these beliefs was followed by the faithful Jews. Zecharias Frankel created a moderate reform movement in assurance with German communities. Public worships were reorganized, reduction of medieval additions to the prayer, congregational singing was introduced, and regular sermons required scientifically trained rabbis. Religious schools were enforced by the state due to a want for the addition of religious structure to secular education of Jewish children. Pulpit oratory started to thrive mainly due to German preachers, such as M. Sachs and M. Joel. Synagogal music was accepted with the help of Louis Lewandowski. Part of the evolution of the Jewish community was the cultivation of Jewish literature and associations created with teachers, rabbis, and leaders of congregations.

Another vital part of the reorganization of the Jewish-German community was the heavy involvement of Jewish women in the community and their new tendencies to assimilate their families into a different lifestyle. Jewish women were contradicting their view points in the sense that they were modernizing, but they also tried to keep some traditions alive. German Jewish mothers were shifting the way they raised their children in ways such as moving their families out of Jewish neighborhoods, thus changing who Jewish children grew up around and conversed with, all in all shifting the dynamic of the then close-knit Jewish community. Additionally, Jewish mothers wished to integrate themselves and their families into German society in other ways.[19] Because of their mothers, Jewish children participated in walks around the neighborhood, sporting events, and other activities that would mold them into becoming more like their other German peers. For mothers to assimilate into German culture, they took pleasure in reading newspapers and magazines that focused on the fashion styles, as well as other trends that were up and coming for the time and that the Protestant, bourgeois Germans were exhibiting. Similar to this, German-Jewish mothers also urged their children to partake in music lessons, mainly because it was a popular activity among other Germans. Another effort German-Jewish mothers put into assimilating their families was enforcing the importance of manners on their children. It was noted that non-Jewish Germans saw Jews as disrespectful and unable to grasp the concept of time and place.[19] Because of this, Jewish mothers tried to raise their kids having even better manners than the Protestant children in an effort to combat the pre-existing stereotype put on their children. In addition, Jewish mothers put a large emphasis on proper education for their children in hopes that this would help them grow up to be more respected by their communities and eventually lead to prosperous careers. While Jewish mothers worked tirelessly on ensuring the assimilation of their families, they also attempted to keep the familial aspect of Jewish traditions. They began to look at Shabbat and holidays as less of culturally Jewish days, but more as family reunions of sorts. What was once viewed as a more religious event became more of a social gathering of relatives.[19]

مولد الحركة الإصلاحية

The beginning of the Reform Movement in Judaism was emphasized by David Philipson, who was the rabbi at the largest Reform congregation. The increasing political centralization of the late 18th and early 19th centuries undermined the societal structure that perpetuated traditional Jewish life. Enlightenment ideas began to influence many intellectuals, and the resulting political, economic, and social changes were overpowering. Many Jews felt a tension between Jewish tradition and the way they were now leading their lives – religiously – resulting in less tradition. As the insular religious society that reinforced such observance disintegrated, falling away from vigilant observance without deliberately breaking with Judaism was easy. Some tried to reconcile their religious heritage with their new social surroundings; they reformed traditional Judaism to meet their new needs and to express their spiritual desires. A movement was formed with a set of religious beliefs, and practices that were considered expected and tradition. Reform Judaism was the first modern response to the Jew's emancipation, though reform Judaism differing in all countries caused stresses of autonomy on both the congregation and individual. Some of the reforms were in the practices: circumcisions were abandoned, rabbis wore vests after Protestant ministers, and instrumental accompaniment was used: pipe organs. In addition, the traditional Hebrew prayer book was replaced by German text, and reform synagogues began being called temples which were previously considered the Temple of Jerusalem. Reform communities composed of similar beliefs and Judaism changed at the same pace as the rest of society had. The Jewish people have adapted to religious beliefs and practices to the meet the needs of the Jewish people throughout the generation.[20]

ألمانيا منذ عصر النهضة

بحلول القرن السادس عشر، كانت السلطة المركزية في ألمانيا قد اختفت تقريباً، فتم عزل أعضاء الجماعات اليهودية داخل الجيتوات، وفرضـت عليهـم قوانين مهينـة وطُردوا من كثير من المدن والإمارات الألمانية. ولكن، مع هذا، لم يتم طردهم تماماً من كل ألمانيا. فكان بوسعهم الانتقال إلى إحدى الإمارات التي تحتاج إلى خدمتهم.

وشهدت هذه الفترة بدايات ظهور الرأسمالية التجارية التي سبَّبت شقاء للجماهير لم يدركوا مصدره. وكان اليهودي هو الرمز الواضح مرة أخرى لهذا الشقاء. كما أن الطبقات التجارية الصاعدة من سكان المدن دخلت في صراع مع الأمراء ورجال الكنيسة. وكان اليهودي هو حلبة الصراع، فحاول كل طرف الاستفادة من اليهود باعتبارهم عنصراً تجارياً. وكانت العناصر التجارية المحلية ترى في اليهودي غريماً لها، وخصوصـاً أنـه كان أداة في يـد النبلاء. وظهر مارتن لوثر في تلك المرحلة، فطرح رؤيته الخاصة بضرورة تنصير اليهود. ومع نهاية القرن السادس عشر، لم يبق سوى بضع جماعات يهودية في فرانكفورت وورمز وفيينا وبراغ.

وتركت حرب الثلاثين عاماً (1618-1648) أثرها العميق في يهود ألمانيا، فبعد انتهائها، أصبحت ألمانيا مجموعة غير متماسكة من الدويلات المستقلة تحت حكم حكام مطلقين في حاجة إلى السكان والمال، وهي دويلات (إمارات ودوقيات) ذات تَوجُّه مركنتالي ترى أن مصلحة الدولة هي المصلحة العليا التي تَجب القيم والمثل الأخرى كافة. وكان أعضاء الجماعة اليهودية عنصراً أساسياً في عملية إعادة البناء والبعث التجاري ومصدراً أساسياً للضرائب، كما أصبحوا جزءاً لا يتجزأ من النظام الاقتصادي الجديد.

