كڤن رد

كڤن رد Kevin Rudd | |

|---|---|

الپورتريه الرسمي، 2023 | |

| سفير أستراليا رقم 23 لدى الولايات المتحدة | |

| تولى المنصب 20 March 2023 | |

| رئيس الوزراء | أنتوني ألبانيز |

| الحاكم العام | Quentin Bryce |

| سبقه | Arthur Sinodinos |

| رئيس وزراء أستراليا رقم 26 | |

| في المنصب 3 ديسمبر 2007 – 24 يونيو 2010 | |

| العاهل | إليزابث الثانية |

| النائب | جوليا گيلارد |

| الحاكم العام | Michael Jeffery Quentin Bryce |

| سبقه | جون هوارد |

| خلـَفه | جوليا گيلارد |

| زعيم حزب العمال | |

| في المنصب 26 يونيو 2013 – 13 سبتمبر 2013 | |

| النائب | أنطوني ألبانيز |

| سبقه | جوليا گيلارد |

| خلـَفه | بيل شورتن |

| في المنصب 4 ديسمبر 2006 – 24 يونيو 2010 | |

| Deputy | جوليا گيلارد |

| سبقه | كيم بيزلي |

| خلـَفه | جوليا گيلارد |

| وزير الشئون الخارجية | |

| في المنصب 14 سبتمبر 2010 – 22 فبراير 2012 | |

| رئيس الوزراء | جوليا گيلارد |

| سبقه | ستفن سميث |

| خلـَفه | بوب كار |

| زعيم المعارضة | |

| في المنصب 4 ديسمبر 2006 – 3 ديسمبر 2007 | |

| النائب | جوليا گيلارد |

| سبقه | كيم بيزلي |

| خلـَفه | برندان نلسون |

| عضو البرلمان الأسترالي عن {{{constituency_عضو البرلمان}}} | |

| في المنصب 3 أكتوبر 1998 – 22 نوفمبر 2013 | |

| سبقه | Graeme McDougall |

| خلـَفه | تري بتلر |

| 9th رئيس كومنولث الأمم | |

| في المنصب 27 يونيو 2013 – 18 سبتمبر 2013 | |

| الرئيس | إليزابث الثانية |

| سبقه | جوليا گيلارد |

| خلـَفه | توني أبوت |

| تفاصيل شخصية | |

| وُلِد | كڤن مايكل رد 21 سبتمبر 1957 نامبور، كوينزلاند، أستراليا |

| الحزب | العمال |

| الزوج | |

| الأنجال | 3 |

| التعليم | Marist College Ashgrove ثانوية ولاية نامور |

| المدرسة الأم | الجامعة الوطنية الأسترالية |

| الوظيفة | رئيس منظمة (المعهد الدولي للسلام) |

| المهنة | دبلوماسي سياسي |

| التوقيع | |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | الموقع الرسمي |

| ||

|---|---|---|

رئيس وزراء أستراليا

|

||

كڤن مايكل رد (و. 21 سبتمبر 1957)، هو سياسي أسترالي سابق وكان رئيس وزراء أستراليا رقم 26، خدم من ديسمبر 2007 حتى يونيو 2010 ومرة أخرى من يونيو إلى سبتمبر 2013. وكان زعيم حزب العمال الأسترالي.

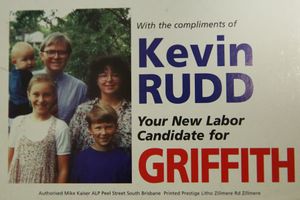

وُلد في نامبور، كوينزلاند. درس الدراسات الصينية في الجامعة الوطنية الأسترالية، ويتحدث المندرينية بطلاقة. قبل دخوله الحياة السياسية، عمل دبلوماسي، موظف سياسي، وموظف مدني. أُانتخب رد لعضوية مجلس النواب في انتخابات 1998، في تقسيم گريفيث. شارك في وزارة الظل عام 2001 حيث كان وزيراً للشئون الخارجية. في ديسمبر 2006، خلف كيم بيزلي ليصبح زعيم حزب العمال (ومن ثم زعيم المعارضة). في عهد رد، تفوق حزب العمال على حكومة التحالف الشاغرة بقيادة جون هوارد في استطلاعات الرأي، بعد إدلائه بعدد من التصريحات السياسية في التعليم، الصحة، العلاقات الصناعية، وتغير المناخ.

فاز حزب العمال في انتخابات 2007 بالأغلبية الساحقة، بفارق 23 مقعد. شهدت حكومة رد الأولى على التوقيع على پروتوكول كيوتو والاعتذار للشعوب الأصلية في أستراليا عن الأجيال المفقودة. وشملت سياساتها التوقيع على الشبكة الوطنية للنطاق العريض، ثورة التعليم الرقي، وبناء ثورة التعليم. قدمت الحكومة حزم تحفيز اقتصادية كاستجابة للأزمة المالية العالمية، وكانت أستراليا واحدة من البلدان الأكثر نموا التي نجحت في تجنب كساد أواخر عقد 2000.

By 2010, Rudd's leadership had faltered due to a loss of support among the Labor caucus and failure to pass key legislation like the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme. He resigned as prime minister in June 2010 after his deputy Julia Gillard challenged him in a leadership spill. He was replaced by Gillard as prime minister, who later appointed him as Minister for Foreign Affairs in her government. Leadership tensions between Rudd and Gillard continued, leading to Rudd resigning as Foreign Minister in February 2012 to unsuccessfully challenge her for the leadership of the party. After further leadership speculation, Rudd defeated Gillard in a final leadership ballot in June 2013, becoming prime minister for the second time. However, Labor were defeated in the 2013 election, ending his second term after only two months.

Rudd retired from parliament following the election, but he has stayed active in political discourse and academia, completing a DPhil at Jesus College, Oxford, in 2022. He has been involved in a number of international organizations, advocating for issues such as China–United States relations and Australian media diversity. He was appointed as Australia's Ambassador to the U.S. by the Albanese government in March 2023.

