أوروبيوم

| |||||||||||||||

| Europium | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| المظهر | silvery white, with a pale yellow tint;[1] but rarely seen without oxide discoloration | ||||||||||||||

| الوزن الذري العياري Ar°(Eu) | |||||||||||||||

| Europium في الجدول الدوري | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| الرقم الذري (Z) | 63 | ||||||||||||||

| المجموعة | n/a | ||||||||||||||

| الدورة | period 6 | ||||||||||||||

| المستوى الفرعي | f-block | ||||||||||||||

| التوزيع الإلكتروني | [Xe] 4f7 6s2 | ||||||||||||||

| الإلكترونات بالغلاف | 2, 8, 18, 25, 8, 2 | ||||||||||||||

| الخصائص الطبيعية | |||||||||||||||

| الطور at د.ح.ض.ق | solid | ||||||||||||||

| نقطة الانصهار | 1099 K (826 °س، 1519 °F) | ||||||||||||||

| نقطة الغليان | 1802 K (1529 °س، 2784 °ف) | ||||||||||||||

| الكثافة (بالقرب من د.ح.غ.) | 5.244 ج/سم³ | ||||||||||||||

| حين يكون سائلاً (عند ن.إ.) | 5.13 ج/سم³ | ||||||||||||||

| حرارة الانصهار | 9.21 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||

| حرارة التبخر | 176 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||

| السعة الحرارية المولية | 27.66 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||

ضغط البخار

| |||||||||||||||

| الخصائص الذرية | |||||||||||||||

| الكهرسلبية | مقياس پاولنگ: 1.2 | ||||||||||||||

| طاقات التأين |

| ||||||||||||||

| نصف القطر الذري | empirical: 180 pm | ||||||||||||||

| نصف قطر التكافؤ | 198±6 pm | ||||||||||||||

| خصائص أخرى | |||||||||||||||

| البنية البلورية | body-centered cubic (bcc) | ||||||||||||||

| سرعة الصوت قضيب رفيع | est. 13.9 W/(m·K) | ||||||||||||||

| التمدد الحراري | poly: 35.0 µm/(m⋅K) (at r.t.) | ||||||||||||||

| المقاومة الكهربائية | poly: 0.900 µΩ⋅m (at r.t.) | ||||||||||||||

| الترتيب المغناطيسي | paramagnetic[2] | ||||||||||||||

| القابلية المغناطيسية | +34000.0×10−6 cm3/mol[3] | ||||||||||||||

| معامل يونگ | 18.2 GPa | ||||||||||||||

| معامل القص | 7.9 GPa | ||||||||||||||

| معاير الحجم | 8.3 GPa | ||||||||||||||

| نسبة پواسون | 0.152 | ||||||||||||||

| صلادة ڤيكرز | 165–200 MPa | ||||||||||||||

| رقم كاس | 7440-53-1 | ||||||||||||||

| التاريخ | |||||||||||||||

| التسمية | after Europe | ||||||||||||||

| الاكتشاف وأول عزل | Eugène-Anatole Demarçay (1896, 1901) | ||||||||||||||

| نظائر الeuropium | |||||||||||||||

| قالب:جدول نظائر europium غير موجود | |||||||||||||||

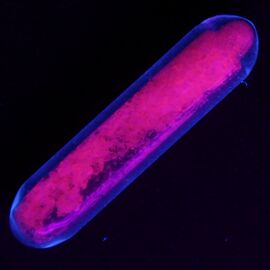

يروپيوم أو أوروپيوم أو اليوروپيوم Europium هو عنصر كيميائي رمزه Eu ورقمه الذري 63. وسـُمي على اسم قارة اوروپا. It is a silvery-white metal of the lanthanide series that reacts readily with air to form a dark oxide coating. Europium is the most chemically reactive, least dense, and softest of the lanthanides. It is soft enough to be cut with a knife. Europium was discovered in 1896, provisionally designated as Σ; in 1901, it was named after the continent of Europe.[4] Europium usually assumes the oxidation state +3, like other members of the lanthanide series, but compounds having oxidation state +2 are also common. All europium compounds with oxidation state +2 are slightly reducing. Europium has no significant biological role but is relatively non-toxic compared to other heavy metals. Most applications of europium exploit the phosphorescence of europium compounds. Europium is one of the rarest of the rare-earth elements on Earth.[5]