وشهد القرن السابع عشر كذلك استقرار يهود المارانو في هامبورج حيث أسسوا بنك هامبورج، وبدأت هجرة يهود شرق أوربا من بولندا، بعد هجمات شميلنكي، حيث استوطنت أعداد منهم في هامبورج وغيرها من المدن.

وظهرت تجمعات يهودية في داساو ومانهايم وليبزيج ودرسدن. وفي داخل هذا الإطار، ظهر يهود البلاط الذين ساعدوا الدويلات والإمارات التي كانوا يتبعونها على تنظيم أمورها المالية واستثماراتها، ورتبوا لها الاعتمادات اللازمة لمشاريعها وحروبها ولتمويل مظاهر الترف التي كانت تُشكِّل عنصراً أساسياً بالنسبة للحكام المطلقين. وكان يهود البلاط في منزلة وزير الخارجية والمالية ورئيس المخابرات. فكانوا يقومون بجمع المعلومات، كما كانوا أداة مهمة في يد الحكام المطلقين الألمان لابتزاز جماهيرهم وزيادة ريع الدولة. وكان يهودي البلاط (وهو عادةً قائد الجماعة اليهودية) يُعَدُّ عنصراً موالياً للدولة مكروهاً من جماهيرها، وهو ما جعل وضع الجماعة ككل محفوفاً بالمخاطر.

الحرية والقمع (1815–ع. 1830)

وتأثر وضع يهود ألمانيا بالثورة الفرنسية التي عَجَّلت بعملية إعتاقهم. وبعد سقوط نابليون، تقهقر وضعهم قليلاً. ولكنهم مُنحوا حقوقهم إبّان القرن التاسع عشر، وزاد اندماجهم بدرجة كبيرة. وظهرت بعد ذلك حركة التنوير، واليهودية الإصلاحية، والاتجاهات اليهودية الأخرى. ومع منتصف القرن، كان اليهود قد حصلوا على معظم حقوقهم. وفي الفترة من 1871 إلى 1914، كانوا قد حصلوا على حقوقهم كاملة واندمجوا في المحيط الثقافي تماماً، فتنصرت نسبة عالية من مثقفيهم، مثل هايني ووالد كارل ماركس وأولاد مندلسون وغيرهم، واختفت أعداد كبيرة منهم عن طريق الزواج المختلط.

1815–1918

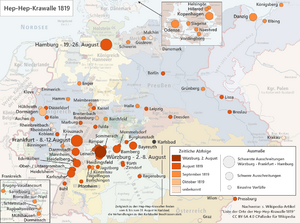

Napoleon I emancipated the Jews across Europe, but with Napoleon's fall in 1815, growing nationalism resulted in increasing repression. From August to October 1819, pogroms that came to be known as the Hep-Hep riots took place throughout Germany. Jewish property was destroyed in large number.

During this time, many German states stripped Jews of their civil rights. In the Free City of Frankfurt, only 12 Jewish couples were allowed to marry each year, and the 400,000 florins the city's Jewish community had paid in 1811 for its emancipation were forfeited. After the Rhineland reverted to Prussian control, Jews lost the rights Napoleon had granted them, were banned from certain professions, and the few who had been appointed to public office before the Napoleonic Wars were dismissed.[[#cite_note-FOOTNOTEElon2002[[تصنيف:مقالات_بالمعرفة_بحاجة_لذكر_رقم_الصفحة_بالمصدر_from_December_2021]][[Category:Articles_with_invalid_date_parameter_in_template]]<sup_class="noprint_Inline-Template_"_style="white-space:nowrap;">[<i>[[المعرفة:Citing_sources|<span_title="هذه_المقولة_تحتاج_مرجع_إلى_صفحة_محددة_أو_نطاق_من_الصفحات_تظهر_فيه_المقولة'"`UNIQ--nowiki-00000025-QINU`"'_(December_2021)">صفحة مطلوبة</span>]]</i>]</sup>-21|[21]]] Throughout numerous German states, Jews had their rights to work, settle, and marry restricted. Without special letters of protection, Jews were banned from many different professions, and often had to resort to jobs considered unrespectable, such as peddling or cattle dealing, to survive. A Jewish man who wanted to marry had to purchase a registration certificate, known as a Matrikel, proving he was in a "respectable" trade or profession. A Matrikel, which could cost up to 1,000 florins, was usually restricted to firstborn sons.[22] As a result, most Jewish men were unable to legally marry. Throughout Germany, Jews were heavily taxed, and were sometimes discriminated against by gentile craftsmen.

As a result, many German Jews began to emigrate. The emigration was encouraged by German-Jewish newspapers.[22] At first, most emigrants were young, single men from small towns and villages. A smaller number of single women also emigrated. Individual family members would emigrate alone, and then send for family members once they had earned enough money. Emigration eventually swelled, with some German Jewish communities losing up to 70% of their members. At one point, a German-Jewish newspaper reported that all the young Jewish males in the Franconian towns of Hagenbach, Ottingen, and Warnbach had emigrated or were about to emigrate.[22] The United States was the primary destination for emigrating German Jews.

The Revolutions of 1848 swung the pendulum back towards freedom for the Jews. A noted reform rabbi of that time was Leopold Zunz, a contemporary and friend of Heinrich Heine. In 1871, with the unification of Germany by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, came their emancipation, but the growing mood of despair among assimilated Jews was reinforced by the antisemitic penetrations of politics. In the 1870s, antisemitism was fueled by the financial crisis and scandals; in the 1880s by the arrival of masses of Ostjuden, fleeing from Russian territories; by the 1890s it was a parliamentary presence, threatening anti-Jewish laws. In 1879 the Hamburg pamphleteer Wilhelm Marr introduced the term 'antisemitism' into the political vocabulary by founding the Antisemitic League.[23] Antisemites of the völkisch movement were the first to describe themselves as such, because they viewed Jews as part of a Semitic race that could never be properly assimilated into German society. Such was the ferocity of the anti-Jewish feeling of the völkisch movement that by 1900, antisemitic had entered German to describe anyone who had anti-Jewish feelings. However, despite massive protests and petitions, the völkisch movement failed to persuade the government to revoke Jewish emancipation, and in the 1912 Reichstag elections, the parties with völkisch-movement sympathies suffered a temporary defeat.