النشأة والتعليم

Rudd is of English and Irish descent.[3] His father's great-grandparents were English: Thomas Rudd and Mary Cable. Thomas had been convicted of stealing a bag of sugar, arriving in NSW on board the Earl Cornwallis in 1801.[4] Mary had been sentenced to transportation for stealing a bolt of cloth, arriving in the colony in 1804.[5] His mother's grandparents, Owen Cashin and Hannah Maher, who were both born in Ireland, met and married in Brisbane in 1887.[6]

Rudd was born in Nambour, Queensland, to Albert ("Bert") and Margaret (née DeVere) Rudd, the youngest son of four children, and grew up on a dairy farm in nearby Eumundi.[7][8] At an early age (5–7), he contracted rheumatic fever and spent a considerable time at home convalescing. It damaged his heart, in particular the valves, for which he has thus far had two aortic valve replacement surgeries, but this was discovered only some 12 years later.[9] Farm life, which required the use of horses and guns, is where he developed his lifelong love of horse riding and shooting clay targets.[10] He attended Eumundi State School.[11]

When Rudd was 11, his father, a share farmer and Country Party member, died. Rudd states that the family was required to leave the farm amidst financial difficulty between two and three weeks after the death, though the family of the landowner states that the Rudds didn't have to leave for almost six months.[12] Following this traumatic childhood and despite familial connections with the Country Party, Rudd joined the Australian Labor Party in 1972 at the age of 15.[13]

Rudd boarded at Marist College Ashgrove in Brisbane,[14] although these years were not happy due to the indignity of poverty and reliance on charity; he was known to be a "charity case" due to his father's sudden death. He has since described the school as "tough, harsh, unforgiving, institutional Catholicism of the old school".[9] Two years later, after she retrained as a nurse, Rudd's mother moved the family to Nambour, and Rudd rebuilt his standing through study and scholastic application[9] and was dux of Nambour State High School in 1974.[15] In that year, he was also the state winner of the "Youth Speaks for Australia" public speaking competition sponsored by the Jaycees.[16] His future Treasurer Wayne Swan attended the same school at the same time, although they did not know each other as Swan was three years ahead.[15]

Rudd studied at the Australian National University in Canberra, where he resided at Burgmann College and graduated with Bachelor of Arts (Asian Studies) with First-Class Honours. He majored in Chinese language and Chinese history, and became proficient in Mandarin. His Chinese name is Lù Kèwén (الصينية المبسطة: 陆克文; الصينية التقليدية: 陸克文).[17] Rudd completed his BA in 1978, deferring his honours component for a year during which time he took a study trip to Taiwan. He also volunteered as a research assistant with the Zadok Institute for Christianity and at a St Vincent de Paul drug rehabilitation centre.[18]

Rudd's thesis on Chinese democracy activist Wei Jingsheng[19] was supervised by Pierre Ryckmans, the eminent Belgian-Australian sinologist.[20] During his studies, Rudd did housecleaning for political commentator Laurie Oakes to earn extra money.[21] In 1980 he continued his Chinese studies at the Mandarin Training Center of National Taiwan Normal University in Taipei, Taiwan. Delivering the 2008 Gough Whitlam Lecture at the University of Sydney on The Reforming Centre of Australian Politics, Rudd praised the former Labor Prime Minister for implementing educational reforms, saying he was:

... a kid who lived Gough Whitlam's dream that every child should have a desk with a lamp on it where he or she could study. A kid whose mum told him after the 1972 election that it might just now be possible for the likes of him to go to university. A kid from the country of no particular means and of no political pedigree who could therefore dream that one day he could make a contribution to our national political life.[22]

السيرة الدبلوماسية المبكرة

Rudd joined the Department of Foreign Affairs in 1981 as a graduate trainee. His first posting was as Third Secretary at the Australian Embassy in Stockholm from November 1981 to December 1983 where he organised an Australian film festival, represented Australia at the Stockholm Conference on Acidification of the Environment, and reported on Soviet gas pipelines and European energy security.[23][صفحة مطلوبة] In 1984, Rudd was appointed Second Secretary at the Australian Embassy in Beijing, and promoted to First Secretary in 1985, where he was responsible for analysing Politburo politics, economic reform, arms control and human rights under Ross Garnaut, David Irvine and Geoff Raby.[23][صفحة مطلوبة] He returned to Canberra in 1987 and was assigned to the Policy Planning Branch, then the Staffing Policy Section, and was selected to serve as the Office of National Assessments Liaison Officer at the Australian High Commission in London commencing in 1989 but declined.[24]

دخول معترك السياسة

عضوية البرلمان (1998–2007)

وزارة الظل (2001–06)

زعيم المعارضة (2006–07)

انتخابات 2007

رئاسة الوزاراء الأولى (2007–10)

السياسات الداخلية

البيئة

الأجيال المسروقة

As the parliament's first order of business, on 13 February 2008, Rudd gave a national apology to Indigenous Australians for the stolen generations. The apology, for the policies of successive parliaments and governments, passed unanimously as a motion by both houses of parliament.[25] Rudd pledged the government to bridging the gap between Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Australian health, education and living conditions, and in a way that respects their rights to self-determination.[26] During meetings held in December 2007 and March 2008 the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) adopted six targets to improve the wellbeing of Indigenous Australians over the next five to twenty years. As of 2016, there have been eight Closing the Gap Reports presented to Parliament, providing data in areas that previously had none and updates on progress.[27]

Since leaving politics, Rudd has established the Australian National Apology Foundation, as foreshadowed in his final speech to Parliament,[28] to continue to promote reconciliation and closing the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.[29] He has contributed $100,000 to the Foundation and to kickstart fundraising for a National Apology Chair at the Australian National University.[30]