أصل الاسم

مكتشف العنصر، أوجين-أناتول ديمارساي، سمّاه على اسم قارة أوروپا.[4]

الخصائص الطبيعية

الأوروبيوم هو فلز مطيل بصلادة مماثلة للرصاص. ويتبلور في شبكة مكعبة موسطنة حول الجسم.[6] ومن بين اللانثانيدات، فإن الأوروبيوم مع الإيتربيوم لديهما أكبر حجم لمول الفلز. وتقترح القياسات المغناطيسية أن ذلك هو نتيجة لكون تلك الفلزات فعلياً ثنائية التكافؤ بينما اللانثانيدات الأخرى هم فلزات ثلاثية التكافؤ.[6]

الأوروپيوم هو أكثر العناصر الأرضية النادرة تفاعلاً؛ فهو يتأكسد بسرعة في الهواء، ويشبه الكالسيوم في تفاعله مع الماء؛ وشحنات العنصر الفلزي في صيغة صلبة، حتى عند تغطيتها بطبقة واقية من الزيت المعدني، فهي نادراً ما تكون براقة. ويشتعل الاوروپيوم في الهواء عند درجة حرارة 150 °م إلى 180 °م.

الخصائص الكيميائية

The chemistry of europium is broadly lanthanoid chemistry, but Europium is the most reactive lanthanoid.[6] It rapidly oxidizes in air, so that bulk oxidation of a centimeter-sized sample occurs within several days.[7] Its reactivity with water is comparable to that of calcium, and the reaction is

- 2 Eu + 6 H

2O → 2 Eu(OH)

3 + 3 H

2

Because of the high reactivity, samples of solid europium rarely have the shiny appearance of the fresh metal, even when coated with a protective layer of mineral oil. Europium ignites in air at 150 to 180 °C to form europium(III) oxide:[8]

- 4 Eu + 3 O

2 → 2 Eu

2O

3

Europium dissolves readily in dilute sulfuric acid to form pale pink[9] solutions of [Eu(H

2O)

9]3+:

- 2 Eu + 3 H

2SO

4 + 18 H

2O → 2 [Eu(H

2O)

9]3+ + 3 SO2−

4 + 3 H

2

Eu(II) vs. Eu(III)

Although usually trivalent, europium readily forms divalent compounds. This behavior is unusual for most lanthanides, which almost exclusively form compounds with an oxidation state of +3. The +2 state has an electron configuration 4f7 because the half-filled f-shell provides more stability. In terms of size and coordination number, europium(II) and barium(II) are similar. The sulfates of both barium and europium(II) are also highly insoluble in water.[10] Divalent europium is a mild reducing agent, oxidizing in air to form Eu(III) compounds. In anaerobic, and particularly geothermal conditions, the divalent form is sufficiently stable that it tends to be incorporated into minerals of calcium and the other alkaline earths. This ion-exchange process is the basis of the "negative europium anomaly", the low europium content in many lanthanide minerals such as monazite, relative to the chondritic abundance. Bastnäsite tends to show less of a negative europium anomaly than does monazite, and hence is the major source of europium today. The development of easy methods to separate divalent europium from the other (trivalent) lanthanides made europium accessible even when present in low concentration, as it usually is.[11]

المركبات

Europium compounds tend to exist in a trivalent oxidation state under most conditions. Commonly these compounds feature Eu(III) bound by 6–9 oxygenic ligands. The Eu(III) sulfates, nitrates and chlorides are soluble in water or polar organic solvents. Lipophilic europium complexes often feature acetylacetonate-like ligands, such as EuFOD.