Jews experienced a period of legal equality after 1848. Baden and Württemberg passed the legislation that gave the Jews complete equality before the law in 1861–64. The newly formed German Empire did the same in 1871.[24] Historian Fritz Stern concludes that by 1900, what had emerged was a Jewish-German symbiosis, where German Jews had merged elements of German and Jewish culture into a unique new one. Marriages between Jews and non-Jews became somewhat common from the 19th century; for example, the wife of German Chancellor Gustav Stresemann was Jewish. However, opportunity for high appointments in the military, the diplomatic service, judiciary or senior bureaucracy was very small.[25] Some historians believe that with emancipation the Jewish people lost their roots in their culture and began only using German culture. However, other historians including Marion A. Kaplan, argue that it was the opposite and Jewish women were the initiators of balancing both Jewish and German culture during Imperial Germany.[26] Jewish women played a key role in keeping the Jewish communities in tune with the changing society that was evoked by the Jews being emancipated. Jewish women were the catalyst of modernization within the Jewish community. The years 1870–1918 marked the shift in the women's role in society. Their job in the past had been housekeeping and raising children. Now, however, they began to contribute to the home financially. Jewish mothers were the only tool families had to linking Judaism with German culture. They felt it was their job to raise children that would fit in with bourgeois Germany. Women had to balance enforcing German traditions while also preserving Jewish traditions. Women were in charge of keeping kosher and the Sabbath; as well as, teaching their children German speech and dressing them in German clothing. Jewish women attempted to create an exterior presence of German while maintaining the Jewish lifestyle inside their homes.[26]

During the history of the German Empire, there were various divisions within the German Jewish community over its future; in religious terms, Orthodox Jews sought to keep to Jewish religious tradition, while liberal Jews sought to "modernise" their communities by shifting from liturgical traditions to organ music and German-language prayers.

Many immigrants travelled through Germany on the way to other countries. By the outbreak of World War I, five million emigrants from Russia had passed through German territory. Around two million Jews passed through the eastern border of Germany between 1880 and 1914 with around 78,000 remaining in Germany.[27]

The Jewish population grew from 512,000 in 1871 to 615,000 in 1910, including 79,000 recent immigrants from Russia, just under one percent of the total. About 15,000 Jews converted to Christianity between 1871 and 1909.[28] The typical attitude of German liberals towards Jews was that they were in Germany to stay and were capable of being assimilated; anthropologist and politician Rudolf Virchow summarised this position, saying "The Jews are simply here. You cannot strike them dead." This position, however, did not tolerate cultural differences between Jews and non-Jews, advocating instead eliminating this difference.[29]

الحرب العالمية الأولى

A higher percentage of German Jews fought in World War I than of any other ethnic, religious or political minority in Germany; around 12,000 died in the fighting.[30][31]

Many German Jews supported the war out of patriotism; like many Germans, they viewed Germany's actions as defensive in nature and even left-liberal Jews believed Germany was responding to the actions of other countries, particularly Russia. For many Jews it was never a question as to whether or not they would stand behind Germany, it was simply a given that they would. The fact that the enemy was Russia also gave an additional reason for German Jews to support the war; Tsarist Russia was regarded as the oppressor in the eyes of German Jews for its pogroms and for many German Jews, the war against Russia would become a sort of holy war. While there was partially a desire for vengeance, for many Jews ensuring Russia's Jewish population was saved from a life of servitude was equally important – one German-Jewish publication stated "We are fighting to protect our holy fatherland, to rescue European culture and to liberate our brothers in the east."[32][33] War fervour was as common amongst Jewish communities as it was amongst ethnic Germans ones. The main Jewish organisation in Germany, the Central Association of German Citizens of the Jewish Faith, declared unconditional support for the war and when 5 August was declared by the Kaiser to be a day of patriotic prayer, synagogues across Germany surged with visitors and filled with patriotic prayers and nationalistic speeches.[34]

While going to war brought the unsavoury prospect of fighting fellow Jews in Russia, France and Britain, for the majority of Jews this severing of ties with Jewish communities in the Entente was accepted part of their spiritual mobilisation for war. After all, the conflict also pitted German Catholics and Protestants against their fellow believers in the east and west. Indeed, for some Jews the fact that Jews were going to war with one another was proof of the normality of German-Jewish life; they could no longer be considered a minority with transnational loyalties but loyal German citizens. German Jews often broke ties with Jews of other countries; the Alliance Israélite Universelle, a French organisation that was dedicated to protecting Jewish rights, saw a German Jewish member quit once the war started, declaring that he could not, as a German, belong to a society that was under French leadership.[36] German Jews supported German colonial ambitions in Africa and Eastern Europe, out of the desire to increase German power and to rescue Eastern European Jews from Tsarist rule. The eastern advance became important for German Jews because it combined German military superiority with rescuing Eastern Jews from Russian brutality; Russian antisemitism and pogroms had only worsened as the war dragged on.[37][38] However, German Jews did not always feel a personal kinship with Russian Jews. Many were repelled by Eastern Jews, who dressed and behaved differently, as well as being much more religiously devout. Victor Klemperer, a German Jew working for military censors, stated "No, I did not belong to these people, even if one proved my blood relation to them a hundred times over...I belonged to Europe, to Germany, and I thanked my creator that I was German."[39] This was a common attitude amongst ethnic Germans however; during the invasion of Russia the territories the Germans overran seemed backwards and primitive, thus for many Germans their experiences in Russia simply reinforced their national self-concept.[40]

Prominent Jewish industrialists and bankers, such as Walter Rathenau and Max Warburg played major roles in supervising the German war economy.