الاقتصاد

قمة أستراليا 2020

العلاقات الاقتصادية

التعليم

الهجرة

الضرائب

الرعاية الصحية

الأسرة

المعاقون

الشئون الخارجية

أراضي الهادي

العراق

أفغانستان

المواقف السياسية

الأمة

المجتمع

الاستقالة

انتخابات 2010

الشعبية والتقييم

Rudd maintained long periods of popularity in opinion polls during his initial tenure as prime minister for his management of the 2008 financial crisis and his well renowned apology to the Indigenous community,[31][32][33] achieving some of the highest approval ratings for an Australian prime minister on record during the height of the 2008 financial crisis.[34][35] However, he would see a rapid decrease in popularity after his failed handling of legislative negotiations, ultimately leading to the demise of his premiership. The circumstances of his removal from office have remained controversial; his supporters have decried the undemocratic nature of his ousting, while critics have accused him of an autocratic and flawed leadership style.[36][37][38][39] He is often ranked in the middle-to-lower tier of Australian prime ministers.[40][41][42]

وزير الخارجية (2010–2012)

Prime Minister Julia Gillard appointed Rudd as Minister for Foreign Affairs in Cabinet on 14 September 2010.[43][44] He represented Gillard at a UN General Assembly meeting in September 2010.[45]

WikiLeaks, in 2010, published material about Kevin Rudd's term as prime minister, included United States diplomatic cables leak. As foreign minister, Rudd denounced publishing classified documents by WikiLeaks. The Australian media reported that references to Rudd in the cables included frank discussions between Rudd and US officials about China and Afghanistan. This included negative assessments of some of Rudd's foreign policy initiatives and leadership style, written in confidence for the US Government by the US Embassy staff in Australia.[46][47][48]

Before his first visit to Israel as foreign minister, Rudd stated Israel should be subject to International Atomic Energy Agency inspection. Israeli Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman rejected the call.[49][50]

Following the 2011 Egyptian revolution and resignation of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, Rudd called for "constitutional reform and a clear timetable towards free and fair elections".[51]

In response to the 2011 Libyan civil war, Rudd announced in early March 2011, the international community should enforce a no-fly zone, as the "lesser of two evils". The US officials in Canberra sought clarification on what the Australian Government was proposing. Gillard said the United Nations Security Council should consider a full range of alternatives, and that Australia was not planning to send forces to enforce a no-fly zone.[52]

Following the devastating 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan, Rudd announced after talking with Japanese Foreign Minister Takeaki Matsumoto, he had offered Australian field hospitals and disaster victim identification teams to help with recovery. Rudd also said he had offered Australian atomic expertise and sought urgent briefings following an explosion at a nuclear plant.[53] Rudd announced his resignation as foreign minister on 22 February 2012, citing Gillard's failure to counter character attacks launched by Simon Crean and "other faceless men" as his reasons. Speaking to the press, Rudd explained that he considered Gillard's silence as evidence that she no longer supported him, and therefore he could not continue in office. "I can only serve as Foreign Minister if I have the confidence of Prime Minister Gillard and her senior ministers," he said.[54][55][56]

Rudd resigned as the Minister for Foreign Affairs followed heated speculation about a possible leadership spill. Craig Emerson temporarily replaced Rudd as Minister for Foreign Affairs, until Senator Bob Carr became Minister for Foreign Affairs on 13 March 2012.[57]

توترات الزعامة

رئاسة الوزراء الثانية (2013)

انتخابات 2013

ما بعد رئاسة الوزراء (2013–الحاضر)

الاستقالة من البرلمان

On 13 November 2013, Rudd announced that he would soon resign from Parliament.[58] In his valedictory speech to the House of Representatives, Rudd expressed his attachment to his community but said he wanted to dedicate more time to his family and minimise disruption to House proceedings.[28][59] Rudd submitted his resignation in writing to the Speaker, Bronwyn Bishop, on 22 November 2013, formally ending his parliamentary career.[60] Terri Butler was selected to run for the Labor Party at the resulting by-election in the electorate of Griffith to be held on 8 February 2014.[61] Rudd offered Butler his support and advice, and campaigned with her in a low-key appearance on 11 January 2014.[62][63] Butler ultimately succeeded Rudd in the seat.[64]

الأدوار الدولية

In early 2014, Rudd left Australia to work in the United States, where he was appointed a Senior Fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School's Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he completed a major research effort on the future of US-China relations.[65] Through 2014 Rudd joined the Center for Strategic and International Studies as a distinguished statesman,[66] and was appointed a distinguished fellow at both the Paulson Institute at the University of Chicago, Illinois[67] and Chatham House, London.[68]

In September of that year, he was appointed Chair of the Independent Commission on Multilateralism at the International Peace Institute in Vienna, Austria,[69] and in October became the first president of the Asia Society Policy Institute in New York City.[70]

On 5 November 2015, Rudd was appointed to chair Sanitation and Water For All, a global partnership to achieve universal access to drinking water and adequate sanitation.[71] He has also actively contributed to the World Economic Forum's Global Agenda Council on China.[72] Rudd is also a member of the Berggruen Institute's 21st Century Council.[73] On 21 October 2016, he was awarded an honorary professorship at Peking University.[74]

In 2016, Rudd asked the Government of Australia (then a government of the Liberal-National Coalition) to nominate him for Secretary-General of the United Nations. At its meeting on 28 July, the Cabinet was divided on his suitability for the role and, on that basis, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull decided to decline the request; since nomination by the Australian government was considered a necessary prerequisite for candidacy, Turnbull's decision essentially ended Rudd's campaign;[75][76][77] Rudd later confirmed as much.[78] However, there remains dispute over what if any earlier assurances Turnbull may have given to Rudd and about what happened in the Cabinet meeting.[79][80][81]

Rudd is also a member of the Global Leadership Foundation, a non-profit organisation comprising a network of former heads of state or government.[82][83]

Academic

In 2017, Rudd began studying for a doctorate on Xi Jinping at Jesus College, Oxford.[84] In 2022, Rudd was conferred with a Doctorate of Philosophy from the University of Oxford. In his thesis, titled "China's new Marxist nationalism: defining Xi Jinping's ideological worldview",[85] Rudd argues that Xi has adopted a more Marxist political and economic approach to government and that will have negative consequences for economic growth and China as a whole.[86]