الهاليدات

Europium metal reacts with all the halogens:

- 2 Eu + 3 X2 → 2 EuX3 (X = F, Cl, Br, I)

This route gives white europium(III) fluoride (EuF3), yellow europium(III) chloride (EuCl3), gray[12] europium(III) bromide (EuBr3), and colorless europium(III) iodide (EuI3). Europium also forms the corresponding dihalides: yellow-green europium(II) fluoride (EuF2), colorless europium(II) chloride (EuCl2) (although it has a bright blue fluorescence under UV light),[13] colorless europium(II) bromide (EuBr2), and green europium(II) iodide (EuI2).[6]

الكالكوجينيات والپنيكتوجينات

Europium forms stable compounds with all of the chalcogens, but the heavier chalcogens (S, Se, and Te) stabilize the lower oxidation state. Three oxides are known: europium(II) oxide (EuO), europium(III) oxide (Eu2O3), and the mixed-valence oxide Eu3O4, consisting of both Eu(II) and Eu(III). Otherwise, the main chalcogenides are europium(II) sulfide (EuS), europium(II) selenide (EuSe) and europium(II) telluride (EuTe): all three of these are black solids. Europium(II) sulfide is prepared by sulfiding the oxide at temperatures sufficiently high to decompose the Eu2O3:[14]

- Eu2O3 + 3 H2S → 2 EuS + 3 H2O + S

The main nitride of europium is europium(III) nitride (EuN).

النظائر

Naturally occurring europium is composed of two isotopes, 151Eu and 153Eu, which occur in almost equal proportions; 153Eu is slightly more abundant (52.2% natural abundance). While 153Eu is stable, 151Eu was found to be unstable to alpha decay with a half-life of 4.6×1018 years,[15] giving about one alpha decay per two minutes in every kilogram of natural europium. Besides the natural radioisotope 151Eu, 39 artificial radioisotopes have been characterized from 130Eu to 170Eu,[16][17] the most stable being 150Eu with a half-life of 36.9 years, 152Eu with a half-life of 13.516 years, 154Eu with a half-life of 8.592 years, and 155Eu with a half-life of 4.742 years. All the others have half-lives shorter than 100 days, with the majority shorter than 3 minutes.

This element also has 27 meta states, with the most stable being 150mEu (12.8 hours), 152m1Eu (9.3116 hours) and 152m5Eu (96 minutes).[16] The primary decay mode for isotopes lighter than 153Eu is electron capture to samarium isotopes, and the primary mode for heavier isotopes is beta minus decay to gadolinium isotopes.

الأوروپيوم كناتج عن الانشطار النووي

| Prop: Unit: |

t½ a |

Yield % |

Q * keV |

βγ * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 155Eu | 4.76 | .0803 | 252 | βγ |

| 85Kr | 10.76 | .2180 | 687 | βγ |

| 113mCd | 14.1 | .0008 | 316 | β |

| 90Sr | 28.9 | 4.505 | 2826 | β |

| 137Cs | 30.23 | 6.337 | 1176 | βγ |

| 121mSn | 43.9 | .00005 | 390 | βγ |

| 151Sm | 96.6 | .5314 | 77 | β |

Europium is produced by nuclear fission: 155Eu (half-life 4.742 years) has a fission yield of 0.033% for uranium-235 with thermal neutrons.[18] The fission product yields of europium isotopes are low, as they are near the top of the mass range of fission products.

As with other lanthanides, many isotopes of europium have high cross sections for neutron capture, often high enough to be neutron poisons.[بحاجة لمصدر]

| النظير | 151Eu | 152Eu | 153Eu | 154Eu | 155Eu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield | ~10 | low | 1580 | >2.5 | 330 |

| Barns | 5900 | 12800 | 312 | 1340 | 3950 |

151Eu is the beta decay product of samarium-151 (not included in above yield), but since this has a long decay half-life and short mean time to neutron absorption, most 151Sm instead ends up as 152Sm.