In October 1916, the German Military High Command administered the Judenzählung (census of Jews). Designed to confirm accusations of the lack of patriotism among German Jews, the census disproved the charges, but its results were not made public.[41] Denounced as a "statistical monstrosity",[42] the census was a catalyst to intensified antisemitism and social myths such as the "stab-in-the-back myth" (Dolchstoßlegende).[43] For many Jews, the fact the census was carried out at all caused a sense of betrayal, as German Jews had taken part in the violence, food shortages, nationalist sentiment and misery of attrition alongside their fellow Germans, however most German-Jewish soldiers carried on dutifully to the bitter end.[37]

When strikes broke out in Germany towards the end of the war, some Jews supported them. However, the majority of Jews had little sympathy for the strikers and one Jewish newspaper accused the strikers of "stabbing the frontline army in the back." Like many Germans, German Jews would lament the Treaty of Versailles.[37]

سنوات ڤايمار، 1919–33

Under the Weimar Republic, 1919–1933, German Jews played a major role in politics and diplomacy for the first time in their history, and they strengthened their position in financial, economic, and cultural affairs.[44][45] Hugo Preuß was Interior Minister under the first post-imperial regime and wrote the first draft of the liberal Weimar Constitution.[46] Walther Rathenau, chairman of the General Electricity Company (AEG), served as foreign minister in 1922, when he negotiated the important Treaty of Rapallo. He was assassinated two months later.[47]

In 1914, Jews were well-represented among the wealthy, including 23.7 percent of the 800 richest individuals in Prussia, and eight percent of the university students.[48] Jewish businesses, however, no longer had the economic prominence they had in previous decades.[49] The Jewish middle class suffered increasing economic deprivation, and by 1930 a quarter of the German Jewish community had to be supported through community welfare programs.[49] Germany's Jewish community was also highly urbanized, with 80 percent living in cities.[50]

معاداة السامية

There was sporadic antisemitism based on the false allegation that wartime Germany had been betrayed by an enemy within. There was some violence against German Jews in the early years of the Weimar Republic, and it was led by the paramilitary Freikorps. The Protocols of the Elders of Zion (1920), a forgery which claimed that Jews were taking over the world, was widely circulated. The second half of the 1920s were prosperous, and antisemitism was much less noticeable. When the Great Depression hit in 1929, it surged again as Adolf Hitler and his Nazi party promoted a virulent strain.

Author Jay Howard Geller says that four possible responses were available to the German Jewish community. The majority of German Jews were only nominally religious and they saw their Jewish identity as only one of several identities; they opted for bourgeois liberalism and assimilation into all phases of German culture. A second group (especially recent migrants from eastern Europe) embraced Judaism and Zionism. A third group of left-wing elements endorsed the universalism of Marxism, which downplayed ethnicity and antisemitism. A fourth group contained some who embraced hardcore German nationalism and minimized or hid their Jewish heritage. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, a fifth option was seized upon by hundreds of thousands: escape into exile, typically at the cost of leaving all wealth behind.[51]

The German legal system generally treated Jews fairly throughout the period.[52] The Centralverein, the major organization of German Jewry, used the court system to vigorously defend Jewry against antisemitic attacks across Germany; it proved generally successful.[53]

المثقفون

Jewish intellectuals and creative professionals were among the leading figures in many areas of Weimar culture. German university faculties became universally open to Jewish scholars in 1918. Leading Jewish intellectuals on university faculties included physicist Albert Einstein; sociologists Karl Mannheim, Erich Fromm, Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Herbert Marcuse; philosophers Ernst Cassirer and Edmund Husserl; communist political theorist Arthur Rosenberg; sexologist and pioneering LGBT advocate Magnus Hirschfeld, and many others. Seventeen German citizens were awarded Nobel prizes during the Weimar Republic (1919–1933), five of whom were Jewish scientists. The German-Jewish literary magazine, Der Morgen, was established in 1925. It published essays and stories by prominent Jewish writers such as Franz Kafka and Leo Hirsch until its liquidation by the Nazi government in 1938.[54][55]

وكان إتمام دمج يهود ألمانيا وتحديثهم على نمط يهود الغرب ممكناً. فيهود ألمانيا كانوا يعتبرون أنفسهم من يهود الغرب باعتبار أن يهود شرق أوربا هم يهود الشرق، كما أن ارتباط يهود أوربا بالثقافة الألمانية كان أمراً واضحاً. ولكن ثمة ظروفاً خاصة بهم وببنية المجتمع الألماني أدَّت في نهاية الأمر إلى تصفيتهم وتصفية يهود أوربا خارج الاتحاد السوفيتي، وهي الظروف التي أدَّت إلى الإبادة.

اليهود تحت الحكم النازي (1933–1939)

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| الهولوكوست |

|---|

|

In Germany, according to historian Hans Mommsen, there were three types of antisemitism. In a 1997 interview, Mommsen was quoted as saying:

One should differentiate between the cultural antisemitism symptomatic of the German conservatives—found especially in the German officer corps and the high civil administration—and mainly directed against the Eastern Jews on the one hand, and völkisch antisemitism on the other. The conservative variety functions, as Shulamit Volkov has pointed out, as something of a "cultural code." This variety of German antisemitism later on played a significant role insofar as it prevented the functional elite from distancing itself from the repercussions of racial antisemitism. Thus, there was almost no relevant protest against the Jewish persecution on the part of the generals or the leading groups within the Reich government. This is especially true with respect to Hitler's proclamation of the "racial annihilation war" against the Soviet Union. Besides conservative antisemitism, there existed in Germany a rather silent anti-Judaism within the Catholic Church, which had a certain impact on immunizing the Catholic population against the escalating persecution. The famous protest of the Catholic Church against the euthanasia program was, therefore, not accompanied by any protest against the Holocaust.