Ambassador to the United States

In late 2022, there were calls for Rudd to be appointed as the next Australian Ambassador to the United States.[87] On 20 December 2022, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong announced that Rudd would be appointed as the 23rd Ambassador of Australia to the United States in early 2023, succeeding Arthur Sinodinos.[88] Rudd assumed the position on 20 March 2023.[89]

In March 2024, Rudd was criticised by former US president Donald Trump, who labelled him "nasty" and indicated that he would be removed as ambassador to the US should Trump win the 2024 presidential election. Rudd had previously been highly critical of Trump during his first presidency.[90][91] Penny Wong later clarified that Rudd would stay on as ambassador even in the result of Trump winning the election.[92]

In the role, Rudd has been a vocal advocate for AUKUS security partnership, urging American decision makers to implement its promise of technology sharing.[93] While it was hoped he might defuse tension between the United States and China in the role, Rudd has become a blunt critic of China's expansionism.[94]

Writings

Rudd has authored several books. While prime minister, he co-authored a children's book with entertainer Rhys Muldoon, Jasper & Abby and the Great Australia Day Kerfuffle, which was published in 2010.[95] In October 2017, Rudd launched the first volume of his autobiography, entitled Not for the Faint-hearted: A Personal Reflection on Life, Politics and Purpose, which chronicles his life until becoming prime minister in 2007.[96] The following year, he published the second volume of his autobiography, The PM Years, which covers his prime ministership, the events leading to his removal, and his subsequent return to the position in 2013.[97]

In March 2021, Rudd published The Case for Courage as part of Monash University Publishing's In the National Interest series. The book details Rupert Murdoch's domination of the Australian media landscape and poses ideas for how the Labor Party can ensure longevity in office.[98] His next book, The Avoidable War, focuses on the bilateral relationship between the United States and China and how the two nations can avoid conflict.[99]

Personal life

In 1981, Rudd married Thérèse Rein whom he had met at a gathering of the Australian Student Christian Movement during his university years. Both were residents at Burgmann College during their first year of university.[100] Rudd and Rein have three children.[101][102] Rudd is a supporter of the Brisbane Lions.[103]

In 2011, Rudd won a tea-making competition in a competition to create Twinings' Australian Afternoon variety and announced that the proceeds from the sales of this blend will be donated to the RSPCA.[104] In 2016, Twinings stopped donating the proceeds from the sales of this tea variety to the RSPCA.[105]

Religion

Rudd and his family attend the Anglican church of St John the Baptist in Bulimba in his electorate. Although raised a Roman Catholic, Rudd was actively involved in the Evangelical Union while studying at the Australian National University,[106] and he began attending Anglican services in the 1980s with his wife.[13] In December 2009, Rudd attended a Catholic Mass to commemorate the canonisation of Mary MacKillop at which he received Holy Communion. Rudd's actions provoked criticism and debate among both political and religious circles.[107] A report by The Australian quoted that Rudd embraced Anglicanism but at the same time did not formally renounce his Catholic faith.[108]

Rudd was a mainstay of the parliamentary prayer group in Parliament House, Canberra.[109] He has been vocal about his Christianity and has given a number of prominent interviews to the Australian religious press on the topic.[110] Rudd has defended church representatives engaging with policy debates, particularly with respect to WorkChoices legislation, climate change, global poverty, therapeutic cloning, and asylum seekers.[111] In 2003, he described himself as "an old-fashioned Christian socialist".[112][113] In a 2006 essay in The Monthly,[111] he argued:

A [truly] Christian perspective on contemporary policy debates may not prevail. It must nonetheless be argued. And once heard, it must be weighed, together with other arguments from different philosophical traditions, in a fully contestable secular polity. A Christian perspective, informed by a social gospel or Christian socialist tradition, should not be rejected contemptuously by secular politicians as if these views are an unwelcome intrusion into the political sphere. If the churches are barred from participating in the great debates about the values that ultimately underpin our society, our economy and our polity, then we have reached a very strange place indeed.

He cites Dietrich Bonhoeffer as a personal inspiration in this regard.[114]

When in Canberra, Rudd and Rein worshipped at St John the Baptist Church, Reid, where they were married.[9] Rudd often did a "door stop" interview for the media when leaving the church yard.[115]

Health

In 1993, Rudd underwent a cardiac valve transplant operation (Ross procedure), receiving a cadaveric aortic valve replacement for rheumatic heart disease.[116] In 2011, Rudd underwent a second cardiac valve transplant operation,[117] making a full recovery from the surgery.[118][119]

Published works

- Rudd, Kevin (2009). Building on ASEAN's Success: Towards an Asia Pacific Community. Singapore: ISEAS Publishing. ISBN 978-9812308719.[120]

- Rudd, Kevin (2017). Not for the Faint-hearted: A Personal Reflection on Life, Politics and Purpose. Sydney: Pan Macmillan Australia. ISBN 9781743534830.

- Rudd, Kevin (2018). The PM Years. Sydney: Pan Macmillan Australia. ISBN 9781760556686.

- Rudd, Kevin (2021). The Case for Courage. Melbourne: Monash University Publishing. ISBN 9781922464156.

- Rudd, Kevin (2022). The Avoidable War: The Dangers of a Catastrophic Conflict between the US and Xi Jinping's China. PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1541701298.

- Rudd, Kevin (2024). On Xi Jinping: How Xi's Marxist Nationalism is Shaping China and the World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0197766033.

انظر أيضاً

- حكومة رد (2007–10)

- حكومة رد (2013)

- وزارة رد الأولى

- وزارة رد الثانية

- وزارة گيلارد الأولى

- قائمة رؤساء وزراء الملكة إليزابث الثانية

المصادر

- ^ Rudd, Kevin (8 May 2005). "Kevin Rudd: The God Factor". Compass (Interview). Interviewed by Geraldine Doogue. ABC1.