152Eu (half-life 13.517 years) and 154Eu (half-life 8.592 years) cannot be beta decay products because 152Sm and 154Sm are non-radioactive, but 154Eu is the only long-lived "shielded" nuclide, other than 134Cs, to have a fission yield of more than 2.5 parts per million fissions.[19] A larger amount of 154Eu is produced by neutron activation of a significant portion of the non-radioactive 153Eu; however, as shown by the cross-sections, much of this is further converted to 155Eu and 156Eu, ending up as gadolinium.

الاستخدامات

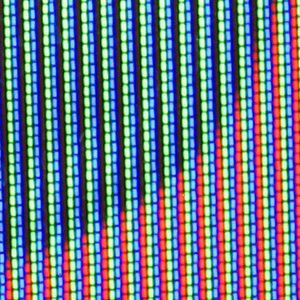

هناك القليل من الاستخدامات التجارية لفلز الأوروپيوم, إلا أنه قد استـُعمل to لتطعيم بعض أنواع الزجاج لصناعة ليزرات، كما يـُستخدم في الكشف عن متلازمة داون وبعض الأمراض الجينية الأخرى. وبسبب قدرته على امتصاص النيوترونات, فيجري دراسة استخدامه في المفاعلات النووية. اكسيد الأوروپيوم (Eu2O3) يـُستعمل على نطاق واسع كفوسفور أحمر في أجهزة التلفزيون و مصابيح الفلوسنت, وكمنشط للفوسفورات المصنوعة من الإتريوم. وبينما الاوروپيوم ثلاثي التكافؤ يعطي فوسفورات حمراء, فالاوروپيوم ثنائي التكافؤ يعطي فوسفورات زرقاء. مجموعتا فوسفور الاوروبيوم, مجموعتان مع فوسفورات التربيوم الصفراء/الخضراء, يعطون أضواءً "ثلاثية الألوان trichromatic" وهي التي أصبحت هامة جداً للحصول على إضاءة اقتصادية. ويـُستخدم أيضاً كعامل في صناعة زجاج الفلورسنت. ويستخدم استشعاع الاوروپيوم لفحص التفاعلات الجزيئية الحيوية في غرابيل اكتشاف العقاقير. ويستخدم كذلك في فوسفورات مكافحة التزوير في الأوراق النقدية لليورو. [20]

ويستخدم الاوروپيوم بنسب ضئيلة جداً في دراسات الكيمياء الأرضية و الپترولوجيا فهم العمليات المكونة للصخور النارية (الصخور التي بردت من magma أو الحمم). وطبيعة europium anomaly found تستخدم للمساعدة في اعادة بناء العلاقات داخل مجموعة من الصخور النارية.

التاريخ

Europium was first found by Paul Émile Lecoq de Boisbaudran in 1890, who obtained basic fraction from samarium-gadolinium concentrates which had spectral lines not accounted for by samarium or gadolinium; however, the discovery of europium is generally credited to French chemist Eugène-Anatole Demarçay, who suspected samples of the recently discovered element samarium were contaminated with an unknown element in 1896 and who was able to isolate europium in 1901. When the europium-doped yttrium orthovanadate red phosphor was discovered in the early 1960s, and understood to be about to cause a revolution in the color television industry, there was a mad scramble for the limited supply of europium on hand among the monazite processors. (Typical europium content in monazite was about 0.05%.) Luckily, Molycorp, with its bastnäsite deposit at Mountain Pass California, whose lanthanides had an unusually "rich" europium content of 0.1%, was about to come on-line and provide sufficient europium to sustain the industry. Prior to europium, the color-TV red phosphor was very weak, and the other phosphor colors had to be muted, to maintain color balance. With the brilliant red europium phosphor, it was no longer necessary to mute the other colors, and a much brighter color TV picture was the result. Europium has continued in use in the TV industry ever since, and, of course, also in computer monitors. California bastnäsite now faces stiff competition from Bayan Obo, China, with an even "richer" europium content of 0.2%. Frank Spedding, celebrated for his development of the ion-exchange technology that revolutionized the rare earth industry in the mid-1950s once related the story of how, in the 1930s, he was lecturing on the rare earths when an elderly gentleman approached him with an offer of a gift of several pounds of europium oxide. This was an unheard-of quantity at the time, and Spedding did not take the man seriously. However, a package duly arrived in the mail, containing several pounds of genuine europium oxide. The elderly gentleman had turned out to be the Dr. McCoy who had developed a famous method of europium purification involving redox chemistry.