The third and most vitriolic variety of antisemitism in Germany (and elsewhere) is the so-called völkisch antisemitism or racism, and this is the foremost advocate of using violence.[56]

In 1933, persecution of the Jews became an active Nazi policy, but at first laws were not as rigorously obeyed or as devastating as in later years. Such clauses, known as Aryan paragraphs, had been postulated previously by antisemitism and enacted in many private organizations.

The continuing and exacerbating abuse of Jews in Germany triggered calls throughout March 1933 by Jewish leaders around the world for a boycott of German products. The Nazis responded with further bans and boycotts against Jewish doctors, shops, lawyers and stores. Only six days later, the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service was passed, banning Jews from being employed in government. This law meant that Jews were now indirectly and directly dissuaded or banned from privileged and upper-level positions reserved for "Aryan" Germans. From then on, Jews were forced to work at more menial positions, beneath non-Jews, pushing them to more labored positions.

The Civil Service Law reached immediately into the education system because university professors, for example, were civil servants. While the majority of the German intellectual classes were not thoroughgoing National Socialists,[57] academia had been suffused with a "cultured antisemitism" since imperial times, even more so during Weimar.[58] With the majority of non-Jewish professors holding such feelings about Jews, coupled with how the Nazis' outwardly appeared in the period during and after the seizure of power, there was little motivation to oppose the anti-Jewish measures being enacted—few did, and many were actively in favor.[59] According to a German professor of the history of mathematics, "There is no doubt that most of the German mathematicians who were members of the professional organization collaborated with the Nazis, and did nothing to save or help their Jewish colleagues."[60] "German physicians were highly Nazified, compared to other professionals, in terms of party membership," observed Raul Hilberg[61] and some even carried out experiments on human beings at places like Auschwitz.[62]

On 2 August 1934, President Paul von Hindenburg died. No new president was appointed. Instead, the functions and ceremony of the presidency were merged with that of the chancellor, making Hitler, as Führer, both head of state and head of government. This power consolidation, and a lame-duck Reichstag with no true opposition parties, gave Adolf Hitler totalitarian control of law-making. The army also swore an oath of loyalty personally to Hitler, giving him absolute power over the military; this position allowed him to enforce his anti-Semitic beliefs further by creating more state pressure on the Jews than ever before.

In 1935 and 1936, the pace of persecution of the Jews increased. In May 1935, Jews were forbidden to join the Wehrmacht (Armed Forces), and that year, anti-Jewish propaganda appeared in Nazi German shops and restaurants. The Nuremberg Racial Purity Laws were passed around the time of the Nazi rallies at Nuremberg; on 15 September 1935, the Law for the Protection of German Blood and Honor was passed, preventing sexual relations and marriages between Aryans and Jews. At the same time the Reich Citizenship Law was passed and was reinforced in November by a decree, stating that all Jews, even quarter- and half-Jews, were no longer citizens (Reichsbürger) of their own country. Their official status became Reichsangehöriger, "subject of the state". This meant that they had no basic civil rights, such as the right to vote, though elections in Germany by this time were total shams, where voters could only vote for Nazi candidates and "approve" decrees set by the regime. This removal of basic citizens' rights anticipated even harsher laws and proscriptions against Jews. The drafting of the Nuremberg Laws is often attributed to Hans Globke.[بحاجة لمصدر]

In 1936, Jews were banned from all professional jobs, effectively preventing them from exerting any influence in education, politics, higher education, and business. Because of this, there was nothing to stop the anti-Jewish actions that spread across the Nazi-German economy.[بحاجة لمصدر]

After the Night of the Long Knives, the Schutzstaffel (SS) became the dominant policing power in Germany. Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler was a virulent anti-Semite and zealous executor of regime anti-Semitic policy who gained a near-total monopoly on law enforcement and state security functions in Nazi Germany by 1936. Since the SS had started as Hitler's personal bodyguard, its members were far more loyal and disciplined than those of the Sturmabteilung (SA) had been. Because of this, they were also supported, though distrusted, by the Wehrmacht, which was now more willing to submit to Hitler's decrees than when the SA was dominant.[بحاجة لمصدر] All of this allowed Hitler more direct control over government and political attitude towards Jews in Nazi Germany. In 1937 and 1938, new laws were implemented, and the segregation of Jews from the true "Aryan" German population was started. In particular, Jews were penalized financially for their perceived racial status.

On 4 June 1937, two young German Jews, Helmut Hirsch and Isaac Utting, were both executed for being involved in a plot to bomb the Nazi party headquarters in Nuremberg.[بحاجة لمصدر]

As of 1 March 1938, government contracts could no longer be awarded to Jewish businesses. On 30 September, "Aryan" doctors could only treat "Aryan" patients. Provision of medical care to Jews was already hampered by the fact that Jews were banned from being doctors or having any professional jobs.[بحاجة لمصدر]

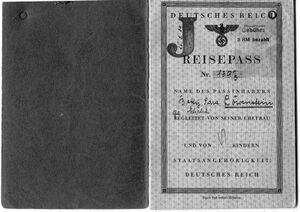

Beginning 17 August 1938, Jews with first names of non-Jewish origin had to add Israel (males) or Sarah (females) to their names, and a large J was to be imprinted on their passports beginning 5 October.[63] On 15 November Jewish children were banned from going to normal schools. By April 1939, nearly all Jewish companies had either collapsed under financial pressure and declining profits, or had been forced to sell out to the Nazi German government. This further reduced Jews' rights as human beings. They were in many ways officially separated from the German population.