I come from a long history of people who have spoken about the relevance of their faith to their political beliefs, on our side of politics going back. I mean here in Queensland Andrew Fisher was the Labor Prime Minister from this State. Andrew Fisher was a Christian Socialist. He taught Presbyterian Sunday School. He in turn came out of the stable of Keir Hardie who was himself a Presbyterian Sunday School teacher who founded the British Labour Party in the 1890s and was the first British Labour member of parliament. There's a long tradition associated with this; currently called the Christian Socialist Movement. And it's a worldwide network of people. The fact that you don't often hear from us in this country, well it's open for others to answer. I'm a relatively recent arrival. But I think, I think given what's happening on the political right in this country, what's happening on the political right in America, it's important that people on the centre-left of politics begin to argue a different perspective from within the Christian tradition.

{{cite interview}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|subjectlink=(help) - ^ Maiden, Samantha (16 December 2009). "Rudd's decision to take holy communion at Catholic mass causes debate". The Australian. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ^ Maiden, Samantha (31 July 2008). "Urchins, convicts at root of Kevin Rudd's family tree". The Australian. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ^ "Australia Day and your Convict Ancestor". History Services Blog. 26 January 2010. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ^ Elder, John (20 January 2008). "With family like this, some Rudd's going to stick". The Age (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ Zwartz, Barney (31 July 2008). "So, Prime Minister, you're related to a thief and a forger". The Sydney Morning Herald (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ Macklin 2007

- ^ "Kevin Rudd: before office". National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 24 September 2025.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Marr, David (7 June 2010). "We need to talk about Kevin ... Rudd, that is" (An edited extract of Power Trip: The Political Journey of Kevin Rudd, published in Quarterly Essay, p. 38, by Black Inc Books). The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ^ "PM reveals inner cowboy". The Sydney Morning Herald. 19 September 2008. Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- ^ "Kevin Rudd: Before office". Australia's Prime Ministers. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ Duff, Eamonn; Walsh, Kerry-Anne (11 March 2007). "A disputed eviction and a tale of family honour". The Sun-Herald. Archived from the original on 12 March 2007. Retrieved 11 March 2007.

- ^ أ ب Marriner, Cosima (9 December 2006). "The lonely road to the top". The Sydney Morning Herald. p. 33. Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2007.

- ^ Marriner, Cosima (27 April 2007). "It's private – the school he wants to forget". The Sydney Morning Herald. p. 1. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ أ ب "Genesis of an ideas man". The Australian. 5 December 2006. Archived from the original on 25 November 2007. Retrieved 5 December 2006.

- ^ "Youth wins". Noosa News. 1 August 1974. Archived from the original on 12 July 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- ^ Garnaut, John (26 November 2007). "China's leaders slow to tackle inflation". The Sydney Morning Herald.[dead link]; McDonald, Hamish (1 December 2007). "Tough role, especially as the boss is the diplomat". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 5 January 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2020.; Chou, Jennifer (3 December 2007). "Kevin Rudd, aka Lu Kewen". The Weekly Standard. Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2007.; "A man of reason and foresight takes the reins". China Daily. Beijing, China. 4 December 2007. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ^ "2 chosen from ACT for youth conference". Canberra Times. 16 September 1979. Archived from the original on 12 July 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- ^ Brown, Rachel (9 April 2008). "Chinese activist puts hope in Rudd" (transcript). PM. Australia: ABC Radio. Archived from the original on 19 December 2022. Retrieved 14 April 2008.

- ^ Stuart, Nicholas (2007). Kevin Rudd: An Unauthorised Political Biography. Scribe. ISBN 9781921215582.

- ^ Overington, Caroline (9 December 2006). "McKew impressed to the max". The Australian. Archived from the original on 14 September 2007. Retrieved 4 March 2007.

- ^ Murphy, Katharine (13 September 2008). "Rudd pays tribute to his hero Whitlam". The Age. Melbourne. Archived from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2010.; "Dithering Liberals get their deserts". The Sydney Morning Herald. 13 September 2008. Archived from the original on 15 September 2008. Retrieved 19 September 2010.

- ^ أ ب Weller, Patrick (2014). Kevin Rudd: Twice Prime Minister. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 978-0522857481.

- ^ Rudd, Kevin (2017). Not for the Faint-hearted: A Personal Reflection on Life, Politics and Purpose 1957–2007. Sydney: Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-1743534830.

- ^ "The Apology: ABC News". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 16 February 2008. Archived from the original on 10 October 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2010.; "Apology to Australia's Indigenous Peoples". Australian Parliament. 13 February 2008. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2016.; Burgess, Matthew; Rennie, Reko (13 February 2008). "Tears in Melbourne as PM delivers apology". The Age. Archived from the original on 4 January 2009. Retrieved 13 February 2008.; "Speech by Kevin Rudd to the Parliament: 13 February 2008". Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Archived from the original on 2 October 2008. Retrieved 21 November 2016.; "Thousands greet Stolen Generations apology". ABC News Online. ABC. 13 February 2008. Archived from the original on 20 February 2008. Retrieved 13 February 2008.; "Cheers, tears as Rudd says 'sorry'". ABC Online. 13 February 2008. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ "Govt promises action after apology". ABC News. ABC. 13 February 2008. Archived from the original on 17 February 2008. Retrieved 13 February 2008.; Calma, Tom (24 September 2008). "UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: Australia should sign". Koori Mail. No. 435. Lismore, NSW: Budsoar. p. 27.