التواجد

لا يتواجد الأوروپيوم في الطبيعة كعنصر حر؛ إلا أن هناك العديد من المعادن التي تحتوي على الأوروپيوم, وأهم المصادر هي باستناسيت و مونازيت وxenotime and loparite-(Ce).[21]

Depletion or enrichment of europium in minerals relative to other rare-earth elements is known as the europium anomaly.[22] Europium is commonly included in trace element studies in geochemistry and petrology to understand the processes that form igneous rocks (rocks that cooled from magma or lava). The nature of the europium anomaly found helps reconstruct the relationships within a suite of igneous rocks. The median crustal abundance of europium is 2 ppm; values of the less abundant elements may vary with location by several orders of magnitude.[23]

الاوروپيوم ثنائي التكافؤ بكميات صغيرة وُجد أنه المنشط للاستشعاع fluorescence الأزرق الساطع لبعض العينات من فلوريتات المعادن (ثنائي فلوريد الكالسيوم CaF2). The reduction from Eu3+ to Eu2+ is induced by irradiation with energetic particles.[24] The most outstanding examples of this originated around Weardale and adjacent parts of northern England; it was the fluorite found here that fluorescence was named after in 1852, although it was not until much later that europium was determined to be the cause.[25][26][27][28]

In astrophysics, the signature of europium in stellar spectra can be used to classify stars and inform theories of how or where a particular star was born. For instance, astronomers used the relative levels of europium to iron within the star LAMOST J112456.61+453531.3 to propose that the accretion process for the star occurred late.[29]

النظائر

مقالة مفصلة: نظائر الاوروپيوم

مقالة مفصلة: نظائر الاوروپيوم

Naturally occurring europium is composed of 2 isotopes, 151Eu and 153Eu, with 153Eu being the most abundant (52.2% natural abundance). While 153Eu is stable, 151Eu was recently found to be unstable to alpha decay with half-life of yr[30], in reasonable agreement with theoretical predictions. Besides natural radioisotope 151Eu, 35 artificial radioisotopes have been characterized, with the most stable being 150Eu with a half-life of 36.9 years, 152Eu with a half-life of 13.516 years, and 154Eu with a half-life of 8.593 years. All of the remaining radioactive isotopes have half-lives that are less than 4.7612 years, and the majority of these have half-lives that are less than 12.2 seconds. This element also has 8 meta states, with the most stable being 150mEu (t½ 12.8 hours), 152m1Eu (t½ 9.3116 hours) and 152m2Eu (t½ 96 minutes).

The primary decay mode before the most abundant stable isotope, 153Eu, is electron capture, and the primary mode after is beta minus decay. The primary decay products before 153Eu are isotopes of samarium (Sm) and the primary products after are isotopes of gadolinium (Gd).

المحاذير

سمية مركبات الاوروپيوم لم تـُدرس بالكامل بعد, but there are no clear indications that europium is highly toxic compared to other heavy metals. The metal dust presents a fire and explosion hazard. Europium has no known biological role.

عزل الاوروپيوم

Europium metal is available commercially so it is not normally necessary to make it in the laboratory, which is just as well as it is difficult to isolate as the pure metal. This is largely because of the way it is found in nature. The lanthanoids are found in nature in a number of minerals. The most important are xenotime, monazite, and bastnaesite. The first two are orthophosphate minerals LnPO4 (Ln denotes a mixture of all the lanthanoids except promethium which is vanishingly rare) and the third is a fluoride carbonate LnCO3F. Lanthanoids with even atomic numbers are more common. The most common lanthanoids in these minerals are, in order, cerium, lanthanum, neodymium, and praseodymium. Monazite also contains thorium and yttrium which makes handling difficult since thorium and its decomposition products are radioactive.