The increasingly totalitarian, militaristic regime which was being imposed on Germany by Hitler allowed him to control the actions of the SS and the military. On 7 November 1938, a young Polish Jew, Herschel Grynszpan, attacked and shot two German officials in the Nazi German embassy in Paris. (Grynszpan was angry about the treatment of his parents by the Nazis.) On 9 November the German Attache, Ernst vom Rath, who had been shot by Grynszpan, died. Joseph Goebbels issued instructions that demonstrations against Jews were to be organized and undertaken in retaliation throughout Germany. On 10 November 1938, Reinhard Heydrich ordered the state police and the Sturmabteilung (SA) to destroy Jewish property and arrest as many Jews as possible in what became known as the Night of Broken Glass (Kristallnacht).[64] The storefronts of Jewish shops and offices were smashed and vandalized, and many synagogues were destroyed by fire. Approximately 91 Jews were killed, and another 30,000 arrested, mostly able bodied males, all of whom were sent to the newly formed concentration camps. In the following 3 months some 2,000–2,500 of them died in the concentration camps, the rest were released under the condition that they leave Germany. Many Germans were disgusted by this action when the full extent of the damage was discovered, so Hitler ordered that it be blamed on the Jews. The Nazis announced the "Jewish Capital Levy" (ألمانية: Judenvermögensabgabe), a one billion Reichsmark tax (equivalent to US$3.9 billion in 2022). Any Jews owning assets exceeding قالب:Reichsmark had to surrender 20% of those assets.[65] The Jews also had to repair all damages at their own cost.

Increasing antisemitism prompted a wave of Jewish mass emigration from Germany throughout the 1930s. Among the first wave were intellectuals, politically active individuals, and Zionists. However, as Nazi legislation worsened the Jews' situation, more Jews wished to leave Germany, with a panicked rush in the months after Kristallnacht in 1938.

Mandatory Palestine was a popular destination for German Jewish emigration. Soon after the Nazis' rise to power in 1933, they negotiated the Haavara Agreement with Zionist authorities in Palestine, which was signed on 25 August 1933. Under its terms, 60,000 German Jews were to be allowed to emigrate to Palestine.[66] During the Fifth Aliyah, between 1929 and 1939, a total of 250,000 Jewish immigrants arrived in Palestine—more than 55,000 of them from Germany, Austria, or Bohemia. Many of them were doctors, lawyers, engineers, architects, and other professionals, who contributed greatly to the development of the Yishuv.

The United States was another destination for German Jews seeking to leave the country, though the number allowed to immigrate was restricted due to the Immigration Act of 1924. Between 1933 and 1939, more than 300,000 Germans, of whom about 90% were Jews, applied for immigration visas to the United States. By 1940, only 90,000 German Jews had been granted visas and allowed to settle in the United States. Some 100,000 German Jews also moved to Western European countries, especially France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. However, these countries would later be occupied by Germany, and most of them would still fall victim to the Holocaust. Another 48,000 emigrated to the United Kingdom and other European countries.[67][68]

الهولوكوست في ألمانيا

Overall, of the 522,000 Jews living in Germany in January 1933, approximately 304,000 emigrated during the first six years of Nazi rule and about 214,000 were left on the eve of World War II. Of these, 160,000–180,000 were killed as a part of the Holocaust. Those that remained in Germany went into hiding and did everything they could to survive. Commonly referred to as "dashers and divers," the Jews lived a submerged life and experienced the struggle to find food, a relatively secure hiding space or shelter, and false identity papers while constantly evading Nazi police and strategically avoiding checkpoints. Non-Jews offered support by allowing the Jews to hide in their homes but when this proved to be too dangerous for both parties, the Jews were forced to seek shelter in more exposed locations including the street. Some Jews were able to attain false papers, despite the risks and sacrifice of resources doing so required. A reliable false ID would cost between 2,000RM and 6,000RM depending on where it came from. Some Jews in Berlin looked to the Black Market to get false papers as this was a most sought-after product following food, tobacco, and clothing. Certain forms of ID were soon deemed unacceptable, leaving the Jews with depleted resources and vulnerable to being arrested. Avoiding arrest was particularly challenging in 1943 as the Nazi police increased their personnel and inspection checkpoints, leading to 65 percent of all submerged Jews being detained and likely deported.[69] On 19 May 1943, only about 20,000 Jews remained and Germany was declared judenrein (clean of Jews; also judenfrei: free of Jews).[70]

بقاء معاداة السامية

During the medieval period antisemitism flourished in Germany. Especially during the time of the Black Death from 1348 to 1350 hatred and violence against Jews increased. Approximately 72% of towns with a Jewish settlement suffered from violent attacks against the Jewish population.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Regions that suffered from the Black Death pogroms were 6 times more likely to engage in antisemitic violence during the 1920s, racist and fascist parties like the DNVP, NSDAP and DVFP gained a 1.5 times higher voting share in the 1928 election, their inhabitants wrote more letters to antisemitic newspapers like "Der Stürmer", and they deported more Jews during the Nazi reign. This is due to cultural transmission.[71]

According to a study by Nico Voigtländer and Hans-Joachim Voth, Germans who grew up during Nazi rule are significantly more antisemitic than Germans born before or after them. In addition, Voigtländer and Voth found Nazi antisemitic indoctrination was more effective in areas with pre-existing widespread antisemitism.[72]

A simple model of cultural transmission and persistence of attitudes comes from Bisin and Verdier, who state that children acquire their preference scheme through imitating their parents, who in turn attempt to socialize their children to their own preferences, without taking into consideration if these traits are useful or not.[73]

Economic factors had the potential to undermine this persistence throughout the centuries. Hatred against outsiders was more costly in trade open cities, like the members of the Hanseatic League. Faster growing cities saw less persistence in antisemitic attitudes, this may be due to the fact that trade-openness was associated with more economic success and therefore higher migration rates into these regions.[71]

من 1945 إلى إعادة التوحيد

وفي عام 1948، كان عدد أعضاء الجماعة اليهودية في ألمانيا عشرين ألفاً فقط، بلغ عام 1992 نحو 50.000 من مجموع عدد السكان البالغ 80.606.000. ويبدو أن الزيادة ناجمة عن هجرة أعداد كبيرة من اليهود مرة أخرى إلى ألمانيا، من بينهم أعداد كبيرة من الإسـرائيليين الذين تركَّزوا في مهن مشـينة مثـل الاتجار بالمخدرات والبغـاء.