- ^ Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet (2016). "Closing the Gap: Prime Minister's Report 2016". Archived from the original on 11 February 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ أ ب Kevin Rudd (14 November 2013). "Kevin Rudd's full resignation speech". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ Atfield, Cameron (7 February 2014). "Kevin Rudd announces National Apology Foundation". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ "Kevin Rudd Announces Donation To Establish 'Close The Gap' Chair at ANU". Huffington Post Australia. 11 November 2015. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2016.; "Former PM Rudd donates $100,000 to ANU Apology Chair (media release)". Australian National University. 11 November 2015. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ Bongiorno, Frank (18 November 2013). "How will history judge Kevin Rudd". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 2 May 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- ^ Mao, Frances (13 February 2018). "Australia's apology to Stolen Generations: 'It gave me peace'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ Marr, David (27 June 2013). "Kevin Rudd: a man for the party but not a party man". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 September 2013. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- ^ "Kevin Rudd's polling since 2006". Australian Financial Review. 24 June 2010. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Coorey, Philip (30 March 2009). "The Rudd supremacy". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 24 September 2018. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- ^ Soutphommasane, Tim (24 June 2010). "Why Labor ditched Kevin Rudd". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 September 2013. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Marr, David (7 June 2010). "We need to talk about Kevin ... Rudd, that is". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ^ "Kevin Rudd's successes and failures". Australian Financial Review. 24 June 2010. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Knott, Matthew (14 November 2013). "The Rudd years: highs and lows". Crikey. Archived from the original on 17 November 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ^ Mackerras, Malcolm (25 June 2010). "Ranking Australia's prime ministers". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 25 October 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Strangio, Paul (2013). "Evaluating Prime-Ministerial Performance: The Australian Experience". In Strangio, Paul; 't Hart, Paul; Walter, James (eds.). Understanding Prime-Ministerial Performance: Comparative Perspectives. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199666423.

- ^ Strangio, Paul (February 2022). "Prime-ministerial leadership rankings: the Australian experience". Australian Journal of Political Science. 57 (2): 180–198. doi:10.1080/10361146.2022.2040426. S2CID 247112944. Archived from the original on 21 February 2024. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ "Rudd nabs Foreign Affairs portfolio". ABC News. Australia. 11 September 2010. Archived from the original on 13 September 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- ^ "Governor-General swears in new ministry". ABC News. Australia. 14 September 2010. Archived from the original on 16 September 2010. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ Coorey, Phillip (14 September 2010). "Rudd to represent Gillard at annual UN meeting". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 18 September 2010. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ^ "Rudd shrugs off 'control freak' cable". Australia: ABC News. 8 December 2010. Archived from the original on 2 February 2011. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- ^ Maley, Paul (5 December 2010). "Kevin Rudd's plan to contain Beijing". The Australian. Archived from the original on 20 January 2011. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- ^ Yaxley, Louise (10 December 2010). "Afghanistan 'scared the hell' out of Rudd". Australia: ABC News. Archived from the original on 27 January 2011. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- ^ Lyons, John (14 December 2010). "Rudd calls for inspections of Israel's nuclear facility". The Australian. Retrieved 13 May 2011.

- ^ Fay Cashman, Greer (14 December 2010). "Lieberman rejects Rudd's calls for Israel to sign NPT". The Jerusalem Post. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 13 May 2011.

- ^ "Gillard, Rudd call for election timetable to steer new Egypt". The Australian. Australian Associated Press. 12 February 2011. Archived from the original on 13 February 2011. Retrieved 13 May 2011.

- ^ Grattan, Michelle; Koutsoukis, Jason (11 March 2011). "Gillard, Rudd at odds on Libya". The Age. Melbourne. Archived from the original on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 13 May 2011.

- ^ "Kevin Rudd says world needs urgent briefings on nuclear threat in Japan". The Australian. AAP, AFP. 13 March 2011. Retrieved 13 May 2011.

- ^ "Former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd resigns as Foreign Minister". PerthNow. Australian Associated Press. 22 February 2012. Archived from the original on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Rudd resigns as foreign minister". World News Australia. Australian Associated Press. 22 February 2012. Archived from the original on 9 December 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ Benson, Simon (23 February 2012). "Kevin Rudd had dinner with Kim Beazley before all hell broke loose". The Daily Telegraph. Australia. Archived from the original on 23 February 2012. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ^ "Emerson takes foreign reins". The Sydney Morning Herald. 23 February 2012. Archived from the original on 21 February 2024. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ Murphy, Katharine (13 November 2013). "Kevin Rudd quits politics". Guardian Australia. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ "Former prime minister Kevin Rudd quits federal politics with emotional speech to Parliament". ABC Online. 14 November 2013. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ Swan, Jonathon (22 November 2013). "With formal resignation, Kevin Rudd irritates Coalition one more time". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ Swan, Jonathan (22 November 2013). "With formal resignation, Kevin Rudd irritates Coalition one more time". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 23 November 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ Brennan, Rose (16 December 2013). "Kevin Rudd promises advice to Griffith Labor candidate Terri Butler". The Courier-Mail. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2006.

- ^ Vogler, Sarah (16 January 2014). "Bill Shorten to campaign in Griffith for Terri Butler days after Kevin Rudd quietly lent a hand". The Courier-Mail. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ "The official election results". Griffith by-election 2014. Australian Electoral Commission. 27 February 2014. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ "Kevin Rudd goes to Harvard". The Sydney Morning Herald. 21 February 2014. Archived from the original on 18 July 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ Center for Strategic and International Studies (11 June 2014). "Former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd Joins CSIS as Distinguished Statesman". Archived from the original on 20 December 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ Bramston, Troy (12 September 2014). "Distinguished fellow Rudd adds another string to bow". The Australian. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

* "Paulson Institute welcomes former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd as its first Distinguished Fellow". Paulson Institute. 11 September 2014. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

* Huang, Wen (14 October 2014). "Former Australian prime minister joins Paulson Institute as distinguished fellow". University of Chicago. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016. - ^ Miller, Nick (13 November 2013). "Former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd appointed to Chatham House". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 24 February 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

* Chatham House (20 June 2014). "Kevin Rudd Joins Chatham House as a Distinguished Visiting Fellow". Archived from the original on 18 April 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016. - ^ "Kevin Rudd, Former Australian PM, to Chair Independent Commission on Multilateralism". International Peace Institute. 22 September 2014. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

* "Rudd to chair global security review". The Australian. Australian Associated Press. 24 September 2014. Archived from the original on 7 November 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2016. - ^ O'Malley, Nick (18 February 2015). "Kevin Rudd makes debut as president of Asia Society Policy Institute". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