For many purposes it is not particularly necessary to separate the metals, but if separation into individual metals is required, the process is complex. Initially, the metals are extracted as salts from the ores by extraction with sulfuric acid (H2SO4), hydrochloric acid (HCl), and sodium hydroxide (NaOH). Modern purification techniques for these lanthanoid salt mixtures are ingenious and involve selective complexation techniques, solvent extractions, and ion exchange chromatography.

Pure europium is available through the electrolysis of a mixture of molten EuCl3 and NaCl (or CaCl2) in a graphite cell which acts as cathode using graphite as anode. The other product is chlorine gas.

هامش

- ^ Greenwood, N. N. (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd Edition ed.). Oxford:Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-3365-4.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). "Magnetic susceptibility of the elements and inorganic compounds". CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (PDF) (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- ^ Weast, Robert (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, Florida: Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. pp. E110. ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- ^ أ ب "Periodic Table: Europium". Royal Society of Chemistry.

- ^ Stwertka, Albert. A Guide to the Elements, Oxford University Press, 1996, p. 156. ISBN 0-19-508083-1

- ^ أ ب ت ث Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, E. "Inorganic Chemistry" Academic Press: San Diego, 2001. ISBN 0-12-352651-5.

- ^ Hamric, David (November 2007). "Rare-Earth Metal Long Term Air Exposure Test". elementsales.com. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ Ugale, Akhilesh; Kalyani, Thejo N.; Dhoble, Sanjay J. (2018). "Potential of europium and samarium β -diketonates as red light emitters in organic light-emitting diodes". Lanthanide-Based Multifunctional Materials. pp. 59–97. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-813840-3.00002-8. ISBN 978-0-12-813840-3.

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 1243. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Cooley, Robert A.; Yost, Don M.; Stone, Hosmer W. (2006) [1946]. "Europium(II) Salts". Inorganic Syntheses. Vol. 2. pp. 69–73. doi:10.1002/9780470132333.ch19. ISBN 978-0-470-13233-3.

- ^ McGill, Ian. "Rare Earth Elements". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Vol. 31. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. p. 199. doi:10.1002/14356007.a22_607.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|authors=(help). - ^ Phillips, Sidney L.; Perry, Dale L. (1995). Handbook of inorganic compounds. Boca Raton: CRC Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-8493-8671-8.

- ^ Howell, J.K.; Pytlewski, L.L. (August 1969). "Synthesis of divalent europium and ytterbium halides in liquid ammonia". Journal of the Less Common Metals. 18 (4): 437–439. doi:10.1016/0022-5088(69)90017-4.

- ^ Archer, R. D.; Mitchell, W. N.; Mazelsky, R. (1967). "Europium (II) Sulfide". Inorganic Syntheses. Vol. 10. pp. 77–79. doi:10.1002/9780470132418.ch15. ISBN 978-0-470-13241-8.

- ^ Casali, N.; Nagorny, S. S.; Orio, F.; Pattavina, L.; et al. (2014). "Discovery of the 151Eu α decay". Journal of Physics G: Nuclear and Particle Physics. 41 (7) 075101. arXiv:1311.2834. Bibcode:2014JPhG...41g5101C. doi:10.1088/0954-3899/41/7/075101. S2CID 116920467.

- ^ أ ب Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S.; Audi, G. (2021). "The NUBASE2020 evaluation of nuclear properties" (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 45 (3): 030001. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/abddae.

- ^ Kiss, G. G.; Vitéz-Sveiczer, A.; Saito, Y.; et al. (2022). "Measuring the β-decay properties of neutron-rich exotic Pm, Sm, Eu, and Gd isotopes to constrain the nucleosynthesis yields in the rare-earth region". The Astrophysical Journal. 936 (107): 107. Bibcode:2022ApJ...936..107K. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ac80fc. hdl:2117/375253. S2CID 252108123.

- ^ Aarkrog, A.; Lippert, J. (28 July 1967). "Europium-155 in Debris from Nuclear Weapons". Science. 157 (3787): 425–427. Bibcode:1967Sci...157..425A. doi:10.1126/science.157.3787.425. PMID 6028023.