ونشير هنا إلى بعض التنظيمات والمؤسسات الخاصة بأعضاء الجماعة اليهودية في ألمانيا:

أ) المجلس المركزي لليهود في ألمانيا. وهي المنظمة المركزية للجماعة اليهودية في ألمانيا والجهة التي تمثلهم لدى المؤتمر اليهودي العالمي ومقرها دوسلدورف. وتقوم برعاية المصالح السياسية للجماعة ورعاية المسائل الخاصة بالتعويضات، كما تهتم بمراقبة أي علامات قد تشير إلى احتمال بعث النازية.

ب) النداء اليهودي الموحَّد. وهي المنظمة الأساسية المسئولة عن جمع التبرعات وتدبير الموارد المالية ومقرها فرانكفورت.

جـ) المجلس المركزي لخدمات الرفاه الاجتماعي ليهود ألمانيا، ومقرها فرانكفورت. وهي المنظمة الأساسية العاملة في المجالات الخيرية ومجال الخدمة الاجتماعية.

د) مؤتمر حاخامات ألمانيا الغربية. وهو الإطار الذي يضم الحاخامات الذين يقومون بمهامهم الدينية بين أعضاء الجماعة اليهودية في تجمعاتهم المختلفة.

انظر أيضاً

- تاريخ اليهود في ألمانيا الشرقية

- قائمة اليهود الألمان

- Yekke

- يهود أشكناز

- الهولوكوست

- العلاقات الألمانية الإسرائيلية

- هگليل أونلاين – مجلة أونلاين لليهود في البلاد المتحدثة بالألمانية.

- Peter Stevens (RAF officer)

- تاريخ اليهود في كولونيا

- تاريخ اليهود في ساپير

المصادر

This article incorporates text from the 1901–1906 Jewish Encyclopedia, a publication now in the public domain.

هوامش

- ^ DellaPergola, Sergio (2019). "World Jewish Population, 2018" (PDF). American Jewish Year Book 2018. American Jewish Year Book. Vol. 118. p. 54. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-03907-3_8. ISBN 978-3-030-03906-6. S2CID 146549764.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةUSHMM1939-1945 - ^ Schoelkopf, Katrin. “Rabbiner Ehrenberg: Orthodoxes jüdisches Leben ist wieder lebendig in Berlin” (Rabbi Ehrenberg: Orthodox Jewish life is alive again in Berlin). Die Welt. November 18, 2004

- ^ Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Rome". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- ^ Davies, William D.; Frankenstein, Louis (1984). The Cambridge History of Judaism. Cambridge University Press. p. 1042. ISBN 1-397-80521-8.

- ^ Lieu, Judith; North, John; Rajak, Tessa (2013). The Jews Among Pagans and Christians in the Roman Empire. Routledge. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-135-08188-1.

- ^ "Already during Roman times, Jews resided in Cologne". Archäologische Zone – Jüdisches Museum. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ Adrian, Johanna. "A Jewish beginnings". Frankfurt/Oder: Institut für angewandte Geschichte. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- ^ "Cologne, City of the Arts '07". Archived from the original on 19 January 2009.

- ^ "Medieval Source book Legislation Affecting the Jews from 300 to 800 CE". Archived from the original on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- ^ "Cologne: Germany's Oldest Jewish Community". dw.com.

- ^ Gottheil, Richard; Broyde, Isaac. "CHARLEMAGNE - JewishEncyclopedia.com". www.jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 22 June 2025.

- ^ Ben-Sasson 2007, pp. 518–519.

- ^ Ben-Sasson, Haim Hillel (1976). "The Middle Ages," in: Ben-Sasson (Ed.), A History of the Jewish People (pp. 385–723). Translated from the Hebrew. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. p. 433.

- ^ "Germany / Up to the Crusades". The Jewish Encyclopedia. 1901–1906. p. 631.

- ^ Bach, Hans (Summer 1976). Moses Mendelssohn (2 ed.). p. 24. ProQuest 1312125181.

- ^ By the introduction of the basic freedoms decided on by the National Assembly, adopted into Hamburg's statutory law on 21 February 1849.

- ^ Barnouw, Dagmar (Summer 2002). "Origin and Transformation: Salomon Maimon and German-Jewish Enlightenment Culture". Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies. 20 (4): 64–80. doi:10.1353/sho.2002.0051. S2CID 144021515.

- ^ أ ب ت Kaplan, Marion. Gender and Jewish History in Imperial Germany. New York: Cambridge University Press.[صفحة مطلوبة]

- ^ Philipson, David (1903). "The Beginnings of the Reform Movement in Judaism". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 15 (3): 475–521. doi:10.2307/1450629. JSTOR 1450629.

- [[#cite_ref-FOOTNOTEElon2002[[تصنيف:مقالات_بالمعرفة_بحاجة_لذكر_رقم_الصفحة_بالمصدر_from_December_2021]][[Category:Articles_with_invalid_date_parameter_in_template]]<sup_class="noprint_Inline-Template_"_style="white-space:nowrap;">[<i>[[المعرفة:Citing_sources|<span_title="هذه_المقولة_تحتاج_مرجع_إلى_صفحة_محددة_أو_نطاق_من_الصفحات_تظهر_فيه_المقولة'"`UNIQ--nowiki-00000025-QINU`"'_(December_2021)">صفحة مطلوبة</span>]]</i>]</sup>_21-0|^]] Elon 2002, p. [صفحة مطلوبة].

- ^ أ ب ت Sachar, Howard M.: A History of the Jews in America – Vintage Books[صفحة مطلوبة]

- ^ Johnson, Paul (2009). A History of the Jews. Harper Collins. p. 395. ISBN 9780061828096.

- ^ Berghahn 1994, p. 102.