* Asia Society (21 October 2014). "Kevin Rudd, Former Australian PM, to Head Asia Society Policy Institute". Archived from the original on 21 March 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016. - ^ Cox, Lisa (6 November 2015). "Higher ambitions in sight? Kevin Rudd appointed to water and sanitation role with UN partner". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ Rudd, Kevin (2015). "Outlook on the Global Agenda 2015. Regional Challenges: Asia". Outlook on the Global Agenda 2015. Archived from the original on 18 April 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ "Berggruen Institute". Archived from the original on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ Zhu Jieyun (Jane) (21 October 2016). "The 26th Prime Minister of Australia Kevin Rudd Receives Honorary Professorship and Speaks at PKU". Peking University. Archived from the original on 5 November 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ Anderson, Stephanie (18 July 2016). "Julie Bishop confirms Kevin Rudd seeking nomination for UN Secretary-General election". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 18 July 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ^ Hunter, Fergus (18 July 2016). "Nominate me: Kevin Rudd seeks government support to be United Nations boss". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 18 July 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ^ Murphy, Katharine (29 July 2016). "Malcolm Turnbull refuses to nominate Kevin Rudd as UN secretary general". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ Grattan, Michelle (29 July 2016). "Turnbull kills Rudd's UN secretary-general bid". The Conversation. The Conversation Media Group Ltd. Archived from the original on 24 October 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ^ Hunter, Fergus (3 August 2016). "Did Barnaby Joyce mislead Australia? The questions the government needs to answer over Kevin Rudd". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- ^ Karp, Paul (5 August 2016). "Kevin Rudd says Malcolm Turnbull's rejection of UN bid a 'monstrous intrusion'". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

- ^ Wyeth, Grant (1 August 2016). "Why Did Turnbull Decide Against Endorsing Rudd for UN Secretary General?". The Diplomat. Diplomat Media Inc. Archived from the original on 24 October 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ^ "Home". Global Leadership Foundation. Archived from the original on 24 September 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- ^ "Kevin Rudd". Global Leadership Foundation. Archived from the original on 5 September 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- ^ Dry, Will (16 October 2017). "New Jesus fresher: Ex-Australian PM Kevin Rudd". Cherwell. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- ^ Rudd, Kevin. "China's new Marxist nationalism: defining Xi Jinping's ideological worldview". Oxford University Research Archive. Oxford University. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ Galloway, Anthony (11 September 2022). "Sydney Morning Herald". Nine Newspapers. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ Knott, Matthew (23 October 2022). "'Clout, access, gravitas': Push for Kevin Rudd to be named US ambassador". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ^ Evans, Jake (20 December 2022). "Former prime minister Kevin Rudd posted to Washington as Australia's new US ambassador". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ^ Macmillan, Jade (21 March 2023). "Arthur Sinodinos finishes as ambassador to the US as it reckons with the prospect of another Donald Trump presidency". ABC News. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ Butler, Josh (20 March 2024). "Donald Trump calls Kevin Rudd 'nasty' and says he 'won't be there long' as Australia's ambassador to US". Guardian Australia. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ bbc.com 20 October 2025: Trump to Australian ambassador: 'I don't like you either'

- ^ "Australia defends its US ambassador, Kevin Rudd, after Trump attack". Reuters. 20 March 2024. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ "Rudd slams 'crazy' US red tape slowing AUKUS". Australian Financial Review (in الإنجليزية). 12 October 2023. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ Nielsen, Annelise (22 November 2023). "Kevin Rudd's shifting sentiment towards China could bolster AUKUS pact". skynews (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ Flood, Alison (4 January 2010). "Australia's PM writes children's book about his pets". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ King, Madonna (24 October 2017). "Public frenemies: Kevin Rudd's ruthless review of his Labor mates". Brisbane Times. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ Hewett, Jennifer (23 October 2018). "Former PM Kevin Rudd's hit list hits home". Australian Financial Review. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ "The Case for Courage - Kevin Rudd". Monash University Publishing. March 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ Crabtree, James (2 May 2022). "The Avoidable War — averting a conflict between the US and China". Financial Times. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ^ "Thérèse Rein". National Archives of Australia. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ^ Hayes, Liz (15 April 2007). "Team Rudd". Sixty Minutes. Archived from the original on 10 April 2012.

- ^ "Rudd walks daughter down the aisle". The Age. Melbourne. Australian Associated Press. 5 May 2007. Retrieved 25 November 2007.; Zwartz, Barney (9 December 2006). "ALP's new man puts his faith on display". The Age. Melbourne. Retrieved 9 December 2006.; Egan, E. (3 December 2006). "Kevin Rudd". The Age. Melbourne. Retrieved 26 October 2007.

- ^ McNicol, Adam (24 June 2010). "Dogs celebrate fan Gillard's ascension to PM". afl.com.au. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- ^ AAP (23 August 2011). "Kevin Rudd wins Twinings tea challenge". news.com.au. Archived from the original on 16 August 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2025.

- ^ AAP (2 April 2016). "Kevin Rudd calls out Twinings for stopping fundraising deal with RSPCA". 9news.com.au. Archived from the original on 29 May 2025. Retrieved 29 May 2025.

- ^ Tom Stayner. "Our man in the Lodge." Woroni. 28 February – 12 March 2008.

- ^ Veness, Peter (14 December 2009). "Mary MacKillop "likely" to become saint". The Sydney Morning Herald.; "Rudd 'exploiting MacKillop sainthood': Abbott". Herald Sun. Australian Associated Press. 14 December 2009.

- ^ Maiden, Samantha (16 December 2009). "Rudd's decision to take holy communion at Catholic mass causes debate". The Australian.

- ^ "Abbott attacks Rudd on religion in politics". The Age. Melbourne. 27 January 2007. Retrieved 26 November 2007.