- ^ Tables of Nuclear Data, Japan Atomic Energy Agency Archived يونيو 10, 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Europium and the Euro [1]

- ^ Bünzli, Jean-Claude G. (2013). "Lanthanides". Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. pp. 1–43. doi:10.1002/0471238961.1201142019010215.a01.pub3. ISBN 978-0-471-48494-3.

- ^ Sinha, Shyama P.; Scientific Affairs Division, North Atlantic Treaty Organization (1983). "The Europium anomaly". Systematics and the properties of the lanthanides. Springer. pp. 550–553. ISBN 978-90-277-1613-2.

- ^ ABUNDANCE OF ELEMENTS IN THE EARTH'S CRUST AND IN THE SEA, CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 97th edition (2016–2017), p. 14-17

- ^ Bill, H.; Calas, G. (1978). "Color centers, associated rare-earth ions and the origin of coloration in natural fluorites". Physics and Chemistry of Minerals. 3 (2): 117–131. Bibcode:1978PCM.....3..117B. doi:10.1007/BF00308116. S2CID 93952343.

- ^ Allen, Robert D. (1952). "Variations in chemical and physical properties of fluorite" (PDF). Am. Mineral. 37: 910–30.

- ^ Valeur, Bernard; Berberan-Santos, Mário N. (June 2011). "A Brief History of Fluorescence and Phosphorescence before the Emergence of Quantum Theory". Journal of Chemical Education. 88 (6): 731–738. Bibcode:2011JChEd..88..731V. doi:10.1021/ed100182h.

- ^ Mariano, A.N; King, P.J (May 1975). "Europium-activated cathodoluminescence in minerals". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 39 (5): 649–660. Bibcode:1975GeCoA..39..649M. doi:10.1016/0016-7037(75)90008-3.

- ^ Przibram, K. (January 1935). "Fluorescence of Fluorite and the Bivalent Europium Ion". Nature. 135 (3403): 100. Bibcode:1935Natur.135..100P. doi:10.1038/135100a0.

- ^ Xing, Qian-Fan; Zhao, Gang; Aoki, Wako; Honda, Satoshi; Li, Hai-Ning; Ishigaki, Miho N.; Matsuno, Tadafumi (29 April 2019). "Evidence for the accretion origin of halo stars with an extreme r-process enhancement". Nature. 3 (7): 631–635. arXiv:1905.04141. Bibcode:2019NatAs...3..631X. doi:10.1038/s41550-019-0764-5. S2CID 150373875.

- ^ Search for α decay of natural Europium, P. Belli, R. Bernabei, F. Cappell, R. Cerulli, C.J. Dai, F.A. Danevich, A. d'Angelo, A. Incicchitti, V.V. Kobychev, S.S. Nagorny, S. Nisi, F. Nozzoli, D. Prosperi, V.I. Tretyak, and S.S. Yurchenko, Nucl. Phys. A 789, 15 (2007) DOI:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2007.03.001

المصادر

وصلات خارجية

| الجدول الدوري | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | He | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Li | Be | B | C | N | O | F | Ne | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Na | Mg | Al | Si | P | S | Cl | Ar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| K | Ca | Sc | Ti | V | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | Ge | As | Se | Br | Kr | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rb | Sr | Y | Zr | Nb | Mo | Tc | Ru | Rh | Pd | Ag | Cd | In | Sn | Sb | Te | I | Xe | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cs | Ba | La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Pm | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | Lu | Hf | Ta | W | Re | Os | Ir | Pt | Au | Hg | Tl | Pb | Bi | Po | At | Rn | ||||||||||

| Fr | Ra | Ac | Th | Pa | U | Np | Pu | Am | Cm | Bk | Cf | Es | Fm | Md | No | Lr | Rf | Db | Sg | Bh | Hs | Mt | Ds | Rg | Uub | Uut | Uuq | Uup | Uuh | Uus | Uuo | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||