- ^ Berghahn 1994, pp. 105–106.

- ^ أ ب Kaplan, Marion (2004). Assimilation and Community. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 200–212.

- ^ Cohen, Robin; Cohen, Professor of Sociology at the University of Warwick and Currently Dean of Humanities Robin (2 November 1995). The Cambridge Survey of World Migration (in الإنجليزية). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44405-7.

- ^ Berghahn 1994, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Zimmerman, Andrew. Anthropology and antihumanism in imperial Germany. University of Chicago Press, 2010, p.292

- ^ "Introduction". Die Judischen Gefallenen. Archived from the original on 2 November 2004. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ Bryan Mark Rigg. Hitler's Jewish Soldiers: The Untold Story of Nazi Racial Laws and Men of Jewish Descent in the German Military (University Press of Kansas; 2002). Quote, p 72: "About 10,000 volunteered for duty, and over 100,000 out of a total German-Jewish population of 550,000 served during World War I. Some 78% saw front-line duty, 12,000 died in battle, over 30,000 received decorations, and 19,000 were promoted. Approximately 2,000 Jews became military officers and 1,200 became medical officers."

- ^ Grady 2017, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Mikics, David (9 July 2017). "The Jews Who Stabbed Germany in the Back". Tablet Magazine. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- ^ Grady 2017, p. 26.

- ^ A Page of Testimony given by Ermann's brother، في موقع ياد ڤاشم

- ^ Grady 2017, p. 33.

- ^ أ ب ت Crim, Brian E. (2018). "A Deadly Legacy: German Jews and the Great War". German History. 36 (2): 295–297. doi:10.1093/gerhis/ghx133.

- ^ Grady 2017, pp. 74–79.

- ^ Grady 2017, p. 86.

- ^ Strachan, Hew. The First World War: A New History. Simon and Schuster, 2014.[صفحة مطلوبة]

- ^ "Deutsche Jüdische Soldaten" (German Jewish soldiers) Bavarian National Exhibition

- ^ Bajohr, Frank (2006). "The 'Folk Community' and the Persecution of the Jews: German Society under National Socialist Dictatorship, 1933–1945". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 20 (2): 183–206. doi:10.1093/hgs/dcl001. قالب:Project MUSE.

- ^ Friedländer 2007, pp. 73–112.

- ^ Donald L. Niewyk, The Jews in Weimar Germany (2001)

- ^ Emily J. Levine (2013). Dreamland of Humanists: Warburg, Cassirer, Panofsky, and the Hamburg School. U of Chicago Press. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-226-06171-9.

- ^ Stirk, P. (1 March 2002). "Hugo Preuss, German political thought and the Weimar constitution". History of Political Thought. 23 (3): 497–516. JSTOR 26219879.

- ^ David Felix, Walther Rathenau and the Weimar Republic: the politics of reparations (1971).

- ^ Berghahn 1994, pp. 104–105.

- ^ أ ب Herzig, Prof em Dr Arno (5 August 2010). "1815–1933: Emanzipation und Akkulturation | bpb". bpb.de (in الألمانية). Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ Friedman, Jonathan C. (2007). "The Jewish Communities of Europe on the Eve of World War II". The Routledge History of the Holocaust. doi:10.4324/9780203837443.ch1. ISBN 978-0-203-83744-3.

- ^ Geller, Jay Howard (2012). "The Scholem Brothers and the Paths of German Jewry, 1914–1939". Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies. 30 (2): 52–73. doi:10.1353/sho.2012.0020. JSTOR 10.5703/shofar.30.2.52. S2CID 144015938. قالب:Project MUSE.

- ^ Niewyk, Donald L. (1975). "Jews and the Courts in Weimar Germany". Jewish Social Studies. 37 (2): 99–113. JSTOR 4466872.

- ^ Beer, Udo (1988). "The Protection of Jewish Civil Rights in the Weimar Republic: Jewish Self-Defense Through Legal Action". Leo Baeck Institute Year Book. 33: 149–176. doi:10.1093/leobaeck/33.1.149.

- ^ Kaplan, Edward K.; Dresner, Samuel H. (1998). Abraham Josua Heschel: Prophetic Witness. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 341. ISBN 0300071868.

- ^ Fraiman, Sarah (2000). "The Transformation of Jewish Consciousness in Nazi Germany as Reflected in the German Jewish Journal Der Morgen, 1925–1938". Modern Judaism. 20 (1): 41–59. doi:10.1093/mj/20.1.41. JSTOR 1396629. S2CID 162162089.

- ^ Mommsen, Hans (December 12, 1997). "Interview with Hans Mommsen" (PDF). Yad Vashem. Retrieved 2010-02-06.

- ^ Friedländer 2007, p. 59.

- ^ Friedländer 2007, p. 56 n.65.

- ^ Friedländer 2007, pp. 56, 59–60.

- ^ Aderet, Ofer (25 November 2011). "Setting the record straight about Jewish mathematicians in Nazi Germany". Haaretz. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

Except for a few individual cases, the mathematical society didn't care about the Jews. They collaborated with the state and with the party at every level. They took active steps and expelled the Jewish members even before they were compelled to—to be in step with the spirit of the times.

- ^ Hilberg, Raul (1995) [1992]. Perpetrators Victims Bystanders: The Jewish Catastrophe 1933–1945. London: Secker & Warburg. p. 66.

- ^ Harran, Marilyn J. (2000). The Holocaust Chronicles: A History in Words and Pictures. Lincolnwood, IL: Publications International. p. 384. Full text

- ^ Battegay, Caspar; Lubrich, Naomi (2018). Jewish Switzerland: 50 Objects Tell Their Stories (in الألمانية and الإنجليزية). Basel: Christoph Merian Verlag. pp. 158–161. ISBN 978-3-85616-847-6.

- ^ "Heydrich's secret instructions regarding the riots in November 1938". Simon Wiesenthal Center. Archived from the original on 7 August 2017.