- ^ Woodall, Helen (November 2003). "Kevin Rudd talks about his faith". The Melbourne Anglican. Archived from the original on 25 September 2006. Retrieved 4 December 2006.; Egan, Carmel (3 December 2006). "Kevin Rudd". The Age. Melbourne. Retrieved 4 December 2006.

- ^ أ ب Rudd, Kevin (October 2006). "Faith in Politics". The Monthly. pp. 22–30.; Rudd, Kevin (26 October 2005). "Christianity and Politics" (PDF). p. 9.[dead link] ; "Anglican leader joins IR debate". ABC News. 11 July 2005. Archived from the original on 19 June 2007. Retrieved 4 December 2006.

- ^ Edwards, Verity; Maiden, Samantha (15 December 2006). "Rudd backtracks on socialist label". The Australian. Archived from the original on 6 September 2007. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ Crabb, Annabel (3 September 2013). "Call yourself a Christian: private faith, public politics". ABC. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ "Tony Jones speaks to Kevin Rudd". Lateline. 2 October 2006. Retrieved 4 December 2006.

- ^ Kevin Rudd's politics of piety put on parade, Dennis Atkins, The Courier-Mail, 26 December 2009. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ^ Rudd, Kevin (20 July 2011). "Aortic valve replacement". Australian Minister for Foreign Affairs.

- ^ Packham, Ben; Kelly, Joe (20 July 2011). "Kevin Rudd to have heart surgery". The Australian. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ Madigan, Michael (6 August 2011). "Kevin Rudd bounces back from heart surgery with new home, and maybe new grandchildren". The Courier-Mail.

- ^ Dunlevy, Sue (21 July 2011). "Rudd's second heart valve replacement riskier". The Australian.

- ^ Contains the text of the ""29th Singapore Lecture"" delivered by Kevin Rudd, then Prime Minister of Australia, on 12 August 2008.

المراجع

- Crabb, Annabel (2010). Rise of the Ruddbot:Observations from the Gallery. Melbourne: Black Inc. ISBN 978-1-86395-483-9.

- Hartcher, Peter (2009). To the Bitter End : The Dramatic Story of the Fall of John Howard and the Rise of Kevin Rudd. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74175-623-4.

- Paul Kelly, Triumph and Demise: The Broken Promise of a Labor Generation, Melbourne University Press, 2014. ISBN 9780522862102 https://web.archive.org/web/20140914112013/https://www.mup.com.au/items/149038

- Macklin, Robert (2007). Kevin Rudd : The Biography. Camberwell, Vic.: Penguin Books Australia. ISBN 978-0-670-07135-7.

- Marr, David (2010). "Power Trip : The Political Journey of Kevin Rudd". Quarterly Essay. Melbourne: Black Inc. (38). ISBN 978-1-86395-477-8.

- Stuart, Nicholas (2007). Kevin Rudd : An Unauthorised Political Biography. Melbourne: Scribe. ISBN 978-1-921215-58-2.

- Weller, Patrick (2010). Kevin Rudd: The Making of a Prime Minister. Carlton, Vic.: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 978-0-522-85748-1.

وصلات خارجية

- Official website

- Search or browse Hansard for كڤن رد at OpenAustralia.org

- {{TED speaker}} template missing ID and not present in Wikidata.

| برلمان أستراليا | ||

|---|---|---|

| سبقه گرام مكدوگل |

النائب عن گرفث 1998–2013 |

تبعه تري بتلر |

| مناصب سياسية | ||

| سبقه كيم بيزلي |

زعيم المعارضة 2006–2007 |

تبعه برندان نلسون |

| سبقه جون وارد |

رئيس وزراء إستراليا 2007–2010 |

تبعه جوليا گيلارد |

| سبقه ستيفن سميث |

وزير الشئون الخارجية 2010–2012 |

تبعه بوب كار |

| سبقه جوليا گيلارد |

رئيس وزراء أستراليا 2013 |

تبعه توني أبوت |

| مناصب حزبية | ||

| سبقه كيم بيزلي |

زعيم حزب العمال الأسترالي 2006–2010 |

تبعه جوليا گيلارد |

| سبقه جوليا گيلارد |

زعيم حزب العمال الأستراليا 2013 |

تبعه بيل شورتن |

| مناصب دبلوماسية | ||

| سبقه جوليا گيلارد |

زعيم كومنولث الأمم 2013 |

تبعه توني أبوت |

- Articles with dead external links from March 2020

- Articles with dead external links from September 2010

- Short description with empty Wikidata description

- مواليد 21 سبتمبر

- مواليد 1957

- سنة الميلاد مختلفة في ويكي بيانات

- شهر الميلاد مختلف في ويكي بيانات

- يوم الميلاد مختلف في ويكي بيانات

- Pages using infobox officeholder with unknown parameters

- Articles containing simplified Chinese-language text

- Articles containing traditional Chinese-language text

- مقالات بالمعرفة بحاجة لذكر رقم الصفحة بالمصدر from January 2022

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- TED speaker template missing ID and not in Wikidata

- أشخاص أحياء

- Ambassadors of Australia to the United States

- مستشارو تشاتم هاوس

- أنگليكانيون أستراليون

- دبلوماسيون أستراليون

- أعضاء برلمان أستراليا من حزب العمال الأسترالي

- سياسيون اليمين العمالي

- زعماء معارضة أستراليون

- وزراء شئون خارجية أستراليا

- خريجو الجامعة الوطنية الأسترالية

- أستراليون من أصل إنگليزي

- أستراليون من أصل أيرلندي

- جمهوريون أستراليون

- Commonwealth Chairpersons-in-Office

- متحولون من الكاثوليكية إلى الأنگليكانية

- زعماء حزب العمال الأسترالي

- أعضاء مجلس النواب الأسترالي

- أعضاء مجلس النواب الأسترالي من گريفيث

- أعضاء مجلس وزراء أستراليا

- أشخاص من نامبور، كوينزلاند

- رؤساء وزراء أستراليا

- حكومة رد

- سياسيون أستراليون في القرن 21

- سياسيون أستراليون في القرن 20